March 2020 Newsletter

Welcome to the March 2020 issue of the Global Washington newsletter.

IN THIS ISSUE

Letter from our Executive Director

To honor International Women’s Day, Global Washington has launched a month-long issue campaign to elevate the importance of ending gender-based violence. This month we are also celebrating the 25th anniversary of an historic gathering in Beijing that was a threshold moment for women’s rights – the Beijing Declaration, which set out specific goals to end violence against women globally.

Despite the tremendous progress that has been made since the Beijing Declaration, we still have a long way to go. The World Health Organization estimates that globally more than one in three women has experienced physical and/or sexual violence in her lifetime.

Today, numerous Global Washington members are part of a global movement to end gender-based violence. And it does feel like a movement. Some of the changes are happening at the grassroots community level, while others are focused on shifting national and international policy.

Please take the time to learn about the effective strategies that GlobalWA members are using to end gender-based violence around the world. In the articles below, we take an in-depth look at how the global network of Vital Voices elevates women leaders around the world to effect positive change. You will also find out how this month’s Goalmaker, Amanda Klasing from Human Rights Watch, became involved with the global women’s rights movement. And finally, I hope you will take the time to watch a video interview with Rikki Nathanson, a pioneering transgender activist from Zimbabwe, who is on the board of OutRight Action International.

Also this month, we have decided to host an event that will be online only to support social distancing in light of the Coronavirus in Washington state. Please join on March 18 for a virtual event on this topic. We will have speakers representing OutRight Action International, Rise Beyond the Reef, Seattle International Foundation, and CARE.

I hope you are staying healthy, and I also encourage you to stay connected online to the GlobalWA community.

Kristen Dailey

Executive Director

Back to Top

Issue Brief

Strategies for Ending Gender-based Violence Globally

By Joanne Lu

A workshop in NYC, led by Panmela Castro, a graffiti artist who was a victim of domestic violence. Vital Voices connected her with other graffiti artists and helped her establish Artefeito, an organization that uses art to transform culture for social progress. Photo courtesy of Vital Voices Global Partnership.

Twenty-five years ago, tens of thousands of women from around the world decided it was beyond time for women to have a seat at the table of their own wellbeing and advancement. On September 4, 1995, they traveled to Beijing, China to attend the U.N.’s Fourth World Conference on Women, a critical event that would later be recognized as a significant turning point for the global agenda for gender equality.

It was at that conference that then-First Lady of the United States Hilary Clinton delivered a famous speech in which she declared that, “human rights are women’s rights, and women’s rights are human rights.” Also at that meeting, 189 countries unanimously agreed to adopt an agenda that set out to achieve gender equality in 12 critical areas, including violence against women. Sixty-eight countries even made actionable commitments, such as a six-year, $1.5 billion program by the U.S. to fight domestic violence. Perhaps most importantly, some experts say the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action made violence against women a matter for public discussion, instead of just a private, family issue.

Although the Beijing Declaration continues to be celebrated as a major step forward for women, no country has achieved equality yet, and violence against women and girls, in particular, remains an alarming global problem.

Femicide Watch reports that in 2017, an estimated 87,000 women around the world were murdered – more than half of them (50,000) by an intimate partner or family member. This means that every single day, 137 women are being killed by their own family.

The World Health Organization (WHO) also estimates that more than one in three women have experienced physical and/or sexual intimate-partner violence or sexual violence by a non-partner in their lifetime. But the estimates vary by region and in some countries, intimate-partner violence has affected up to 70 percent of women.

It’s true that gender-based violence (GBV) includes more than just domestic violence against women. CARE defines GBV as “a harmful act or threat based on a person’s sex or gender identity.” So, it certainly includes violence against men and boys, such as the targeted killing of men and boys in conflict or sexual violence against male refugees. However, GBV does disproportionately affect women, girls and other minorities (particularly LGBTIQ people), largely because they are disempowered by systemic gender inequality. And it can take on many different forms, including street harassment, human trafficking, female genital mutilation, child marriage, marital rape, honor killings, psychological bullying, and cyber harassment.

What’s more, GBV has serious repercussions on survivors. For example, the WHO found that women who have experienced intimate-partner violence report higher rates of depression, having an abortion and contracting HIV than women who have not. Many survivors also face social stigma.

Since the Beijing conference in 1995, governments, NGOs and intergovernmental organizations have adopted many strategies to fight gender-based violence and bring it to an end globally, all of which must work together to change societies that allow gender-based violence to continue.

To tackle a problem, one must first understand the scale and scope of the problem. But GBV is notoriously under-reported because of barriers like social stigma and limited access to services and resources. This lack of data means that it’s nearly impossible to accurately assess if global rates of GBV are increasing or decreasing over time. For this reason, there has been a push to collect more data. Researchers are finding better ways to collect information, like calling violence-against-women surveys “women’s health surveys” instead, and organizations, like Human Rights Watch, are compiling the data into reports for use in advocacy. OutRight Action International, an advocacy group that fights for the rights of LGBTIQ people around the world, also does a lot of work to fill the huge gaps in data regarding violence against sexual and gender minorities.

As a result of improved data collection and public conversations about GBV after Beijing, two-thirds of countries have adopted laws to stop domestic violence. But Every Woman Treaty wants to take it a step further by creating a legally binding global treaty that requires countries to prevent and address violence against women and girls. In the meantime, organizations like OutRight and Vital Voices are working with institutions on the ground to make sure that the laws are actually being enforced and that women, girls, and LGBTIQ individuals have access to the help and services they need.

But ending GBV is more than just a legal battle; it also requires resources, including financing. Although funding for gender equality and women’s empowerment is increasing, women’s rights organizations are still “significantly underfunded” compared with other development programs, according to the Equality Institute.

Ending GBV also requires a shift in cultural norms and attitudes toward gender. That’s why Breakthrough is using pop culture, media and technology to challenge gender-based norms in the U.S. and India and to help tackle violence. For example, their first campaign in India in 2008 was a series of TV ads called “Bell Bajao!” (or “Ring the Bell!”), which promoted the idea that violence is everyone’s business. So, if you witness your neighbor being violent toward his wife, you can help by creating an interruption, like ringing their doorbell. Breakthrough is also helping women in India realize for themselves that violence against them by their husbands is, in fact, a problem and should not be accepted.

To accelerate changes from the ground up, some organizations are focused on supporting grassroots activists. For example, the Seattle International Foundation (SIF) has been partnering with the U.S. Department of State for years on a program called Mujeres Adelante (or “Women Forward” in Spanish), which addresses GBV by hosting grassroots women leaders from Central America in the U.S. for two weeks of leadership training and exchanges. The goal, according to SIF, is to create a more organized and powerful network of change agents across the region who can support each other in their efforts to end GBV.

While women become more empowered to assert their rights, many organizations are also realizing the importance of engaging men and boys in the conversation in order to break the cycle of violence. After all, violence in many cases is learned behavior. In Lebanon, for example, a study found that men who had witnessed their fathers beating their mothers during childhood were three times more likely to perpetrate physical violence. However, CARE is helping men and boys redefine masculinity through family economic initiatives that teach couples how to run their households as equals, through male support groups that have open discussions about GBV and by facilitating conversations about GBV between male change agents and political and religious leaders. In patriarchal systems, it’s especially important for men to lead other men by example. That’s why Vital Voices, an organization that invests in women leaders, puts a big emphasis on male allies when they train police officers, lawyers, judges, and religious leaders – professions still dominated by men in many countries – on how to prevent and respond to violence against women.

