August 2019 Newsletter

Posted on August 13, 2019.

Welcome to the August 2019 issue of the Global Washington newsletter.

IN THIS ISSUE

Letter from our Executive Director

Within the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), we often think of education (SDG 4) as a standalone goal, but it is important to remember that other SDGs have education-related targets, as well. Some of these include reproductive health education, as well as information on sustainability, including a better understanding of climate change. These interlinkages are critical, as education is an important catalyst for achieving sustainable development as a whole.

Arguably, one of the most complex of the Sustainable Development Goal targets is SDG 4.7, which deals with how we learn to live together – peacefully, equitably, and sustainably.

With this target in mind, for the month of August we are highlighting efforts underway in developing countries to teach students about ethical leadership, and why this matters for building more sustainable, inclusive, and resilient societies globally. With climate change and increasing economic and social pressures around the world, many difficult challenges lie ahead that young people will need to be prepared to solve.

In this month’s newsletter, you can read more about this ambitious SDG target, and learn how Ashesi University is educating the next generation of ethical, entrepreneurial leaders in Africa. You’ll also read about how the founder of the Mona Foundation, inspired by her faith, invests in educating and empowering girls, and why she emphasizes the importance of service to the community.

At Goalmakers, our annual conference in Seattle, we will continue exploring the interlinkages between the Sustainable Development Goals and highlighting how our members’ work is helping accelerate progress toward them. Please note the NEW DATE for our 2019 conference – Friday, November 15.

I hope you can join us!

Kristen Dailey

Executive Director

Back to Top

Issue Brief

Educating Ethical Leaders for a Sustainable Future

By Joanne Lu

At Commencement, Ashesi Provost, Angela Owusu-Ansah, confers degrees on members of the Class of 2019. Photo provided by Ashesi University Foundation.

We all know how important an education is for getting a good job. But education should be much more than job training. It is a human right with the power to break cycles of poverty, achieve peace, change values and behaviors for the better, and move entire nations up the ladder of development.

But simply teaching literacy and arithmetic or even vocational skills isn’t enough to unleash the full potential of education. It takes quality education that equips every individual with the ethics and skills they need to tackle the daunting challenges ahead as effective leaders for a sustainable future. Especially in the face of added climate pressures, quality education for sustainable development is more important than ever.

The UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimates that globally there are now 100 million more children in school than a decade ago. Under the UN’s Millennium Development Goals from 2010 to 2015, a concerted push to achieve universal primary education increased the primary school enrollment rate in developing countries to 91 percent, compared to 83 percent in 2000.

These improvements are critical to the world’s efforts to eliminate poverty. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Institute for Statistics (UIS) estimates that the number of poor people in the world would be reduced by 55 percent if all adults completed secondary education. That’s 420 million people lifted out of poverty, because of the social mobility offered by a good education.

But quality education is also an important enabler for other development goals, including good health, reducing inequalities, tackling climate change and building peace. In Indonesia, for example, a study found that education levels were an especially strong predictor of who survived the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami.

However, the world fell short of achieving universal primary education by 2015, and now it looks like we’re not on track to achieve the latest goal for education either.

Sustainable Development Goal 4 aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” by 2030. But progress has stalled, according to UIS, and an estimated 262 million children and youth between six and 17 years old are still not in school. That’s a staggering amount of kids who are being deprived of education because of injustices including war, famine, child labor and child marriage. They’re also at higher risk of exploitation because they’re not in school.

Much work has been done over the last couple decades to increase children’s access to education and encourage attendance – whether by building more classrooms, helping offset the cost of school books, fees and uniforms, or, in Brazil’s case, for example, even giving families a stipend in return for sending their children to school and getting immunizations.

Girls’ scholarships have also been very effective in not only providing access to girls whose families might otherwise prioritize boys, but also in keeping them out of child marriages. Educated mothers, too, are much more likely to make sure their own children go to school and complete their education. That’s why many organizations have made it a central focus to improve gender equality in education and promote a “gendered approach” – including safe, gender-separated and accessible toilets, reproductive and sexual rights education in curricula and the promotion of STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) subjects for women and girls. Although a gender gap persists (girls are 1.5 times more likely to be excluded from primary education than boys), today women (and men, too) are more educated than ever before.

Students participate in Sahar’s Early Marriage Prevention Program in Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan.

Photo credit: Freshta Ameri for Sahar.

With an increase of migration and displacement, children’s educations are also being disrupted, and the older a refugee gets, the less likely it is they’ll receive a quality education. According to the UN, less than a quarter of all refugees make it to secondary school, and a mere one percent makes it to university. Already overstretched refugee agencies are doing what they can to keep refugee and migrant kids in school, but much more still needs to be done.

The problem goes beyond just access to education, because even those who are attending school are not necessarily learning. An estimated 330 million children are in school but failing to learn, while only half of the adults in developing countries who have completed five years of school can even read a single sentence. UIS also projects that if current trends hold, four in 10 youth will have dropped out of secondary school by 2030.

The UN, World Bank and others call this problem the “global learning crisis.” A large part of the problem, they say, lies with a shortage of qualified teachers. In 2016, UNESCO warned that universal primary and secondary education would be impossible without 69 million new teachers, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. And data from the World Bank show that a substantial portion of existing teachers in Africa are functionally illiterate and innumerate. While almost 90 percent of teachers in Kenya could do a simple division problem, less than 6 in 10 teachers in Nigeria could do the same.

Solving this qualified teacher deficit requires investing heavily in teachers – in their wages, training, supplies and support system. And technology advances are making it easier. Remote teacher training platforms are now able to reach teachers in poor, rural areas that have relied for too long on rote learning and dictation.

New investments in teachers also creates an opportunity to expand students’ learning beyond just the basic subjects. We need to “ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development.” This is Target 7 under SDG 4.

As conflicts have become deadlier and more prolonged, as inequalities undermine and stall progress, and as climate change threatens the very existence of species and communities, we must prepare students today to become effective leaders and innovators of tomorrow. It is critical that they are empowered at every level – from primary school to university – to “change the way they think and work towards a sustainable future,” as UNESCO puts it.

Ashesi University in Ghana, for example, recognizes that university students will most likely be the future leaders of the African continent. So, in addition to equipping them with technical majors based on market needs, including computer science, engineering and business administration, they also aim to “cultivate within students the critical thinking skills, the concern for others and the courage it will take to transform the continent.” This understanding is built into their curriculum, into the teaching style of their professors, and into the culture of the school.

Even if we miss certain targets within the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, we can still lay the groundwork for achieving them down the road by making sure everyone has access to quality education that transforms the way we interact with our planet and each other for the better. This is the full potential of education.

* * *

The following Global Washington members are working to improve access to quality education around the world:

Ashesi University Foundation

Ashesi University aims to propel an African renaissance by educating a new generation of ethical, entrepreneurial leaders. Located in Ghana, this private, non-profit, liberal arts university combines a rigorous liberal arts core with degree programs in Computer Science, Business Administration, Management Information Systems, and Engineering. Ashesi invests in students from diverse economic, ethnic, religious, and national groups by building leadership development, character, and community service into a four-year curriculum. Upon completion, Ashesi graduates are emboldened to tackle persistent problems in their communities, create jobs, and lead with purpose. The Seattle-based Ashesi University Foundation exists to fundraise for Ashesi University and raise international awareness about the school’s impact. ashesi.org

BuildOn

For two decades buildOn has mobilized rural communities in some of the economically poorest countries on the planet. The organization builds schools with villages that lack adequate classrooms – where students learn in huts, are taught under trees, or walk miles to a neighboring villages. Or don’t go to school at all. To date, buildOn has built 1,323 schools internationally. buildon.org/what-we-do/global

Committee for Children

Committee for Children is a non-profit on a mission to ensure children everywhere can thrive emotionally, socially, and academically. Best known for its innovative social-emotional learning (SEL) curricula that blend research and rigor with intuitive program design, Committee for Children empowers children and their adults with skills that help them realize their goals in the classroom and throughout their lives. Since 1979, the organization has been connecting experts in the field to share experiences and advance the cause of educating the whole child. A force in advocacy, Committee for Children is helping pass policies and legislation that place importance on creating safe and supportive learning environments. Today its programs reach more than 15 million children in over 70 countries worldwide—by lifting up children today, Committee for Children is helping them create a safe and positive society for the future. cfchildren.org

InformEd

InformEd International works to create sustainable solutions to the toughest education challenges through data-driven consulting services and market-based programs. The organization supports non-profit organizations and businesses operating in the international education sector to strengthen their social impact through evaluations, operational research, strategy design, and data systems that enable achievement of organizational and project objectives. Furthermore, InformEd’s program designs aim to change the world by thinking outside-the-box, creating business opportunities that improve social wellbeing. Currently InformEd is using a Developmental Evaluation approach to drive the creation of a School Leadership and Management program with Save the Children. InformEd is also building monitoring and evaluation systems for organizations like World Vision and Amplio, bringing data to life through interactive data visualizations. The team is excited about upcoming opportunities to improve numeracy outcomes and strengthen the global book supply chain. informedinternational.org.

Mercy Corps

Mercy Corps helps young people and adults access education in the face of war, poverty or other crises. Last year the organization supported more than 237,000 people access quality education and helped reconstruct or build more than 320 schools around the world. For example, Mercy Corps provides education and skills building training to children and teens living in conflict zones in Colombia. Through after school programs, investments in teacher training and increased involvement of parents in students’ academic life, Mercy Corps’ program contributed to an over 30 percent improvement in mathematics and language among student participants. mercycorps.org

Mission Africa

Mission Africa believes that education is the key to ending generational poverty and that investment in education can have a profound impact on communities. Many African countries do not offer free education and Mission Africa is dedicated to ensuring that all children regardless of their income level have access to quality education. In the past ten years, Mission Africa’s academic scholarship program has awarded 795 scholarships and has allowed more than 300 students in rural villages in Nigeria, Tanzania, Kenya, Sierra Leone, Togo, Rwanda and Uganda to graduate high school and continue on to college or vocational training. Mission Africa has also shipped ten 40-foot containers filled with books and school supplies to children and families in Nigeria, Kenya and Tanzania. missionafrica.us

Mona Foundation

Since its founding in 1999, Mona Foundation has had a simple but compelling goal — to support grassroots educational initiatives that build stronger and more sustainable communities and ultimately alleviate poverty. Mona partners with organizations that work to reduce the barriers to education, improve quality of learning and cultivate agency of the individual. The foundation’s programs use an integrated approach to develop academic skills, and creative and moral capabilities, to transform young people into agents of change in service to their families and communities. Mona Foundation has awarded more than $12 million to 38 initiatives in 18 countries, providing access to quality education and training for more than 258,000 students, teachers and parents annually. monafoundation.org

The Northwest School

The Northwest School in Seattle is an independent 6-12 school that strives to develop active informed citizens who understand the complex interconnections that characterize our most urgent challenges, both locally and globally. Through intentional curriculum and programs, students develop social justice awareness, environmental stewardship, and global perspective, and come to understand the critical intersection between these three. The Humanities curriculum emphasizes literature by developing world writers, people of color, and women. Seniors engage in college-style seminars examining literature, history, and world politics through equity and social justice lenses. The Environment Program requires students to clean the buildings and school grounds, as well as recycle and compost, while the student-led Environmental Interest Group maintains the school’s urban farm/garden. Domestic students learn alongside 50-80 international students in the boarding program. Students also participate in three annual trips abroad to China, Taiwan, France, Ethiopia, Spain, and El Salvador, and immerse in six-week study-abroad opportunities in France, Spain, China, and Taiwan. northwestschool.org

NPH USA

NPH USA supports Nuestros Pequeños Hermanos (Spanish for “Our Little Brothers and Sisters”) which is raising more than 3,400 orphaned, abandoned and disadvantaged boys and girls in Bolivia, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua and Peru. NPH believes that a quality education is the key to a better life. Many children arrive at NPH with little or no formal schooling. Each child is given a strong foundation of basic academic and interpersonal skills and provided with an extensive variety of educational opportunities. Nearly all of NPH homes feature on-site schools from Montessori preschool through middle or high school, as well as vocational trade certification courses. In 2015, NPH supported 369 students in university – the most in the organization’s history. An additional 2,100 children who live in low-income areas outside the homes receive scholarships to attend NPH schools. nphusa.org

Rwanda Girls Initiative

Rwanda Girls Initiative’s mission is to educate and empower girls in Rwanda to reach their highest potential. The organization strives to cultivate inspired leaders with a love of learning and a sense of economic empowerment to strengthen their communities and foster Rwanda’s growth. The Gashora Girls Academy of Science and Technology (GGAST) was opened in 2011 as an innovative and socio-economically diverse model upper-secondary school, designed to provide a “whole girl” education. GGAST provides a rigorous college prep academic program, combined with leadership training and extra-curricular activities that fill girls with confidence that they can pursue their dreams of university education and fulfilling and impactful vocations. rwandagirlsinitiative.org

Sahar

Sahar’s mission is to create educational opportunities in Afghanistan that empower and inspire children and their families to build peaceful, thriving communities. Sahar achieves its mission by partnering with the Afghan Ministry of Education and Afghan-based organizations to build schools and design educational programs that address the key barriers to accessing and completing education for girls. Sahar’s programs include a unique Early Marriage Prevention program, designed to encourage girls to delay marriage and stay in school; teacher training courses that provide jobs to young women, while simultaneously decreasing the lack of female teachers that keep many girls out of school; coding classes; and much more. Currently, Sahar is raising funds to build the first public boarding school for girls in Afghanistan, providing a safe option for rural girls to receive their education. sahareducation.org.