Although there’s still a long road ahead in the fight to end GBV, experts are encouraged that at the very least, social change has been initiated. And as all of these strategies continue to work together to address the many facets of violence, changemakers are optimistic that the momentum will build: new generations of girls will grow up knowing that they have a right to safety, education, and decision-making about their own wellbeing, and new generations of boys will learn how to be allies. But making that a reality will require sustained efforts to actively change norms and uphold the rights of women, girls, and minorities everywhere.

***

The following Global Washington members are working to end gender-based violence around the world:

Awamaki

Awamaki partners with women’s artisan cooperatives to teach them to start and run their own businesses. Awamaki invests in women’s skills, connects them to markets and supports their empowerment. Through Awamaki’s programs, artisan women from marginalized and remote villages learn business and leadership skills so they can earn an income and gain a voice in their households and their communities. The organization’s trainings include gender-based violence awareness and women’s rights topics, and its income-generating programs allow women to build successful futures and create a better life for themselves and their children.

Every Woman Treaty

Every Woman Treaty is a coalition of more than 1,700 women’s rights activists, including 840 organizations, in 128 nations working to advance a global binding norm on the elimination of violence against women and girls. The organization’s working group studied recommendations from the United Nations, the World Health Organization, and scholarly research on how to solve the problem of violence against women and girls, including trafficking and modern slavery, and found that a global treaty is the most powerful step the international community can take to address an issue of this magnitude.

Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) fights to end violence against women and girls, advance women’s right to health care, and promote women’s economic and social rights. HRW’s method is straightforward. The organization investigates violations of women’s rights, talking to the women and girls directly affected on the ground in countries around the world. HRW documents its findings in hard-hitting reports with detailed recommendations. Then HRW uses these reports—and targeted media outreach—to generate pressure for reform by the entities that perpetrate abuses against women. All HRW’s work is intersectional and is done in partnership with local organizations and activists. HRW researchers fight sexual harassment in the workplace and abuses in garment manufacturing to combatting human trafficking; work to end child marriage, and defending women’s access to land and the right to health, including sexual and reproductive health. HRW’s latest work is uncovering the new intersections between technology and gender-based violence, including digital stalking and on-line harassment, as it continues to document abuses and foster coalitions that protect, defend, and fight for women’s rights around the world.

Kati Collective

Kati Collective improves systems across global development by providing experienced, strategic, and pragmatic action focused on three of the most important drivers of change: women, digital, and partnerships. In all of its engagements, Kati Collective applies a gender lens, thinking strategically about how to engage men and boys, while concurrently supporting women and girls in LMICs. Kati Collective’s work concentrates on culturally relevant technology for social impact, focusing on girls’ and women’s empowerment applications for effectively educating communities and maximizing outcomes for the underserved across the globe. Gender-based violence, which is faced by women globally, is not a female problem – it is a human problem, rooted in the attitudes, cultural norms, and behaviors of men worldwide. When men and boys are educated about ingrained sexist and systemic biases, they begin to see how they can partner in stopping these behaviors and practices from harming the next generation. Kati Collective approaches partnerships with the goal of aligning agendas regarding GBV and other female-centric issues forward collectively. Local and global perspectives must come together for impactful and lasting systemic change. Kati Collective provides its clients with perspective and experience, as well as the strategies and tools needed to improve outcomes for women on a global scale.

Landesa

Landesa champions and works to secure land rights for millions of those living in poverty worldwide, primarily rural women and men, to promote social justice and provide opportunity. Evidence shows that women’s land rights can transform power dynamics within households and communities, improving women’s status and their own perceptions of their power. This empowerment forms the bedrock for greater economic opportunity for women, and can also contribute to better health outcomes, including potential reductions in gender-based violence, rates of HIV infection, and other threats to women’s safety. In West Bengal, India, Landesa is working with USAID and PepsiCo to raise awareness of issues related to GBV in agricultural supply chains. This work includes developing guidance documents for a project that is helping women farmers learn skills to participate in PepsiCo’s potato supply chain. Guidance has been tailored both for field staff who work directly with farmers and for management staff, including training materials developed in collaboration with a local CSO to help field staff address GBV. Across more than 50 countries, Landesa has helped strengthen land rights for more than 180 million families.

Mercy Corps

Mercy Corps is a global team of nearly 6,000 humanitarians working in more than 40 countries around the world. From Colombia to the Central African Republic, Mercy Corps partners with local communities to build strong, equitable, and protective societies in which women and girls can thrive. In order to combat Gender-Based Violence (GBV), Mercy Corps works to address the root causes of GBV and connect survivors with the vital resources and services they need. In Lebanon, Mercy Corps hosts a series of dialogue sessions for Syrian refugees in order to bring awareness to GBV and provides case management, connecting survivors to medical and legal services, psychological support and safe housing.

OutRight Action International

Lesbians, bisexual women and transgender (LBT) people around the world often face violence and exclusion in many spheres of their lives, fueled by laws that criminalize same-sex relations and gender non-conformity and encouraged by governments who tolerate, endorse, or directly sponsor the violent clamp-down on those who do not follow prevailing societal norms. Often LBT people are excluded or driven away from needed services and social support, and violence often goes unreported. They are also often denied access to justice based on archaic laws that limit the definition of rape while also delegitimizing same-sex and queer intimacy. OutRight Action International works with grassroots partners in Asia and the Caribbean to ensure that the experiences of LBT people are included in anti-gender-based violence work. For example, in 2019, OutRight and its Caribbean partners launched the Frontline Alliance: Caribbean Partnerships Against Gender Based Violence project to engage first responders, local government officials and others with a focus on domestic violence, family violence and intimate partner violence and to advocate for improvement in policies and protocols through engagement in research, trainings and strategic campaigning. OutRight has also documented the violence and exclusion LBT women face in Asia, worked with grassroots partners to improve domestic violence protections for LGBT people in Sri Lanka and the Philippines, Myanmar and China, and is currently launching a regional platform of experts on SOGIE and GBV in Asia.

Oxfam America

Oxfam America’s work to advance gender justice is multifaceted and tailored to the people Oxfam serves. In some countries, Oxfam is the largest and most prominent organization to take a stand for women and gender-diverse people, and alongside them, often supporting the infrastructures of burgeoning movements. In other countries, like Sri Lanka, Oxfam helps rethink entrenched systems and remap biases to shift attitudes and overcome barriers. In all places, Oxfam strives for sustainable change. Oxfam does so first by acknowledging women, girls, and feminist actors as effective social change agents who must have a hand in ensuring their own rights and in the development they most want to see – development that will transform their families, communities and countries. Oxfam’s gender-based violence (GBV) work is focused on working with women’s rights organizations and feminist movement actors in 30 countries to challenge and transform harmful social norms. Oxfam’s focus on ending GBV is on addressing changes in social norms that perpetrate violence against women in creative ways and engaging feminist activists a youth at the local level. Oxfam’s global, regional, and national GBV work includes: 1) innovative global and national campaigning activities, like the Enough campaign

Working with digital influencers to counter anti-rights actors; 2) engaging and supporting the agendas of women’s rights organizations and feminist movement actors; 3) collaboration with feminist funds to provide small, flexible grants to young feminist organizers running campaigns; and 4) supporting the mobilization of young people at regional level.

Seattle International Foundation

Seattle International Foundation (SIF) champions good governance and equity in Central America through support for rule of law and the strengthening of civil society. When security and rule of law deteriorate in the Northern Triangle of Central America, women face not only systemic violence from powerful gangs, impunity and government repression, but pervasive domestic and sexual violence as well. This has exacerbated the tendency to migrate, despite a high likelihood of facing additional violence en route and a slim likelihood of obtaining asylum in the United States. SIF has committed to addressing and mitigating this reality through its multi-prong approach and through its key initiatives: the Central America Donors Forum, Central America in Washington, D.C., Central America and Mexico Youth (CAMY) Fund, Centroamérica Adelante and the Independent Journalism Fund.