Schools for Salone

Schools for Salone is a non-profit that revitalizes Sierra Leonean communities, empowers children and improves socioeconomic conditions for families, communities and future generations. The organization improves access to and quality of education, and has built 18 schools and three libraries since 2005. Schools for Salone also trains teachers at intensive summer institutes. With a proven track record of working with Sierra Leoneans as they rebuild after a ten-year civil war, the organization builds new schools within three months after funds are raised. Through opportunities that only an education can provide, Schools for Salone strives to break the cycle of poverty, one school at a time. schoolsforsalone.org

Spreeha

Spreeha empowers underprivileged people by providing healthcare, education, and skills training. Spreeha’s work in the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh builds on its core values of empathy, creativity, lean methodology, continuous learning, and partnership. The objective is to create longer term positive changes like healthcare and education for women and children. In most cases, those being served are pregnant and rape victims or children who have been orphaned. Spreeha’s early childhood development centers aim to create a safe and supportive learning environment for the refugee children with pre-school education. Spreeha strives to create lasting impacts on the lives of those who are in the most difficult of situations. spreeha.org

The Spring Development Initiative

The Spring Development Initiative (TSDI) is a Redmond-based global non-profit that supports aspiring African leaders working towards positive social change. TSDI provides training, collaboration and investment to self-employed and early career professionals, with the aim of fostering new and innovative business and non-profit ideas and models that will lead to sustainable development. As part of its work, TSDI recruits experienced mentors and encourages a positive work ethic for future careers in policy making, business, governance, etc. TSDI is currently working with SI4DEV, a local organization in Nigeria, to provide two programs aimed at establishing quality education, entrepreneurship, sustainable lifestyles, gender equality, peace and cultural diversity among local communities. The Life Skills project reaches students 10 to 19 years old, and encourages self-reliance, resilience and employability. The Street Business School project trains youth and women living in urban-poor communities how to increase their income by building and scaling sustainable businesses. sid-initiative.org

Back to Top

Partnership Highlights

Data Visualization Prompts Deeper Questions about the Effectiveness of Early Grade Education Intervention

By Lisa Zook & Cameron Ryall

Data visualizations by Billi Shaner

Mphatso, 8, a Grade 3 student in the World Vision Malawi Literacy Boost program.

Photo credit: World Vision Malawi

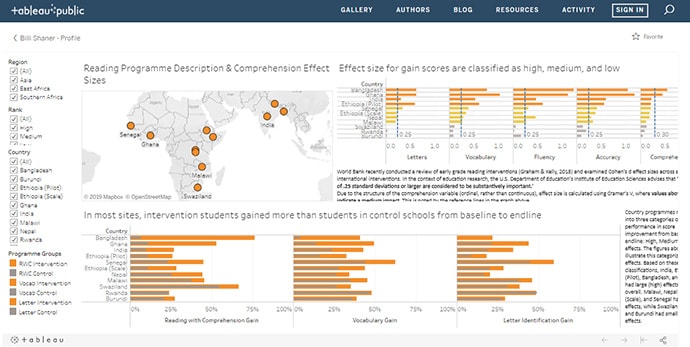

More than half of children globally do not meet minimum proficiency standards in reading and mathematics. InformEd International and World Vision are re-examining data collected in their work to improve early grade reading outcomes using Tableau’s data visualization software. This has enabled greater insights into the early grade education programming’s effectiveness, as well as demonstrated where there is room for improvement.

From 2012 to 2017, World Vision International, in partnership with Save the Children, implemented an early grade reading program called “Literacy Boost” in ten countries throughout Africa and South Asia. The goal was to equip schools, parents, and communities to support children’s literacy from kindergarten through third grade. As part of each country’s program, World Vision coordinated randomized-controlled trials to determine the program’s impact. This provided a unique opportunity to examine the impact across a variety of contexts.

After 2017, World Vision had a series of rich datasets from each project site and a set of country-specific reports. At a global level, however, it was challenging to make sense of the disparate reports. Students in the intervention schools generally outperformed students in comparison schools, but questions remained: At what point is a program considered a success? What led to different results in different countries? Should certain programs be taken to scale, and if so, when?

In order to answer these questions, InformEd analyzed the reading outcomes from each country’s dataset, and compared them against student benchmarking standards from the World Bank.

As part of the reporting process, InformEd used Tableau data visualization software to create a dashboard and an accompanying story summarizing the results. The story provides an overview of the conclusions drawn from the research, while the dashboard allows for sub-group filtering of the results (by country, region, and by effect size rank). Both resources led to greater engagement with findings than a traditional report and sparked important discussions among program staff. (Explore the dashboard and story here).

Eight of the eleven implementation sites exhibited effect sizes that surpassed the World Bank’s benchmark for a significant gain in educational outcomes. In the four countries with particularly strong effect (Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Ghana, and India), students received the equivalent of an additional year of learning as a result of the Literacy Boost program. The other three sites saw significant differences in children’s reading performance between intervention and control, but only small effect sizes.

Most importantly, in viewing the data in this way, InformEd found that a project’s performance was falling into one of three categories: high, medium, or low. The performance classification held across learning outcomes, showing that Literacy Boost doesn’t only impact struggling students or strong students, but rather has a positive impact on children along the entire path to becoming a reader.

Students in reading camps make reading materials in World Vision India’s Literacy Boost program.

Photo credit: Max Greenstein / World Vision

Identifying these trends sparked new questions for those working on the project. Firstly, how did program implementation differ across the three categories of performance? To answer this question, InformEd has worked with World Vision to develop a suite of electronic data collection tools to monitor program implementation and uptake. Data from the monitoring activities is then uploaded and visualized in real-time, empowering program staff to identify communities or technical areas needing additional support. (View the monitoring system here).

Furthermore, the teams want to investigate if certain variables enable the program to achieve greater results. For those countries that observed large effect sizes, what makes them different from those that didn’t meet the World Bank threshold? Were children at a different starting point? Or were some schools and teachers more active in program activities or more likely to adopt behaviour change? If so, why? If there are certain characteristics identified, perhaps the Literacy Boost approach needs to be adapted for certain challenges, contexts, or settings. These findings can also contribute to global dialogue on effective practices to support achievement of SDG 4.

Deeper analyses of existing data are leading to important advancements in our discussions about and our knowledge of how best to address the learning crisis. We’re hopeful that we are getting closer to knowing what works where so that we better address the unique needs of each child and, ultimately, ensure that all children are receiving quality education.

Back to Top

Organization Profile

Ashesi University Foundation: Ashesi University is Shaping Africa’s Future Leaders

By Joanne Lu

Students walk across the Ashesi University campus. Photo provided by Ashesi University Foundation.

“Whatever you can do or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, power and magic in it. Begin it now.”

These words from German philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe are engraved on the glass doors of the entrance to Ashesi University in Accra, Ghana. When the university’s founder, Patrick Awuah, quit Microsoft to pursue his vision of educating Africa’s future ethical and entrepreneurial leaders, Goethe’s exhortation offered him the reassurance he needed. It also inspired the name of his school: Ashesi means “beginning” in Asante.

For Awuah, the beginning of Ashesi’s story goes back to his own college education at Swarthmore. Even as an engineering student, he was studying subjects like political science, history, and economics, and gaining an understanding of the context in which innovation and industrialization happens. The liberal arts approach was different from any educational model he’d seen at home in Ghana.

The longer Awuah spent in the States, the more determined he was to stay. He enjoyed living here, loved his work, and was frustrated with Ghana’s lackluster development. But things shifted with the birth of his first child. Suddenly, Awuah realized that the future of Africa was important for his children and his grandchildren, and to honor their ancestry and legacy, he had to be a part of helping Ghana thrive.

Awuah’s initial instinct was to start a software company – after all, he worked for Microsoft. But the more he researched and talked with others, the more he realized that a lack of visionary leadership is what continued to hold back Ghana from thriving.

That’s when Awuah turned his focus to starting a university. Although less than 10 percent of Ghanaian youth at the time were attending university, Awuah knew that the leadership of the future would likely come from that small base. Therefore, he wanted to give them the tools they needed to lead differently – to lead ethically and effectively.

“If we can help our students discover who they are and understand where they stand in society and the responsibility that they have to their society, we will have achieved a great deal,” says Awuah.

Patrick Awuah, founder of Ashesi University. Photo provided by Ashesi University Foundation.