Vista Hermosa

Vista Hermosa is a family foundation located in Pasco WA, established by Ralph and Cheryl Broetje in 1990 to invest in the growth of flourishing communities. Informed by teachings of servant leadership, healing centered engagement and empowered worldview, Vista Hermosa takes a holistic approach to understanding and reconciling people’s connections to self, others, God, and place (shalom). Vista Hermosa accompanies very marginalized groups of people to discover who they are, find their voice, and be the solutions to their own wellbeing and development. The foundation currently funds partners in Mexico, Haiti, India, and East Africa, as well as the U.S. One of its strategies to address gender-based violence is through supporting the adaptation of SASA! (originally developed in Uganda), a community-led awareness, education and action methodology. Vista Hermosa funded the adaptation for the Haitian context and most recently for Mexico/Central America. The foundation is currently assembling a group of funders to support a cohort of regional NGOs to implement this evidence-based curriculum that addresses power imbalances between women and men in communities. Vista Hermosa also supports a range of organizations working on child and sex trafficking, FGM, and new masculinities.

Vital Voices

Vital Voices is a global movement that invests in women leaders solving the world’s greatest challenges. Vital Voices understands that, in order for the world to embrace women’s full potential across industries and issues, gender-based violence (GBV) must be eliminated. Vital Voices works with women leaders and male allies to ensure that victims and survivors of GBV gain better access to services, protection and the justice they deserve. Vital Voices oversees key programs implemented in partnership with local leaders to deliver on this work. The Voices Against Violence Initiative champions innovative solutions to end GBV. Within Voices Against Violence, Vital Voices provides and administers Urgent Assistance Funds to survivors of extreme cases of GBV who do not have alternative means of support for immediate, short-term needs such as medical expenses, psychosocial counseling, emergency shelter and more. Also through Voices Against Violence, Vital Voices hosts Justice Institutes – interactive training programs that promote holistic response to violence and exploitation by convening judges, prosecutors, law enforcement and service providers and other stakeholders across the justice system to focus on victim safety and offender accountability. Vital Voices also oversees the Global Freedom Exchange, which provides a dynamic educational and mentoring experience for emerging and established women leaders who are on the forefront of global efforts to prevent and respond to the destructive crime of human trafficking. These programs support Vital Voices’ work protecting human rights so that everyone can enjoy the safety and security they deserve.

Back to Top

Organization Profile

Vital Voices Invests in Women Leaders, Empowering Them to Turn Their Bold Visions for Change Into Reality

By Joanne Lu

Vital Voices staff and Global Freedom Exchange Fellows from countries across Africa gathered in Cape Town for a “Regional Activation.” Pictured here, the group visited a women-owned, women-run social enterprise, called Khayelitsha Cookie Company. Photo courtesy of Vital Voices Global Partnership.

Alyse Nelson was just a college student when she heard then-First Lady Hilary Clinton’s landmark speech on women’s rights at the UN’s Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995: “If there is one message that echoes forth from this conference, let it be that human rights are women’s rights, and women’s rights are human rights, once and for all.”

Little did she know that the fire that she felt in that moment would forever change her life, setting her on a quest “to use power to empower and to use voice to give voice.”

Just two years after the conference, Nelson worked with several other women, including Clinton, then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and Ambassador Swanee Hunt, to establish the Vital Voices Democracy Initiative, a State Department program which sought to promote women’s advancement as a U.S. foreign policy goal. By 1999, the program was ready to become an independent non-governmental organization, Vital Voices Global Partnership, a network-based organization on a mission to “invest in women leaders who are solving the world’s greatest challenges.” Vital Voices today supports women leaders through a myriad of programs – including fellowships, grants and training – such as individualized investment and activations through their international network to expand leaders’ skills, connections and visibility. Vital Voices works to turn women leaders’ daring vision for change into bold realities.

Today, Nelson is the president and CEO of Vital Voices, now a vast global network of more than 18,000 women leaders (and male allies) in 182 countries and territories. But their resounding impact is far greater as many women leaders are changing the lives of thousands and millions more, says Nicole Hauspurg, Vital Voices’ Director of Justice Initiatives on the Human Rights team. After all, she says, women are multipliers; often demonstrating a unique ability and willingness to pay forward their opportunities in order to have a broader impact on their communities. This attitude is exhibited even in the way that new women leaders connect with Vital Voices. While some women cold-call and others respond to open applications for fellowships or programs, the primary way Vital Voices identifies women leaders is through other women leaders in the network.

Specifically, Vital Voices supports women who are who are creating change in four key ways: they are boosting economic empowerment and entrepreneurship in their communities; they are promoting human rights and ending gender-based violence (GBV); they are making or influencing policy and serving as political leaders; or they’re confronting issues and want assistance advancing their own leadership as women. To correspond with these focus areas, Vital Voices has several teams that operate differently based on their mandate and the needs of the women they work with around the world.

For example, one of the many efforts Vital Voices’ human rights team oversees is an Urgent Assistance Program that provides emergency financial support to survivors of extreme GBV around the world. This program and others are made possible through the Voices Against Violence: The GBV Global Initiative, a public-private partnership between Vital Voices, the Department of State, and the Avon Foundation for Women. If an individual is experiencing an extreme form of GBV, they – or an organization or individual that is helping them – can contact Vital Voices’ GBV experts with linguistic support for short-term lifesaving assistance for their needs in the immediate aftermath or threat of extreme violence.

“The reality is we have varied and diverse program offerings because we realize that the needs of women leaders around the world are not one-size-fits-all,” says Hauspurg. “Women everywhere are blazing trails around solutions that are responsive to the local, national, regional and global challenges that impact them and the intersecting communities of which they are a part.”

Vital Voices’ program offerings have expanded to reflect what the women in their network have expressed they need support with. Most of the human rights teams’ work, therefore, focuses on domestic violence, sexual violence, human trafficking, harmful traditional practices, female genital mutilation and early and forced marriage. Although other teams engage with human rights advocates and defenders who promote a broader spectrum of human rights, the human rights team works exclusively on GBV.

“We realized that one in three women experience violence in their lifetime, so if we want women to advance in all areas of society – to get to be entrepreneurs, to get to be political leaders – fundamentally, we have to create an environment that’s free of violence and exploitation,” says Hauspurg.

One way that Vital Voices is tackling human trafficking, for example, is through its Global Freedom Exchange, a two-week educational and mentoring program in partnership with Hilton that takes anti-trafficking advocates – many of whom identify as survivors of trafficking themselves – to three U.S. cities, each with their own unique challenges and best practices in preventing and responding to trafficking. The program is complemented by regional programming as well as competitive grants, which support participants as they adjust the models they observed to their own contexts. Among the program’s alumni are two Seattleites: Wendy Barnes, who is the program director of Dignity Health’s Human Trafficking Response Program and Alisa Bernard, the director of education and partnerships at the Organization for Prostitution Survivors.

Also through VAV, Vital Voices has conducted two dozen Justice Institutes on Gender-Based Violence in 14 countries. Justice Institutes train judges, prosecutors, law enforcement, advocates and other community leaders involved in the justice system on how to more effectively identify, investigate and prosecute GBV – and why it’s important to do so. Especially with the help of male allies, Justice Institutes are helping to shift societal attitudes and enforce laws and policies that either don’t exist or aren’t implemented to their full extent.