Awuah launched Ashesi University in 2002 with 30 students. Today, there are 1,013 students from more than 20 countries, and by 2020, they expect to have 1,200 students. Currently, 17 percent of the student body is international students, and eventually, Ashesi aims to make that 30 percent. But no more than 10 percent will ever be from outside Africa, because the goal is to invest in African students as the continent’s future leaders.

Currently, Ashesi offers four majors that were designed in response to what’s needed in the workforce: management information systems, computer science, business, and engineering. But, like Awuah’s own Swarthmore education, these technical majors are based on a liberal arts curriculum that equips students to navigate the context in which they will innovate and solve problems. It’s not just about offering a well-rounded curriculum. Ashesi’s curriculum is designed to complement technical skills with a holistic understanding of African history, society and the world at large in order to instill in students critical and entrepreneurial thinking.

By entrepreneurial thinking, Ashesi doesn’t just mean starting and running businesses (although, it does encourage students to do that, too). Ashesi defines entrepreneurial thinking as identifying and solving problems – something that’s not commonly taught in African schools, where students are often trained to spit back one particular answer and adhere to one way of doing things. Perhaps that’s why leaders on the continent have for so long been able to perpetuate power imbalances and poverty, despite local and international investments, natural resources and economic resources, says Megan MacDonald, Director of Strategic Partnerships at Ashesi University Foundation.

MacDonald also notes that in a context of poverty, human instinct is to take for oneself when one gains access to resources. But especially with Africa’s booming population growth and the added challenges of post-colonialism, the continent needs leaders who are looking at the bigger picture and who are capable of making choices for the wellbeing of everyone.

Students in class at Ashesi University. Photo provided by Ashesi University Foundation.

It is not enough just to tell students they should adhere to a certain set of values. They need to have the tools to put those values into practice. That’s why Ashesi’s approach gives students the tools and the practice they need to make different choices, to show by example that it is possible to lead ethically and dismantle systems of corruption.

And they’re doing just that. Hannan Yaro Boforo from the class of 2010 developed an AI-powered biometric coding system (thumbprint technology) that was used in Ghana’s 2012 presidential elections to help increase voter turnout and fight voter fraud. Now, he and his team are helping to implement similar technology in other African countries and other sectors, including healthcare and social intervention programs.

Kpetermeni Siakor from the class of 2015 was still a student at Ashesi when the Ebola outbreak devastated his home country of Liberia. From Ashesi’s campus in Ghana, he reached out to a non-profit in Liberia and ended up partnering with the government to create deployment tools for health workers all over the country, tracking their movements and the distribution of support. So, even while he was a student, he found a way to impact an entire country’s response to one of the deadliest outbreaks in history.

That’s why MacDonald says Ashesi has become a symbol of possibility for Africa, and why Ghanaians at home and abroad have called Ashesi “the pride of Ghana.” Beyond expanding their own scope in the future – with graduate degrees and more research capacities being considered – Ashesi hopes to continue to inspire new and existing institutions. Already, MacDonald says that some local universities in Ghana have begun to adopt a more liberal arts approach, while a new university in francophone Niger – Africa Development University – cites Ashesi as a founding model. Ashesi also runs an “Education Collaborative,” which brings together universities from across the continent – last year, it was 24 – to share best practices, troubleshoot and create an active network of institutions, committed to elevating higher education in Africa.

“In international development, there are so many external solutions to local problems,” says MacDonald. “But the whole ethos of Ashesi is that in order to solve Africa’s problems, we need to equip African leaders. I think that is really powerful, and the best thing that those of us from the international development community can do is to invest and support that leadership.”

Back to Top

Goalmaker

Mahnaz Javid: President & CEO, Mona Foundation

By Amber Cortes

Mahnaz Javid poses with a student at The Association for Cohesive Development of the Amazon (ADCAM), located in Manaus, the capital city of the State of Amazonas, Brazil. Since 2006, Mona Foundation has supported the project with scholarships and funds for capital improvement. Photo provided by Mahnaz Javid.

“Mahnaz, do not forget”

An unforgettable cab ride at a young age became a defining moment in the life of Mahnaz Javid. Growing up in Tehran, the capitol of Iran, Javid had what she described as a comfortable childhood in a “regular middle-class family.”

“When I was 12 years old, I was restless! So, my mother decided, as a way of managing my energy, to take me for a cab ride,” Javid explains. “So, we left the nice tree-lined streets of our block towards the southern part of the city, where I knew, even at that time, that this was where the poor people lived. It’s where the slums were.”

Javid remembers the rain that day, how it poured down and began washing away people’s makeshift homes right in front of her eyes.

“So, we went around for about half an hour and returned home. And I was just absolutely stunned, you know, just stunned by what I saw. And before we got out of the cab, my mother looked at me and said, ‘Mahnaz, do not forget.’”

She didn’t. “I think it just imprinted in my subconscious from then on, all the way to when I started Mona.”

“Without a moral compass, no development can happen”

Javid started the Mona Foundation in 1999 in order to provide education to all children, to empower girls, in particular, and enable them to transform their own communities.

A set of universal principles informs much of the work she does in the Mona Foundation. These principles are Baha’i inspired but equally shared by people of all traditions. For example, the principles of universal education and equality helped guide their model of philanthropy to be community-first.

“We do not import our ideas from here to there,” Javid says. “We find grassroots, local organizations to support, and empower them to lead their own development. Why? Because we believe that they are equally capable of developing their own communities.”

The Mona Foundation believes that access to education, along with gender equity, are key to alleviating global poverty (and The World Bank agrees). Though promoting education for all is important, since the global gender gap in education is so severe, the Mona Foundation focuses much of its efforts on educating girls and women.

“We know that women are at the core of development,” Javid says. “When you educate a woman, you positively impact health, you reduce hunger, you benefit families, you increase productivity, and you promote a sustainable environment.”

For Javid, the foundation to any education lives within a less material, more value-based and spiritual kind of development. She is quick to point out that what she means by “spiritual” is not necessarily religious. The basic questions about the nature of human existence—Why are here? How do we find meaning in our lives?—all form a basis for inquiry that transcends an individual’s religious beliefs and can shape a person’s ethical framework—a moral compass to guide one through life.

“Without a moral compass, no development can happen,” Javid says. “Without a moral compass, you only look at your own self-interest. You do not look after the interest of your community, of your family, of your extended family, of your nation.”

At the Mona Foundation, laying the groundwork for this moral compass starts early, by supporting programs that focus on creating sustainable development through teaching youth global citizenship. For example, supporting scholarships at the Badi School in Panama, which emphasizes moral leadership training and developing values such as integrity, trustworthiness, patience, teamwork, respect for others, and community service. There are also Global Citizenship Clubs, formed by students themselves, to help inform the worldview of the children and their place in it, and training them to provide service to the community.

For Javid, a holistic, well-rounded education means more than just teaching business and finance skills. The Mona Foundation’s philosophy of education is multi-faceted—it includes supporting fine arts, music, and creative-thinking programs in places like the Zunuzi school in Haiti and the Barli Institute in India.

Mahnaz Javid poses with students and faculty of the Zunuzi school in Haiti.

Photo provided by Mahnaz Javid.

These values align with one aspect of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal for education (SDG 4, Target 4.7), which seeks to ensure learners move into the future with “knowledge of human rights, gender equality…global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development”

Development, Javid says, should never be tied solely to just economics.

“So, if you are a “developed” nation – if you’re not hungry, if you have access to health care, clean water, electricity – these are all required and necessary indicators of development. But if men and women are not equal in that nation, what sort of development is that? Yes, you can build schools. But if girls cannot go to school, what do you have?”