Brazil, for example, didn’t have a domestic violence law until 2006. When the law was finally introduced, it wasn’t enforced and many women had no idea they had rights. Says Hauspurg, “Sometimes laws need help keeping their promises.” That inspired interest in Justice Institutes in Brazil, of which there have been five implemented in partnership with Vital Voices and local stakeholders. Moreover, it inspired Panmela Castro, a graffiti artist who was a young bride and victim of domestic violence, to begin painting beautiful murals late at night that depicted women as survivors and educated them about their rights under the new law. But to really scale her impact, Panmela needed leverage, so Vital Voices connected her with other graffiti artists and helped her establish Artefeito, an organization that uses art to transform culture for social progress.

A workshop in NYC, led by Panmela Castro, a graffiti artist who was a victim of domestic violence. Vital Voices connected her with other graffiti artists and helped her establish Artefeito, an organization that uses art to transform culture for social progress. Photo courtesy of Vital Voices Global Partnership.

As we approach the 25th anniversary of the conference that sparked this journey for Alyse Nelson and the tens of thousands of women, like Panmela, who have been impacted by her work, Vital Voices is looking for ways to continue building on the momentum of the last 25 years. One way is by adding new and different types of actors to their already extensive list of multi-sectoral partners, which currently include the U.S. Department of State, CARE, Avon, Hilton, Uber, Promundo, and Global Fund for Women, among others. They’re also always looking for more ways to include more women, whether by seeking creative methods of outreach, ensuring that as much as possible programming and services can be delivered in local languages, providing different forms of transportation to their programs or using pseudonyms for survivors – because the more women leaders they can reach, the more those women can pay it forward. And that’s the power of empowering women.

Back to Top

Goalmaker

Amanda Klasing, Human Rights Watch Acting Co-Director, Women’s Rights Division

By Penny Carothers

Growing up in South Texas close to a fluid border, Amanda Klasing saw deep inequality firsthand and wanted to do something about it from an early age. From a deeply religious family whose faith was informed by social justice, she always knew she’d have a career and a life that included service. What she didn’t realize then was that her life’s work would require her to face an inherent tension in her upbringing.

Growing up in South Texas close to a fluid border, Amanda Klasing saw deep inequality firsthand and wanted to do something about it from an early age. From a deeply religious family whose faith was informed by social justice, she always knew she’d have a career and a life that included service. What she didn’t realize then was that her life’s work would require her to face an inherent tension in her upbringing.

This tension was a fact of life in her childhood, streaming from the radio and from the front seat of the family car. On rides to and from baseball practice—on a team where she was the only girl—she heard messages like, “feminazis are going to ruin the world,” from the family’s favorite radio program, The Rush Limbaugh Show. “I grew up in a very conservative household where the worst thing that you could be was a feminist,” she explained. “At the same time, my dad also encouraged me to pursue anything that I wanted to, whether it was sports or leadership or a scholarship. Whatever it was, there was no distinction in the way that he saw my abilities and my opportunities and the way he saw my brother’s.”

Buoyed by her parents unflagging belief in her, Klasing excelled as a student and discovered human rights as a framework for understanding the social justice messages of her youth. While in law school and graduate school, she focused on human rights advocacy, which led her to Human Rights Watch (HRW) where she is now acting co-director of the women’s rights division.

Human Rights Watch’s Women’s Rights Division (WRD) has been protecting the rights of women and pushing for gender equity for 30 years. Their in-depth research and targeted advocacy have achieved impact around the world, from global treaties protecting the rights of women workers to national-level policy changes to advance reproductive rights, end child marriage, increase access to education, and protect women from violence.

At HRW Amanda has carried out research and advocacy on a number of human rights issues including the First Nations water crisis in Canada; sexual violence and other forms of violence against women displaced by conflict in Colombia; the relationship between women’s and girls’ human rights and access to good menstrual hygiene management; and the rights to water and sanitation in schools.

Amanda began documenting and elevating the experiences and the voices of those impacted by human rights violations, and she’s always learned from the people she meets. During research and advocacy work in Colombia, Amanda met Angélica Bello, a woman who was targeted by paramilitary successor groups in Colombia for her activism. Angélica and her daughters were victims of sexual violence. Rather than stay silent, she used her voice to call for an end to impunity for perpetrators. Angélica was a tireless advocate for survivors, helping them pursue justice for rape or assault and for increased access to protection and medical help. Despite threats against her life, Angélica kept highlighting the issue of sexual violence and the protections victims needed from the government. For her work, she was harassed and threatened relentlessly. Angélica died never receiving the psychosocial support she needed and was advocating to make available to all survivors. A year after Angélica’s death, a bill protecting the rights of survivors of sexual violence passed into law.

Several years later Amanda met Carol, a young mother in Brazil. Carol’s second daughter, Gabi, was born with congenital Zika syndrome. “Carol knew that something deeply wrong had happened, that there were so many government failures leading up to the Zika outbreak and afterward, and that her child and family have a right to receive services,” Klasing explained. Amanda worked with Carol to tell the stories of women and babies affected by Zika in northeastern Brazil and to create an HRW report on the issue. Amanda says, “I saw amazing growth in Carol and in her work with us and her community—the change that she will continue to have with other children and families is phenomenal and exponential.”

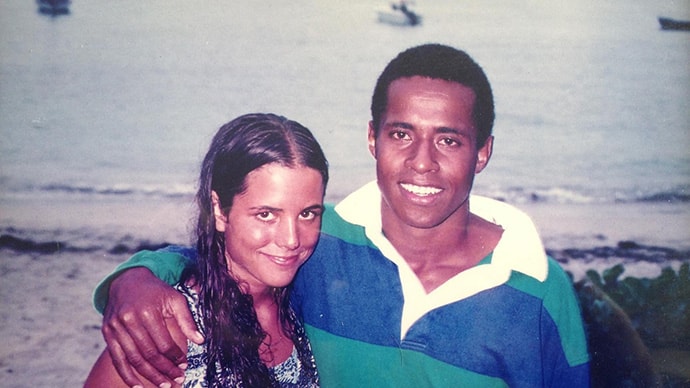

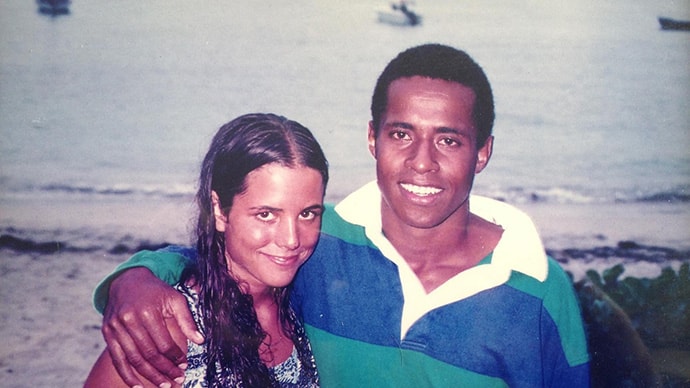

Maria Carolina Silva Flor and Joselito Alves dos Santos with their 18-month-old daughter, Maria Gabriela Silva Alves, pictured after the launch of the Human Rights Watch report Neglected and Unprotected, July 2017. © 2017 Amanda Klasing/Human Rights Watch

As Amanda emerged as a leader in the women’s rights movement , she continued to grapple with a tension she sees in her work with women like Carol and Angélica: incredible human rights violations juxtaposed with the strength she sees in survivors as they persevere and demand respect for their rights even while facing daily indignities and atrocities. This is what is at the heart of the human rights movement: survivors seeking justice and to be seen as having the same inherent dignity as all human beings. It’s one of the reasons she was drawn to and keeps doing the work. “The brave women and girls who I have spoken to throughout my career continue to motivate me and in particular the leaders that rise out of movements at the grassroots level. I have felt very fortunate to work with women’s rights advocates and I am amazed by their fortitude and their ability to hope for a different world.”