“We can only make a difference together”

As Javid and others at the Mona Foundation celebrate the first twenty years of their existence, their impact continues to be wide reaching. In 2018, the programs they supported directly served over 400,000 students, parents, teachers, and schools. Over one million people have benefited from extension programs that the schools offer, like health clinics and empowerment programs.

While Javid says that alleviating global poverty through education is the ultimate goal, individuals transforming their own communities, one at a time, is what causes the real ripple effect of sustained change.

“If you look at the projects that we have supported over the years, they have all resulted in community transformation. So, it isn’t about just educating girls to us, say at Barli Institute in India. It is about educating those girls to go and transform the hearts and minds of their own village around the question of equality.”

Javid sees the Mona Foundation continuing to thrive in the future—but not without the help of the forward-thinking schools and organizations in their network.

“If Mona worked from now until the end of the world, we would not be able to make a dent in the way that things are all by ourselves,” she says. “I think that we can only make a difference together, in partnership with our adopted local organizations who are doing the actual work of development in the field, and by sharing our learnings with like-minded organizations who are supporting these and other similar initiatives. Together, we are confident that we can address the root causes of poverty through education and gender equality and can create a world where no child ever goes to bed hungry, is lost to preventable diseases, or is deprived of the gift of education.

Back to Top

Welcome New Members

Please welcome our newest Global Washington members. Take a moment to familiarize yourself with their work and consider opportunities for support and collaboration!

RISE BEYOND THE REEF

Rise Beyond the Reef bridges the divide between rural remote indigenous Fijian communities and the outside world, promoting women as leaders of their communities on the frontlines of climate justice. risebeyondthereef.org

Back to Top

Member Events

August 13-14: Amazon // Imagine Conference

August 29: Seattle International Foundation // Crisis & Migration: A Conversation with Central American Independent Media

October 24: Sahar // Fall Fundraiser

November 21: BuildOn // Gala

Back to Top

Career Center

Communications Assistant, Amplio

Manager of Student Programs, FIUTS

Executive Assistant, Essential Medicines, PATH

Check out the GlobalWA Job Board for the latest openings.

Back to Top

GlobalWA Events

August 22: Networking Happy Hour with GlobalWA, WGHA, & World Affairs Council

September 5: The Fast Funding Fundamentals

September 13 A Conversation with Feminist Rukhshanda Naz from Pakistan

New Date November 15: GlobalWA Goalmakers Conference

Back to Top

Intersectionality for Inclusivity: Recognizing the Human Rights of Every Human

Posted on August 5, 2019.

By Anna Pickett and Josué Torres

Introduction

In the context of global development, disability is too often ignored or rendered invisible. Organizations that work to promote equity often times don’t support disabled populations because disability is not one of their focus areas, or because they have other priorities. But the truth of the matter is, if an organization works on human rights without including people with disabilities, they are only really promoting the rights of some humans.

With this work, applying an intersectional approach allows for a deeper and more nuanced understanding of how social identities and conditions interact within a society. As a result, we gain a broader picture of human diversity. In discussing inclusion in global development and improving the standards for living a life of dignity, we must understand the concept of intersectionality and have the awareness that disability is a human condition that is present in a significant percentage of the global population. According to the World Bank, one billion people, or 15% of the world’s population, experience some form of disability.

Continue Reading

Event Recap: Disability Inclusive Development Initiative Workshop

Posted on August 5, 2019.

By Kara Eagens

In June, Global Washington hosted members of the Disability Inclusive Development Initiative (DIDI) to introduce best practices for disability inclusion in international development.

DIDI is a multidisciplinary research and advocacy project at the International Policy Institute of the University of Washington’s Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies. Comprised of graduate and undergraduate students, DIDI works to support the inclusion of persons with disabilities in development.

Stephen Meyers, a professor of disability studies and international studies at the University of Washington, opened the event with remarks on the realities of disability inclusion within the international development sphere.

Continue Reading

EVENT RECAP: Roundtable with Michelle Nunn, CARE USA President and CEO

Ending Violence Against Women

By Peachie Ann Aquino

CARE USA President and CEO, Michelle Nunn (second from left) is joined by CARE colleagues at Global Washington for a roundtable discussion on ending violence against women.

(Photo: Peachie Ann Aquino for GlobalWA).

“Achieving real equality for women and eradicating gender-based violence can transform the world in many ways” stressed Michelle Nunn, President and CEO of CARE USA. “The highest and most powerful good that we can do is to invest in local women’s grassroots movements who are creating social and societal change”

Continue Reading

July 2019 Newsletter

Welcome to the July 2019 issue of the Global Washington newsletter.

IN THIS ISSUE

Letter from our Executive Director

We all want a better life for our families and for ourselves. I’d go so far as to say the impulse to improve our lot in life is pretty much universal. When people can no longer bear the conditions in which they live, when they can no longer count on being able to take care of the ones they love, they are willing to do whatever it takes to change those circumstances. Human traffickers look for desperate people like these. Promising them work and a better life, they lure them into some of the most horrific working conditions imaginable. According to the UN, the majority of detected trafficking victims globally are women and girls, most of whom are trafficked for sexual exploitation.

Our newsletter this month explores the terrifying reality of human trafficking in developing countries and some of the ways that organizations and individuals are fighting back. Our Goalmaker this month, Veronica Fynn Bruey, an affiliated faculty member at Seattle University School of Law, escaped the civil war in Liberia to become an award-winning scholar in law, public health, science and psychology, as well as an advocate for displaced and trafficked persons globally. Our featured member organization, Every Woman Treaty, is campaigning to establish a global treaty to end violence against women and girls.

Also, I’m excited to announce that registration for our annual conference in Seattle on December 5th is now open. The conference sold out last year, so if you know you plan to be there, take advantage of Early Bird pricing and purchase your tickets today.

Kristen Dailey

Executive Director

Back to Top

Issue Brief

What Will It Take to End Modern Slavery?

By Joanne Lu

A former fishing boat slave profiled in the new film, Ghost Fleet.

Photo courtesy Vulcan Productions.

We often think of slavery as a scourge of the past, something that developed countries, at least, abolished centuries ago. But devastatingly, slavery continues to thrive around the world, in both rich and poor countries – so much so that it is addressed in three of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for 2030. Today, we call it human trafficking.

Although the term often evokes the idea of victims being smuggled across borders, human trafficking is much more than that. It is the exploitation of people – usually girls and women – through force, fraud or coercion for labor, sex, marriage, organ removal, illegal adoption, begging or other purposes.

In January, the UN’s Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) said that the number of trafficking victims being reported by countries is increasing. However, it’s difficult for the agency to say if that trend reflects an actual increase in victims or if countries are just doing a better job at detecting and reporting them. Either way, we are far from a complete and accurate picture of the global scale of trafficking, but what we do know is bleak.

The latest UN estimate says that at any given time in 2016, there were 40.3 million victims of human trafficking around the world. In other words, more people than are in the entire state of California are being subjected to modern slavery, including nearly 25 million people in forced labor and 15.4 million in forced marriages.

The UNODC report says that the vast majority of detected trafficking victims – 72 percent – are women and girls, most of whom are being trafficked for sexual exploitation. However, 35 percent of victims who are trafficked for forced labor are also female. That’s why SDG 5, which aims to “achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls,” includes as Target 2 to “eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation.”