Despite the difficulties, Amanda is encouraged by advances in centering human rights conversations on impacted populations. HRW has always strived to promote a connected, outspoken, and effective global women’s rights movement that is intersectional and inclusive. She says, “My personal and professional goal is to see human rights organizations adapt to be in service to a movement and to the leaders of directly impacted populations. There’s so much space for innovation and opportunity to bring our research methodologies and unique strengths to partner for new approaches…My colleagues at HRW are always willing to evolve and be influenced by our partners.”

You can say the same about Klasing. Though she prefers to talk about her work and the strength of grassroots leaders rather than herself, it is striking that in her role at HRW Klasing broadcasts a different kind of story than the one she grew up listening to on the radio. The tension between the messages she heard as a child and those she shares now may be strong, but the connection is undeniable. She summed it up best herself in a 2017 article for Women’s eNews when she said, “My father exposed me to what the world thinks of women who fight too hard for equality, but also raised me to be strong enough to be one of those women.”

Back to Top

Welcome New Members

Please welcome our newest Global Washington members. Take a moment to familiarize yourself with their work and consider opportunities for support and collaboration!

Fanikia Foundation

Fanikia Foundation provides support to underprivileged individuals and communities in Tanzania and the United States through education, training, and information. Its main goal is to eliminate poverty and to empower individuals in specific communities. Different strategies are needed to tackle these issues. The foundation partners with like-minded organizations to eliminate poverty and illiteracy. Currently Fanikia Foundation is focusing on two programs: “Educate a Girl,” a program based in Tanzania and “Drive to Higher Education,” based in the United States. fanikiafoundation.org

Vital Voices

Vital Voices is a global movement that invests in women leaders who are solving the world’s greatest challenges. Guided by the belief that women are essential to progress in their communities, Vital Voices identifies women with a daring vision for change and invests in them to make their vision a reality. Through long-term investments that expand each leader’s skills, connections, and visibility, Vital Voices accelerates and scales their impact. vitalvoices.org

Back to Top

Member Events

Many member events in March have been cancelled or are now being held virtually. You can find out about upcoming events on our Community Calendar.

Back to Top

Career Center

Research and Impact Officer, Global Partnerships

Director of Communications and Marketing, Tearfund

Assistant, VillageReach

Global Entersprise Director, Days for Girls

Enterprise Program Administrative Assistant, Days for Girls

Check out the GlobalWA Job Board for the latest openings.

Back to Top

GlobalWA Events

March 18: (Virtual Event) Proven strategies for stopping gender-based violence

Back to Top

Climate justice means protecting the future of fish

Posted on February 18, 2020.

By Kelly Pendergrast, Communications Consultant at Future of Fish

Boats arranged on the beach in Paita, Peru. Photo courtesy of Future of Fish.

Billions of people depend on fish as a critical source of protein. From lobster divers in Belize to handline mahi-mahi fishers in Peru, communities around the world feed themselves and make a living from the fish they pull from the ocean every day. But these livelihoods are under threat. Climate change is already wrecking havoc for coastal communities in developing countries, with rising seas damaging dockside infrastructure and warming waters driving away traditional fish stocks. The result is loss of income, food, and in many cases, cultural heritage.

Continue Reading

February 2020 Newsletter

Posted on February 6, 2020.

Welcome to the February 2020 issue of the Global Washington newsletter.

IN THIS ISSUE

Letter from our Executive Director

When I hear people in developing countries talk about climate change, it’s often about droughts, famines, increased disease, loss of income, or forced migration. It’s a devastating new reality and it’s clear that those who continue to be hardest hit by the effects of climate change tend to be those who can least afford it.

Former President of Ireland Mary Robinson states, “the fight against climate change is fundamentally about human rights and securing justice for those suffering from its impact.” She speaks of “Climate Justice” and elevates solutions to climate change that put those most vulnerable at the center. I couldn’t agree more.

In addition, many of those on the frontlines of climate change are also the leaders we need for smart and sustainable adaptation and mitigation efforts. Global Washington has amazing members elevating local leaders such as Rise Beyond the Reef, founded by an inspiring couple in Fiji who are listening to local wisdom and creating community around an abundance mindset – one that respects “the connection between land, food, traditional knowledge, identity and innovation.”

And closer to home, the Seattle Foundation is supporting communities of color and low-income populations as those most impacted by climate change in our region. Their focus is on a more human-centered climate response for long-term systems change.

I hope you enjoy the discussions this month and I encourage you to share what you are learning with others so that more people can benefit and be part of this important conversation.

Kristen Dailey

Executive Director

Back to Top

Issue Brief

“Climate Justice” Advances Discussion of Climate Change Risks and Response

By Joanne Lu

A woman in Fiji cultivates her crops. Photo credit: Rise Beyond the Reef.

On April 22, 1970, 20 million Americans celebrated the first Earth Day as a peaceful demonstration for environmental reform. Fifty years later, it’s now celebrated around the world and has paved the way for efforts like the Environmental Protection Agency, the 1992 United Nations Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro and the Canopy Project. But these efforts have not been enough, and more than ever, the world is wrestling with the risks and effects of climate change, particularly on the world’s most vulnerable communities.

Last month, in the 50th edition of the World Economic Forum’s annual Global Risks Report, all five of the top risks were environmental, including damage from extreme weather events, the failure of climate-change mitigation and adaptation by governments and businesses, human-made environmental damage and disasters, biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse, and natural disasters. Although climate change is happening everywhere, research repeatedly shows that those who are already struggling with poverty, oppression and instability are being affected the most and will increasingly bear the consequences. That’s because the injustices associated with poverty, age, gender, social exclusion and weak infrastructure undermine these populations’ ability to cope with climate change.

For example, according to the World Bank, 78 percent of the world’s poor live in rural areas and most of them rely on agriculture for their livelihoods. That means that shifting weather patterns, rising temperatures, extreme weather events like floods and droughts and land degradation are putting the poor at greater risk of losing their livelihoods, being unable to feed their families, sinking further into poverty and maybe even being forced to migrate. By 2030, the World Bank estimates that food prices could be 12 percent higher on average in sub-Saharan Africa because of crop yield losses from climate change. Combined with the other effects of climate change – including increased conflicts and deadly infectious diseases – the World Bank warns that more than 100 million additional people could be living in poverty by 2030, and most of them will be in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

What’s even more unfair is that in many cases, the communities that are most affected are the ones which have contributed the least to climate change. The island nation of Kiribati, for example, is one of the lowest emitters of carbon dioxide in the world. Yet, because of top polluters like the U.S. and China, Kiribati is literally disappearing beneath a rising sea. In 2016, the UN Institute for Environmental and Human Security reported that 94 percent of people living on Kiribati had already been impacted by climate change.

While developing countries are suffering the most from climate change, vulnerable communities in wealthy countries are being disproportionately affected, as well. A federal report published in 2018 concluded that low-income communities and some communities of color, many of which are already overburdened with poor environmental conditions and adverse health conditions, are less resilient to and disproportionately affected by extreme weather and climate events, including the health impacts. In Washington state, for example, Seattle Foundation says that “46 percent of all toxic sites are in areas mostly populated by people of color, while 56 percent are in largely low-income areas.” These communities, therefore, are struggling with contaminated drinking water, poor air quality, unhealthy housing and extreme weather events. Because of discriminatory zoning, banking and employment practices, people in these communities also have the least access to tools that would help them cope, such as transportation, education, insurance and healthy housing.