Although trafficking is a global problem, the predominant forms of exploitation and profiles of victims vary by region. In East Asia and the Pacific, both women and girls are primary targets for sexual exploitation. In North America, South America, Western and Southern Europe as well as Central and Southeastern Europe, adult women face the highest risk of sexual exploitation, while in Central America, it’s girls.

Women are also primarily targeted for sexual exploitation in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, but there, men are prime targets for forced labor, as well. In the Middle East, East Africa and Southern Africa, men and women are both targeted for forced labor. But in West Africa, children are the main victims of trafficking for forced labor.

Men, women, girls and boys are all at high risk of being trafficked in South Asia. For men, it’s mostly for forced labor, while for women and children it’s for both labor and sexual exploitation. Similarly, in North Africa, adults and children of both genders are targeted by traffickers, but there, it’s primarily for begging, organ removal and other forms of exploitation.

According to the UNODC, most trafficking victims are detected in their home country. However, the highest number of victims detected outside their home region are from East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. On the receiving end, wealthy countries – especially in Western and Southern Europe and the Middle East – have the largest shares of trafficking victims from other regions.

So, what’s driving this global epidemic? In many cases, traffickers capitalize on potential victims’ desire to migrate for better conditions. Increasingly, that desire is driven by conflicts, which have destabilized governments, threatened the physical safety of civilians, eliminated economic opportunities and pushed many families into poverty and hunger. Weak rule of law and depleted resources create ideal environments in which traffickers can prey on desperate people.

But trafficking is also a lucrative operation. In 2014, the International Labour Organization (ILO) reported that forced labor generates $150 billion in illegal profits every year. Two-thirds of that is from commercial sexual exploitation, while the rest is from other forms of economic exploitation. Of those, construction, manufacturing, mining and utilities industries profited the most ($34 billion), followed by agriculture, forestry and fishing ($9 billion) and domestic labor ($8 billion).

Vulcan Productions – a film company founded by Microsoft’s co-founder Paul G. Allen and his sister, Jody Allen – recently brought to audiences the appalling realities of the modern slave industry. Their documentary, “Ghost Fleet,” follows Thai activist, Patima Tungpuchayakul, and her husband, Sompong Srakaew, as they risk their lives to rescue enslaved fishermen in Indonesia. Many were kidnapped from Thailand and Myanmar to “feed the world’s insatiable appetite for seafood,” including fish found in U.S. grocery stores.

Although the fishing and agriculture sectors are certainly responsible for a large share of slavery, the ILO noted in a 2017 report that, apart from sexual exploitation, domestic labor actually accounts for the largest percent (24 percent) of identified forced labor cases in the private economy. That’s because most countries do not protect domestic workers under their labor laws. Many coercive practices also occur in construction, which accounts for 18 percent of identified forced labor exploitation cases.

Perhaps the sector that has received the most attention for forced labor practices is manufacturing, where 15 percent of identified cases occur. In particular, small garment and footwear factories in South Asia have come under public scrutiny, as have electronics brands. But forced labor is also prevalent in many other forms of manufacturing that haven’t received as much attention, such as medical garment factories in Asia that rely on migrant workers or technology companies that use minerals in their products mined from conflict zones.

But most companies don’t even know if slave labor is a part of their products’ supply chains. That’s why organizations like Made in a Free World have decided to catalyze large-scale change with tools to promote transparency. Their software platform, FRDM (pronounced freedom), is a global database that helps companies map their supply chains to make sure they’re in compliance with national and international regulations on human trafficking and child labor.

Certainly, companies and consumers have a responsibility to exercise due diligence, but governments and the international community also play a critical role in tackling this gross human rights problem. That’s why Target 7 of SDG 8, which promotes “decent work for all,” calls on countries to “take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labor, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labor, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labor in all its forms.”

One step toward doing that is captured by SDG 16, which aims to “promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.” Well-functioning institutions are absolutely necessary for detecting human trafficking victims, reporting cases and convicting perpetrators. Target 2 of the goal calls specifically for an “end [to] abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children.”

According to UNODC, there has been a significant improvement in countries’ capacities to detect and report trafficking cases. Ten years ago, only 26 countries had an institution that systematically collected and shared data on trafficking. By 2018, 65 countries had such an institution. Still, major gaps in data collection and reporting persist.

In many countries, exploitation goes unreported because victims don’t know how to take legal action against their abusers. The World Justice Project launched the SASANE Paralegal Training Program in Nepal, in order to address that issue. The program, led by survivors, trained trafficking survivors to become paralegals, not only to help them gain financial independence, but also to equip them to help other survivors.

Overall, UNODC says that conviction rates have increased as the number of detected and reported victims have increased. This means that criminal justice systems are working. But many countries, particularly in Africa and Asia, still have very low numbers of convictions, as well as fewer detected victims. These figures suggest an environment of impunity that, if left unaddressed, could incentivize more trafficking.

That’s why it’s so important for the entire global community to work toward sustainable development on all fronts. Abolishing modern slavery not only requires tackling the issues that make people vulnerable to exploitation, but also building a world in which trafficking cannot continue.

* * *

The following Global Washington members are working to end human trafficking.

Every Woman Treaty

Every Woman Treaty is a coalition of more than 1,700 women’s rights activists, including 840 organizations, in 128 nations working to advance a global binding norm on the elimination of violence against women and girls. The organization’s working group studied recommendations from the United Nations, the World Health Organization, and scholarly research on how to solve the problem of violence against women and girls, including trafficking and modern slavery, and found that a global treaty is the most powerful step the international community can take to address an issue of this magnitude. Learn more, sign, and support at everywoman.org.

International Rescue Committee – Seattle

The International Rescue Committee’s anti-trafficking programs strive to provide timely, high-quality, comprehensive services to survivors of human trafficking. The IRC also works to improve the community response to survivors of trafficking by providing training to local service providers and allied professionals and working to enhance collaboration and coordination among multi-disciplinary professionals on behalf of survivors of human trafficking. The IRC’s goal is to help survivors build lives for themselves that are free from abuse and exploitation. rescue.org/united-states/seattle-wa

Resonance

Resonance is an international development consultancy focused on igniting opportunity in emerging markets. The firm works with companies, NGOs, finance institutions, and international donors to develop new business models and innovative partnerships that improve governance and sustainability outcomes. As part of our work across a number of sectors, Resonance has extensive experience creating shared value public-private partnerships to combat trafficking and reduce supply chain vulnerability. We are currently engaged with USAID on Counter Trafficking in Persons (CTIP) projects in Thailand and across Southeast Asia to address forced labor in the seafood, agriculture, construction, and domestic work sectors. Resonance also supports multinational corporations in their promotion of technologies that enable worker voice, enforcement of fair labor practices, and reduction of incentives for trafficking in their supply chains. resonanceglobal.com

World Justice Project

The World Justice Project (WJP) is an independent, multidisciplinary organization working to advance the rule of law worldwide. Effective rule of law reduces corruption, combats poverty and disease, and protects people from injustices large and small. It is the foundation for communities of justice, opportunity, and peace—underpinning development, accountable government, and respect for fundamental rights. In addition to its research and data initiatives, WJP engages its global network to foster and support locally-led programs that strengthen the rule of law. Seed grants from WJP have supported programs like SASANE Paralegal Training for Trafficking Survivors in Nepal, which places certified paralegals in local police stations to provide frontline assistance for trafficking survivors. And in Kyrgyzstan, WJP recently supported a young lawyer working to end the practice of kidnapping girls for forced marriages. worldjusticeproject.org

Back to Top

Organization Profile

Could a New Global Treaty End Violence Against Women and Girls?