While developing countries are suffering the most from climate change, vulnerable communities in wealthy countries are being disproportionately affected, as well. A federal report published in 2018 concluded that low-income communities and some communities of color, many of which are already overburdened with poor environmental conditions and adverse health conditions, are less resilient to and disproportionately affected by extreme weather and climate events, including the health impacts. In Washington state, for example, Seattle Foundation says that “46 percent of all toxic sites are in areas mostly populated by people of color, while 56 percent are in largely low-income areas.” These communities, therefore, are struggling with contaminated drinking water, poor air quality, unhealthy housing and extreme weather events. Because of discriminatory zoning, banking and employment practices, people in these communities also have the least access to tools that would help them cope, such as transportation, education, insurance and healthy housing.

The federal report also attributes part of the problem to the fact that these vulnerable populations are often excluded in planning processes. That’s why the Seattle Foundation launched its Climate Justice Impact Strategy to ensure that communities of color and low-income communities are “leading and shaping efforts to reduce the disproportionate effects of climate change that they experience.”

World Vision also works closely with communities around the world to identify solutions that work for their individual contexts. In Ethiopia, for example, World Vision wanted to address the health problems, carbon emissions and deforestation associated with open cooking fires. So, they worked with women to determine what kind of fuel-efficient and environmentally friendly cookstoves worked best for their needs, and they have since distributed tens of thousands of them across the country.

In India, Earthworm is also helping smallholder farmers become more resilient in the face of climate change by helping them nurture the country’s soil back to health. The Mitti Bole program (or Soil Speaks) brings together international soil experts, Indian organic farming pioneers and other researchers to educate farmers on responsible soil and water management, agroforestry to improve soil quality and sequester carbon as well as ways to reduce their pesticide and fertilizer dependence.

Experts are recognizing, too, that any effective response to climate change must take gender into account, because women and girls are disproportionately affected. Part of this is because 70 percent of the world’s poor are women and girls, but also societal roles, gender-specific health concerns and discrimination play a big part. For example, when Cyclone Idai hit Mozambique, Malawi and Zimbabwe last year, 75,000 pregnant women were affected, with 7,000 at risk of “life-threatening complications” because the flooding and destruction obstructed access to clean water, sanitation and reproductive health care. Domestic work and caregiving duties – women and girls’ primary responsibilities in many contexts – also become much more difficult and time-consuming with climate change. And if they are displaced from their homes by an extreme weather event, they face a greater risk of exploitation and sexual violence.

But women and girls have a crucial role in climate change adaptation and mitigation. That’s why Project Drawdown, a repository for substantive solutions to climate change, focuses to a large extent on women and girls, including girls’ education. Education, they say, “lays a foundation for vibrant lives for girls and women, their families, and their communities,” but it also helps curb carbon emissions because women with more education tend to have fewer and healthier children. Education can also help girls and women become more productive and responsible food providers with a greater capacity to cope with climate shocks.

Remote Energy is also helping more women get involved in climate solutions in a technical capacity. Their program equips women in developing countries with the technical skills and a community of support to become solar electric technicians. This not only opens up economic opportunities for women, but also gives them a greater voice in decisions about energy within their communities. After all, in developing countries, women are the main users of household energy, so training them in renewable technologies makes their work more sustainable and efficient, which also gives them more time to pursue education and income-earning activities.

All of these programs illustrate the core principles of climate justice as laid out by the Mary Robinson Foundation. We must remember that climate change is not just an environmental or physical problem; it also contains ethical and political dimensions.

The core principles of climate justice are as follows: 1) respect and protect human rights 2) support the right to development 3) share benefits and burdens equitably 4) ensure that decisions on climate change are participatory, transparent and accountable 5) highlight gender equality and equity 6) harness the transformative power of education for climate stewardship and 7) use effective partnerships to secure climate justice.

These principles are not new, the foundation says, but should help those in pursuit of climate justice achieve a human-centered approach – one that shares the burdens, benefits (wealth from emissions, for example) and responsibility for solving climate change fairly and equitably, and, perhaps most importantly, protects the rights of the most vulnerable.

# # #

The following Global Washington members are working to address climate change and its impacts on the most vulnerable communities around the world.

Earthworm

Earthworm Foundation (formerly known as The Forest Trust) has 20 years of experience in finding solutions to the major social and environmental problems that our world is facing today. Earthworm’s vision is for future generations to not simply survive, but to thrive. The nonprofit seeks to build a world where the balance between people and the environment, value and profit, people’s beliefs and actions is maintained and where human, natural and capital resources become a force for good. For that, Earthworm sees a world where forests are a boundless source of materials and a home for biodiversity; communities see their rights respected and have opportunities to develop; workers are seen as productive partners; and agriculture becomes the instrument to feed a hungry planet and keep our climate stable.

FSC Investments & Partnerships

Forest Stewardship Council Investments & Partnerships (FSC I&P) is the Seattle-based branch of FSC. As the original pioneers of forest certification, FSC has over 25 years of experience in sustainable forest management. FSC promotes the responsible management of the world’s forests, and has developed a high standard of forest management that prioritizes the environmental, social and economic rights of community foresters, and indigenous people around the world. FSC I&P’s mission is aligned with the FSC in promoting environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial, and economically viable management of the world’s forests. In 2018, FSC launched its Ecosystem Services Procedure, which allows businesses and governments an additional mechanism to demonstrate the impact of their products and investments on watershed services, carbon sequestration and storage, and biodiversity conversation, among other ecosystem services. Recently, FSC Canada received funds from the Canadian Ministry of Environment and Climate Change to support implementing the new Canadian National Forest Standard, the result of five years of rigorous consultation with indigenous groups, environmental and social stakeholders, and industry actors. It addresses the most pressing issues facing Canadian forests, including preserving the threatened woodland caribou, Indigenous people’s rights, worker’s rights, including gender equity, and landscape management and conservation.

Future of Fish

Future of Fish works to ensure sustainable livelihoods for fishing communities and long-term health of wild fish populations, which billions of people depend upon as a critical source of protein. Climate change is already wreaking havoc for coastal communities in developing countries, with rising seas damaging dockside infrastructure and warming waters driving away traditional fish stocks. The result is loss of income, food, and in many cases, cultural heritage. Future of Fish collaborates with small-scale fishers to design better systems, practices, and technologies that help fishers continue supporting their communities in a time of unstable climate impacts. Climate justice is only possible when front-line communities have the resources they need to survive and thrive. Future of Fish works closely with fishers, seafood supply chains, and the local community and governments to co-design interventions that build environmentally sustainable, climate resilient, and economically viable fisheries. With support from global and regional partners, Future of Fish helps address food security and achieve long-term social and environmental impact for coastal fishing communities around the world.

Heifer International

Heifer International is on a mission to end global hunger and poverty in a sustainable way. For over 75 years, the organization has invested alongside more than 35 million farmers and business owners around the world, supporting them to build businesses that deliver living incomes and protect the environment. Heifer works with smallholder farmers using a tried and tested community development model, providing farming inputs that enable them to grow their businesses using locally available resources. Expert teams and partners provide training in climate smart agriculture techniques so farmers can increase their resilience to climate change, improve production, restore soil health and reduce deforestation. Many of the communities Heifer works with are among the most vulnerable to climate change. Heifer works with them to manage grazing, protecting areas of important biodiversity, enabling farmers to make a living income and restore resources for future generations. Heifer also invests alongside farmers in clean, green energy solutions, like solar power systems and biogas, so they can generate the energy they need to power their continued growth. Heifer believes local farmers hold the key to feeding the world, and it is working with them to make their farms sustainable in every sense of the word.

Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch conducts on-the-ground research to document the impact of climate change and climate-harming activities and to advocate for positive change locally, nationally, and internationally. We disseminate our findings through our global media network and 11 million social media followers. We use our findings and media exposure to urge governments and corporations to implement rights-respecting environmental policies and practices, with a focus on the disadvantaged populations that are suffering harms most acutely. In coalition with other environmental and human rights groups, we successfully advocated for the inclusion of human rights language in the landmark 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change. In the coming year Human Rights Watch’s work on climate change will focus on two of today’s most urgent issues: protecting forests that serve as critical “carbon sinks” and accelerating a global shift away from the use of coal, one of the dirtiest fossil fuels. We will undertake research and advocacy on issues including food insecurity for Indigenous communities in Canada and the ways in which climate-harming activities, like coal emissions in Europe and Africa and deforestation in South America, also harm human rights.

Mercy Corps

The climate crisis is creating unprecedented challenges for millions of people already burdened by poverty and oppression. Mercy Corps’ climate resilience work tackles the human impacts of climate change—particularly disappearing livelihoods, rising food insecurity, increasing disaster, and escalating violence—by empowering communities to adapt, innovate and thrive. Mercy Corps tackles the root causes of instability, empowering people to survive crisis and transform their communities. As climate change is a key driver of events such as floods and droughts that undermine development gains and threaten vulnerable people, Mercy Corps partners with local communities to rebound from disasters while helping them be more prepared for the next ones. In Mali, Mercy Corps partnered with local communities, through a cash for work program, to construct dams along the Niger river to secure communities against flooding and conserve water for off-season farming. As a result, for the first time in 30 years, 250 families in the Tassakane village of the Timbuktu region didn’t suffer from flooding during the rainy season

Microsoft

Microsoft’s mission is to empower every person and organization on the planet to achieve more. This includes working with enterprise customers as well as non-profits and NGOs around the world to scale the impact of their work. Microsoft is empowering first responder organizations to meet critical global needs, humanitarian organizations to drive greater impact, and displaced people to rebuild their lives with a mix of technology, cash grants, employee donations and staff time. This mission-driven work is evident in its environmental work, which began in 2012 as a carbon neutral company. In responding to the urgency of climate change, Microsoft recently made three commitments: 1) the company will become carbon negative by 2030; 2) it will take responsibility for removing its historical carbon emissions by 2050; and 3) it will invest $1 billion over the next four years into new technologies and expanded access to capital for those working around the world to solve climate change.

National Wildlife Federation

As the U.S. confronts the cascading impacts of a changing climate, advancing environmental justice must be central to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, boosting resilience, and revitalizing communities. Low-income and communities of color are disproportionately impacted by the effects of a changing climate—and the National Wildlife Federation has a responsibility to empower frontline communities to enact transformative change by providing resources and tools. To achieve this vision, for both people and wildlife, NWF is working to ensure that equity and the principles of environmental justice are institutionalized into its climate work. One way is through Revitalizing Vulnerable Communities Institute, which is empowering communities to implement holistic solutions to environmental and economic issues. The Federation is also undertaking a Climate and Communities Project that works to help communities heavily dependent on fossil fuels feel more prepared for, and engaged with, national climate policies. Here in the Pacific Northwest, the National Wildlife Federation is engaged in climate change issues unfolding in the Columbia River basin and the Snake River. Hotter water temperatures are pushing cold water fish—including salmon—toward extinction, greatly impacting the inland and coastal Native American communities, and as well as rural fishing communities that depend on them.

Oxfam America

Oxfam America believes that the injustice of climate change is also the injustice of inequality – those who have done the least to contribute to global emissions are the hardest hit. Climate justice requires that we rapidly shift towards low-emissions economies that leaves no one behind, and promote resilient development by building capacities and leadership of communities & womenon the frontlines. The climate crisis is already impacting the world – wildfires in Australia, locusts in Africa, and communities in the global south are often the hardest hit with extreme weather events like droughts and floods taking a heavy toll. Oxfam’s vision and value add in the fight for climate justice centers these communities unlike other organizations that focus on wildlife preservation or more narrowly on environmental impacts. Through its work, Oxfam is committed to reducing climate change by tackling the structural drivers of the crisis often rooted in unequal economic models, which requires holding governments and big business accountable. Oxfam works with a range of partners to help communities adapt and become more resilient, and are committed to elevating the voices and leadership of communities – especially women who are on the frontlines. Oxfam also believes that policy and advocacy have key roles to play to advance climate justice. Oxfam works to defend the Paris agreement and engage the US government to push for a robust global framework to tackle the climate crisis. Oxfam engages food and beverage companies to tackle the hidden emissions in their supply chains; advocates with international finance institutions to channel more investment towards pro-poor clean energy; works toward greater transparency in the oil and gas sector; and encourages governments to invest in the rights and livelihoods of small famers, especially women farmers.

Remote Energy

Remote Energy (RE) believes that access to reliable sources of sustainable energy is a fundamental requirement for the advancement of education, healthcare, economic opportunity and quality of life. It is also a critical step in mitigating the effects of climate change. The climate crises has fostered significant growth in the solar energy industry worldwide, and has fueled the fast growing need for a trained solar workforce. RE has responded by developing and implementing regionally appropriate, customized technical capacity building programs and developing hands-on, practical learning opportunities for solar technicians and instructors in marginalized communities worldwide. RE’s scalable programs, methodology and mentorship opportunities provide the knowledge, technical skills and support network for inspiring people and communities to move towards energy independence and sustainable development. RE is also committed to gender equality and supports the belief that women’s talents and leadership are vital to maintain a diverse, sustainable PV industry and critical in the fight against climate change. RE’s Women’s Program is designed to develop women decision-makers, end-users, technicians, and educators and offers customized, women’s-only courses and mentoring opportunities with professional female instructors.

Rise Beyond the Reef

Rise Beyond the Reef bridges the divide between remote communities, government and the private sector in the South Pacific, sustainably creating a better world for women and children. There is no reason not to value the inherent intelligence and resilient nature of Pacific Island cultures that have self-sustained for thousands of years. Rise Beyond the Reef believes that if leadership in remote communities can be cultivated and strengthened, if these fire-keepers of traditional knowledge can have a place where they are protected, ignited and supported to grow sustainably in the 21st century, if women have an equal voice that’s heard and respected in their communities, if their experiences and insights are valued, if children’s rights are protected, then the entire community will rise. It’s not about helping the poor or just focusing on the environment, it’s about creating value around the important role remote communities play in our world’s whole picture, including creating a stable climate. It’s about valuing rather than extracting. It’s about supporting rather than directing. It’s about seeing our collective future. That’s when we all rise together.

Seattle Foundation

Seattle Foundation ignites powerful, rewarding philanthropy to make Greater Seattle a stronger, more vibrant community for all. As a community foundation, it works to advance equity, shared prosperity, and belonging throughout the region while strengthening the impact of the philanthropists they serve. Founded in 1946 and with more than $1.1 billion in assets, the Foundation pursues its mission with a combination of deep community insight, civic leadership, philanthropic advising and judicious financial stewardship. The Climate Justice Impact Strategy is Seattle Foundation’s comprehensive approach to ensuring that communities of color and low-income communities are leading and shaping efforts to reduce the effects of climate change, which they experience disproportionately. To reduce the risks of climate change, we address its root causes, identify and adapt to its impacts, and strengthen community resiliency to those impacts. Justice and equity are at the core of this approach, which uses community-based research while building diverse coalitions and increasing the capacity of nonprofits to advance local solutions to this global challenge.

Snow Leopard Trust

The Snow Leopard Trust (SLT) seeks climate justice through its mission to protect snow leopards in partnership with local communities that share the cat’s habitat. For nearly four decades, SLT has worked to empower herding families across Asia to take action for their local ecosystems and secure a prosperous future for both humans and wildlife. With programs and staff in five countries in Asia and support from around the world, SLT coordinates programs that promote sustainable development, green livelihoods, and climate-smart planning, including environmental education camps, livestock insurance and vaccination programs, ranger trainings, and a handicraft program called Snow Leopard Enterprises. Using approaches from both natural and social sciences, SLT researchers endeavor to understand the complex dynamics between people, predators, and the environment. SLT has been a key partner in the Global Snow Leopard & Ecosystem Protection Program (GSLEP) and rallied the governments of 12 countries to support programs that link conservation with sustainable development. As humankind expands its reach to the most remote areas of snow leopard habitat, SLT strives for climate justice through community involvement and multilateral partnerships.

Tearfund USA

In 1992, Tearfund became the first large international development NGO to focus on the climate crisis after seeing how it affected the organization’s partners across the globe. The rate and impact of environmental degradation are hitting people living in poverty the hardest – the very people who have done the least to cause it. To combat this issue, Tearfund supports communities with programs related to waste management, renewable energy, climate-smart agriculture, and climate resilience. Through Tearfund’s training and equipping programs, vulnerable communities are able to produce enough food for everybody using environmentally responsible farming methods. This way they become part of a sustainable future. Tearfund also calls on governments and companies to change harmful practices that contribute to climate problems. Currently, Tearfund is working in more than 24 countries to address the challenges caused by the climate crisis, furthering its efforts in advocacy, campaigning, and supporting environmental sustainability programs.

Vulcan

To address climate change Vulcan philanthropy funds projects and investments in research, innovation, and policy change. One innovative project for example is improving researchers’ ability to understand sea ice in response to climate change. Through the Foundation and personal philanthropy, Paul G. Allen and Vulcan have provided more than $50 million for forest preservation, research, education, development and management, protecting key land and habitats in the Pacific Northwest and around the world. In addition, Vulcan Production films, such as Racing Extinction and Pandora’s Promise help audiences understand the effects of climate change and spark a dialogue about solutions. On the policy front, Paul G. Allen and the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation joined a lawsuit to require the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management to prepare a programmatic environmental impact statement for the federal coal leasing program. In a blog post, Allen said “It is time for our government leaders to make informed decisions on how to best manage our public resources to meet our nation’s energy needs.”

Woodland Park Zoo

More than a million vulnerable species need humans to take action for their survival. Meaningful reductions in carbon emissions to avert the worst impacts of the climate crisis require behavioral, organizational and policy change. Woodland Park Zoo has joined The Wave, a coalition of more than 100 Pacific Northwest organizations pledged to fight for 100% clean energy, zero waste, and clean air and water for every living creature. Through exceptional animal care and sustainable practices such as solar panels, eliminating single-use plastics, investing in green infrastructure, and converting our animals’ waste into ZooDoo compost – Woodland Park Zoo continues to inspire our community and nearly one million unique visitors a year to make conservation, and sustainability, a priority in their lives.

World Vision

World Vision is a Christian humanitarian organization dedicated to working with children, families, and their communities worldwide to reach their full potential by tackling the root causes of poverty and injustice. World Vision works directly with communities to identify context-specific solutions with a focus on food security, clean energy, natural resources management and climate adaptation and mitigation. Projects include interventions like reforestation, agro-forestry, climate-smart agriculture, clean energy and access to carbon markets. World Vision Australia is also a world leader in promoting Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR) in rural communities, a process that naturally regenerates trees on farmland and forest areas to improve agricultural productivity and reduce the incidence of droughts, floods and landslides. A number of communities in Ethiopia have also benefited from the Clean Stoves Project, which reduces the health risks associated with smoky open fire stoves, and reduces the need to cut down trees. Finally, World Vision has worked with communities in South East Asia and the Pacific region to better prepare them for tropical storms and other natural disasters, which are becoming increasingly frequent and violent as a result of climate change.

Back to Top

Organization Profile

Local Philanthropic Institution, Seattle Foundation, Has Begun a New Chapter Addressing Climate Justice

By Stephanie Stinson

2017 Earth Day climate march in Seattle. Photo credit: Rick Theis, Twenty20.

Community foundations first emerged as U.S. institutions more than 100 years ago. Since then they have become essential bridge builders, civic leaders, and philanthropic catalyzers in the places they serve.

Closer to home, the name Seattle Foundation has long been synonymous with efforts to strengthen the health and vitality of our region through philanthropy since its creation in 1946. Each philanthropic strategy designed by Seattle Foundation is rooted in the belief that all individuals, families, and communities deserve opportunities to thrive, regardless of their race, place, or other identity. In line with its tradition as a recognized leader in striving to reduce the inequities that exist across our local communities, Seattle Foundation launched a Climate Justice Impact Strategy in 2018 to guide the evolution of its ongoing commitment to this work.

Part of a broader Community Program practice area, the Climate Justice Impact Strategy endeavors to address the disproportionate impacts of climate change on communities of color and low-income communities, while also ensuring these communities themselves are at the frontline in designing initiatives to address a changing climate. The strategy document states: “Everyone has a stake in achieving climate justice and we believe that focusing on those first and worst impacted ensures that we all thrive.”

Sally Gillis, the managing director of strategic impact and partnerships at Seattle Foundation, oversees the Climate Justice Impact Strategy. Drafted with an eye towards long-term systems change, Gillis said that the strategy recognizes the importance of concurrent efforts around mitigation, adaptation resilience and leadership.

After launching its climate justice strategy, the Seattle Foundation undertook its first major action in this area – the endorsement and support of Washington state Initiative 1631, a carbon emissions fee. “This for us was a strong step forward in speaking to our commitment, using our voice as a civic leader in support of equitable climate change policies that truly support frontline and marginalized communities,” said Gillis. “We continue to see policy as a critical lever. While the initiative wasn’t successful, I’m proud that we stood on the right side of history in speaking to our values.”

When asked what particular policies Seattle Foundation anticipates supporting in 2020, Gillis commented that the organization will be keeping an eye on what unfolds during this legislative cycle to then inform future ballot priorities. She also noted that Seattle Foundation relies on its community partners to elevate ways the organization can be most valuable.

“There is great effort through many of our grantees to put progressive policies on the ballot and in front of the legislature, recognizing that if we don’t act quickly, climate justice is going to be harder and harder to be realized.”

A fundamental component to the strategy’s approach includes producing more prominent messaging around the human-centered impacts that communities of color and low-income communities face in a changing climate. It is widely documented that in the United States, race is the most significant predictor of a person living near contaminated water, air, or soil. Locally, this is evidenced by the fact that 58 percent of the population that lives within one mile of the Duwamish River Superfund boundary are people of color. To this end, Seattle Foundation is using storytelling to better illuminate the complexity and humanity of climate justice.

Last August Seattle Foundation invited 20 philanthropists to join Puget Soundkeeper and Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition on a boat tour of the Duwamish River. This gave philanthropists the opportunity to reflect on both the social and environmental consequences of a century of development in Seattle’s commercial district and how they wanted to be part of solutions moving forward.