By Joanne Lu

What would happen if every country in the world were legally bound by a comprehensive international treaty against all forms of violence against women and girls? The Every Woman Treaty intends to find out.

The project was launched in 2013 under the name “Everywoman Everywhere” by a global group of women’s rights activists, who determined that there is a large gap in international law regarding the protection of women and girls.

Certainly, the United Nations’ (UN) 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, 1993 Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women and 2000 Convention against Transnational Organized Crime have all pushed the conversation forward in important and significant ways. But amid the limitations of those existing declarations and conventions, the group saw the urgent need for a legally binding global treaty that holds countries accountable for all forms of violence against women.

Since its launch, the effort has blossomed in a very grassroots fashion into a coalition of more than 1,700 women’s rights advocates and experts, including 840 organizations, in 128 countries.

“I was sold straight away,” says Laurie Tannous, who joined Every Woman Treaty’s Global Working Group in 2016 and serves on their special expert committee on human trafficking. At the time, Tannous – an international business and Canadian immigration attorney – was attending conferences and giving speeches on trafficking, when a new friend introduced her to the Treaty.

“A treaty is a call to action – a collective one,” says Tannous. “And if you have this collective international voice being driven by one document, it keeps things very efficient and powerful.”

Tannous says that when she first got involved, trafficking and modern slavery weren’t yet a major part of the Treaty. Although she is, of course, opposed to violence against women and girls, her work centers on preventing women, children and even men from being smuggled across borders and enslaved.

The group responded to her concerns with what she now recognizes as their emblematic commitment to inclusivity: “Let’s include that, too.”

Today, the group has drafted a “zero draft” or core platform—the framework nations will use to draft the official treaty. The draft has been sent to 2,000 experts for peer-review, and it addresses all types of violence against women, including domestic violence, non-state torture, state-sponsored violence, and workplace violence, as well as trafficking and slavery. It also considers four groups of vulnerable women and girls, three life stages (girls and students, older women and widows of all ages) and specific actionable recommendations for preventing, suppressing and punishing violence against women and girls, including trafficking in persons.

For example, some countries still punish survivors and victims of trafficking and slavery (like sex slaves who are punished for prostitution). This discourages victims from reporting incidents of trafficking, which is absolutely necessary data if countries and municipalities are to work toward eradicating it. The group is aiming for a treaty that prohibits the punishment of survivors and victims, with the hope that in doing so, they would feel safer telling their schools, neighbors, police officers or nurses about the crimes that had been committed against them. Increasing this first level of reporting is a critical first step in tackling the problem.

But in addition to laying out enforceable protocols, Tannous says the goal is also to increase awareness, outreach, and education of the issues and promote effective strategies for eradicating them. For example, the special expert committee on human trafficking identified a huge gap in countries’ understanding of the definition of trafficking. A “lack of clarity in definitions leads to problems in prosecuting violations,” they wrote in their policy memo. In this way, Tannous says, the Treaty is meant to enhance existing UN conventions.

“We can create law all day long, but if it’s not enforced, if it’s not adopted, if it’s not supported, if it’s not talked about – it’s as good as the paper it’s written on, and nothing more,” says Tannous.

At the moment, the Treaty is still in development, as experts review the draft and leaders of the group meet with potential “lead nations,” who will commit to signing the Treaty and serve as its ambassadors. These lead nations will be the ones who bring the Treaty to the UN for adoption by all member states.

The challenge moving forward, according to Tannous, is getting countries to understand that a global treaty to prevent violence against women and girls is not redundant, but rather is a necessary step to closing loopholes in existing international laws and instruments. But once that is clear, she believes the grassroots commitment that launched this effort to begin with will be the same force that keeps the momentum going.

“Just look at the sheer number of women who have taken their own time to contribute to this effort,” she says. “None of us get paid for this, but we’re so personally vested in it that I think everyone intends to see it through – that OK’s mean action.”

If countries translate their commitments into action, then the Treaty could become the catalyst for a historical change in global norms, the group says. Consider the Tobacco Treaty, which ended smoking on airplanes and in many public spaces. Indeed, with enough action, a treaty to end violence against women and girls could end not only the trafficking of women, but all forms of violence against women and girls. Now, wouldn’t that be a treaty for every woman everywhere.

Back to Top

Goalmaker

Veronica Fynn Bruey, Affiliated Faculty Member at Seattle University School of Law

By Amber Cortes

Photo provided by Veronica Fynn Bruey.

“Freedom,” Jean-Paul Satre once wrote, “is what we do with what is done to us.” Professor, lecturer, and award-winning scholar, Veronica Fynn Bruey, has faced some of the most challenging hardships one can imagine: poverty, war, displacement, racism, and violence. Through it all, she found the strength—through her mother, her own personal motivation, her community, and her work, to not only achieve success for herself, but also to help others—specifically victims of human trafficking—find the freedom and protection they deserve.

An Early Life of War and Displacement

Veronica Fynn Bruey was born in Liberia. When she was just 14, the civil war broke out there, and her family became displaced in their own country, and subject to violence and uncertainty. In July 1992, the family decided to flee to Ghana for safety.

“So yeah, that’s how we made it to Ghana. And on a deck of the Ghanaian peacekeeping vessel, three days, in the sunshine and in the rain. No food, no water until we arrived,” she explains.

While in Ghana, the family stayed in a refugee camp. However, things didn’t quite work out as planned, and in 1993, Fynn Bruey’s mother, who was sick, decided to bring the family back to Liberia, despite the ongoing conflict there. But Fynn Bruey, in what she describes as a “life-changing decision,” stayed in Ghana to pursue her education, “because my mom always said: education was the equalizer. And if we needed to make that change and escape the chain of poverty that we constantly had in our family, then I must listen to her and stay back.”

Six Degrees of Affirmation

Veronica Fynn Bruey’s hunger for education turned out to be insatiable, and it led her on her life’s path to earn not one…not two…not three…not four…not even five, but SIX academic degrees.

“People are always fascinated by how I’ve been able to acquire six university degrees given the fact that I came from a war zone,” she says, “and I lost three years of my life that I wasn’t in school, and another two years working, doing my national service in Ghana.”

She’s certainly made up for lost time. Starting in Ghana, with dreams of becoming a medical doctor, Fynn Bruey pursued an undergrad in zoology and biochemistry. But when she wasn’t accepted into the highly competitive medical school there, she didn’t fret. “I wasn’t going to waste my time and be like, without medical school, I’m doomed.”

Instead, Fynn Bruey headed to Canada to continue her education as a refugee-sponsored student, where she earned a BA from the University of British Columbia. She chose to study psychology.

“I came to Canada with a lot of trauma of abuse, I mean, both physical and sexual abuse, from my childhood, and it had haunted me a lot. So, I didn’t do psychology to help anybody else—just myself!” Fynn Bruey explains.

Soon afterwards, Bruey decided to go to England to get her Master’s in Public Health. She liked the more holistic approach of working with populations, and saw it as a better fit for her than medicine. The focus of her dissertation was on refugee mental health. “Of course, you can see where all this is going,” she says with a laugh.

Throughout her life, Fynn Bruey’s studies have been inexorably intertwined with her lived experience as a displaced person and refugee survivor of abuse who grew up with a single mother. But it wasn’t until 2003, when she was introduced by a mentor to a groundbreaking new book at the time: The Natashas: Inside the Global Sex Trade by Victor Malarek, that she encountered the term ‘human trafficking.’ It struck a chord.

“And so, I read it, and I was like, ‘Oh, this is not very much different from my experience of violence. You know, it’s not necessarily… in my case, nobody bought me or took me by force, it was some sort of coercion.” The book, she says, had a profound effect. “So, I was like, this is it for me—I’m going to explore this area, I’m going to give my all into it, because this violence has to stop!”

Fynn Bruey got shortlisted by a Government of Canada program to go to Geneva in 2006. There, she researched health and human trafficking at the International Organization for Migration, and started hanging out at the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, with hopes of using her own experience as a refugee to jump start a career working with displaced people and combating human trafficking.

“I was constantly told I needed a law degree to work there. And I just couldn’t understand! I have three university degrees, and the lived experience of being a refugee, is that not good enough? Yeah… I still needed a law degree.” So Fynn Bruey got her Master’s in Law at York University’s Osgoode Hall Law School, focusing her dissertation on the legal discrepancies between protecting refugees and internally displaced persons. Prior to her Master’s in Law, she served as a research analyst for the Government of British Columbia’s Office to Combat Trafficking in Persons.

While in the program, Fynn Bruey was encouraged to get her PhD in law as well. “My supervisor said to me, you know, you are not married, you don’t have children. This is a good opportunity to do a PhD!” Eventually, she ended up at the Australia National University (ANU). But when she started applying for teaching positions, she was told she needed yet another degree… a bachelor’s in law.

“Actually, I did it concurrently with the University of London and ANU. It nearly killed me,” she says, laughing. “But I’m somebody who you can never tell that something is impossible to do. Because I will prove to you, with this incessant and daring personality, that I can do it. Even if it costs my own death, I will do it!”

Connecting the Dots of a Clandestine Industry

Fynn Bruey’s wealth of knowledge that comes from studying over half a dozen fields around the globe deeply informs her work in human trafficking. It’s because, she says, these fields—feminism and reproductive rights, public health, migration and displacement, indigenous and race studies, systemic violence, and international law—are all linked.

A cross-disciplinary approach, Fynn Bruey says, addresses the need to see human trafficking as a complex issue. “You need to bring in the feminism aspect, you need to bring the racism aspect, you need to bring a public health aspect into it. You need to bring in patriarchy and power and control, economics and finance.”

For example, understanding psychology, systemic violence, and international law comes in handy when dealing with one aspect of human trafficking—coercion. The United Nations defines human trafficking as recruitment or harboring of people “by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion.” When people are coerced, Fynn Bruey says, they “consent” because they have no other alternative. Another part of what makes human trafficking such a difficult issue to address is its clandestine nature.

“It operates in secret. People who are vulnerable to these situations will never see the light of day; they’re locked up somewhere. Nobody knows whether they exist, or what is happening to them.”

This lack of data makes it hard to actually convict and prosecute traffickers. According to the latest 2019 Trafficking in Persons report, globally the number of new legislation passed to address human trafficking has reduced over the years, and prosecutions and convictions remain startlingly low in proportion to the number of victims reported.

Fynn Bruey says she’d rather spend years developing lasting solutions to combat human trafficking, than to simply adopt a unilateral response to the issue, which is “to limit a holistic or comprehensive approach that could be more lasting, that would be durable, and more sustainable.”

To that end, Fynn Bruey and her husband have started a non-profit called Tuki-Tumarankeh, which is a Wolof expression meaning, “It is the traveler who faces the most difficulty.” The non-profit is dedicated to advancing the welfare of displaced people through research, advocacy, and information, and publishes the world’s only academic journal devoted to raising the profile of displaced persons, the Journal of Internal Displacement (JID).

“That’s How Much It Is Part of My Core”

Throughout her remarkable life, Fynn Bruey’s stayed close to her roots—as a Liberian, a child of war, and a refugee from a very humble beginning. Drawing on her own experiences of trauma and abuse, Bruey is now committed to making sure that vulnerable people—women and children especially—can stay safe and protected, because, she says, “that’s what honestly keeps me grounded. And keeps me remembering that I can never forget where I came from, so that I can continue with that spirit of giving back to society, giving back to community, because a lot of people sacrificed for me to be where I am today.”

Fynn Bruey’s comprehensive education is a powerful tool she’s developed for fighting human trafficking. That, and her steadfast determination and indefatigable spirit to keep working, no matter what.

“Nothing anybody can do or say would deter me from continuing this journey,” Fynn Bruey says. “Because that’s how much it is part of my core.”

Back to Top

Welcome New Members

Please welcome our newest Global Washington members. Take a moment to familiarize yourself with their work and consider opportunities for support and collaboration!

Einstein Rising

Einstein Rising empowers Africa’s social entrepreneurs through its SME business development curriculum and provides access to startup capital. These wealth creators develop for-profit companies that tackle entrenched social and environmental issues without sacrificing the financial bottom line. einsteinrising.org

FIUTS

The Foundation for International Understanding Through Students (FIUTS) advances international understanding through cross-cultural experiences, student leadership, and community connections. Founded at the University of Washington in 1948, FIUTS programs connect international students, U.S. students, children and K-12 schools, and members of the community through programs that inspire dialogue and cultural exchange. fiuts.org

Gorman Consulting

Gorman Consulting is a firm that provides specialized measurement and evaluation services, primarily in the health sector. gormanconsulting.org

Back to Top

Member Events

July 12: West African Vocational Schools // Banquet

August 1: Upaya // 2019 Breakfast Briefing

Back to Top

Career Center

Program Coordinator, Amplio

Associate, Community Engagement, UNICEF USA

DV Services Program Manager II, YWCA of Seattle-King-Snohomish County

Check out the GlobalWA Job Board for the latest openings.

Back to Top

PRESS RELEASE: Bloodworks Northwest Names New President and CEO

Curt Bailey Begins as President & CEO at Bloodworks June, 2019

PRESS RELEASE

Curt Bailey, MBA, newly announced president & CEO of Bloodworks Northwest

Seattle, WA – Bloodworks Northwest’s Board of Trustees has announced the appointment of Curt Bailey, MBA, as Bloodwork’s president and CEO, succeeding James P. AuBuchon, MD who served in the position for 11 years. Curt Bailey, a leading expert in healthcare transformation, began his duties June 3, 2019, following Dr. AuBuchon’s retirement May 3, 2019.

“We are fortunate to have found such a capable individual to build on the legacy of Dr. AuBuchon’s extraordinary leadership in providing Bloodworks with a sound foundation to now pivot into an innovative future of improved blood health, providing the best care to everyone in our community and preserving the 75-year legacy of the organization,” said Craig Smith, MD, Chair, Bloodworks Board of Trustees. “I’m confident Bailey’s exceptional knowledge of the healthcare industry, business breadth and creativity will guide Bloodworks forward to a bold future in the evolving healthcare market.”

Continue Reading

How to Scale Global Conservation

@lldmtt via Twenty20

Partnerships are key to driving large-scale investment in the world’s natural capital

by Seth Olson, Analyst, Innovation

In 2014, Credit Suisse released a groundbreaking report that called attention to the 250-350 billion dollar funding gap in the conservation of natural resources. Several entrepreneurs, impact investors, and donor organizations reframed this gap as an opportunity. They began driving capital toward conservation and regenerative enterprises in their communities and across the globe.