By Urvashi Gandhi, Director – Global Advocacy, Breakthrough India

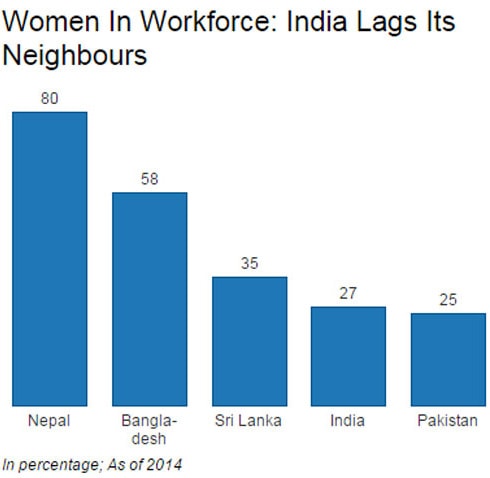

A very big question looming in front of us in India is why, despite the economic boom unleashed by economic reforms, women have been dropping out of the workforce in huge numbers? India has one of the lowest female labor force participation rates among the emerging market economies and developing nations. While slightly more women work in India than in Pakistan (27 per cent and 25 per cent, respectively), Pakistan’s female labor-force participation rate is on the rise — while India’s is deteriorating. The proportion of women working in Bangladesh is three times higher than that of India, which ranks last among BRICS countries.

Global data shows that no country in the world has achieved equality in unpaid care work or paid equality between men and women. When we are talking about the decreasing number of women’s participation in the formal workforce, there is also a need to talk about the role of men in creating a supportive environment that enables women’s participation in the formal workforce. This support by men and other members of the society is needed not just at the workplace, but also at homes and in communities. Currently the conversation is either totally missing or is being done in a very ad-hoc/reactive manner.

So, what kind of conversations do we need to have with men? There is a need to talk about men’s insecurities, which leads them to behave aggressively, many times using violence to control women. As a part of the socialization process, boys at a very young age are tutored to be competitive. They also told that “you are the best” or comparisons are made with girls in a very derogatory manner. So by the time they grow up, it is tough for men to accept women as their equal or in a position superior to them, whether at home or work.

Worldwide, there remains a widespread expectation that caring is women’s work, and men’s role as breadwinners should largely exempt them from any household chores or work that includes providing care. In a study by Promundo, “State of the World’s Fathers,” which drew on data from 23 countries across the world, significant proportions of both men and women agree that “changing diapers, giving baths to children, and feeding children should be the mother’s/woman’s responsibility.”

While we have worked with women to empower them, build their agency, encourage them to get educated and join the workforce, the shift really hasn’t happened with men. The norms of what roles men and women play still continue to haunt us, with men being the provider and women being the homemaker. Even though we do see women entering the formal workplace, they still continue to bear the burden of being the primary caretaker of the home and all family members, as men still continue to hesitate taking on roles and responsibilities in their own homes unless their wife is unwell. It seems that being irresponsible, clumsy, and disorganized at home is acceptable for men, while the same is frowned upon for women.

The report goes on to state that while many men are becoming more engaged as fathers and hands-on caregiving partners, in 23 middle- and high-income countries, the unpaid care gap between men and women has decreased by only seven minutes a day across a 15 year time span. Fewer than half of the world’s countries (48 percent) offer paid paternity leave on the birth of a child, and often this is less than three weeks – or sometimes only a few days. Even when paternity leave exists, too few fathers take leave after the birth or adoption of a child.

When this ‘duty’ of being the provider is taken away from men, they start to feel ‘insecure’. So if a wife earns more than her husband, if there is a female supervisor, or any woman who works outside her home – this is considered threatening to the identity of an “ideal man”. Thus, these spaces become the site for re-affirming the power and status for men and then to re-establish themselves as “better” than women. This re-affirmation and re-establishing often occurs through men resorting to being aggressive and using various forms of violence within and outside of homes.

The mindset which controls women at home for supremacy spills-over into public spaces and workspaces and is often also reflected in the way women are blamed for sexual harassment they face in public or in the work spaces. This mindset cements both the desire for control and the desire to remain in a position to assert that control. When it is threatened, it lashes out: when there are ‘too many’ women in a workplace, when women speak up in a workplace, when women make sexual harassment complaints etc. With the #MeToo Campaign gaining momentum, women increasingly are being blamed for reporting cases of workplace sexual harassment and have even faced backlash because of reporting. They experience snide, sexist and demeaning remarks about their character from co-workers, remarks that ‘she can’t take a joke,’ or that men have to be more fearful of women now, as they can use the law to ‘take revenge’. But in reality, if we see that even though in India we have had the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, the reporting is negligible. In some of the garment factories where my organization, Breakthrough, works around Delhi, our baseline data shows that only 1-2 cases of sexual harassment have been reported since the enforcement of the law, even with a workforce of 60-70% women.

The impact of this insecurity that is generally observed in the workspace is that we hardly see women in the top leadership positions of any major corporate house, as they face issues of a glass-ceiling. In 2017, women filled only a tenth of the most senior roles, according to a study done by Procurement Leaders. At the entry-level, the division of gender is more evenly distributed, as females account for 45% of employees. This paucity of women at the highest level undercuts the earning potential of the gender and pulls down average earnings as compared to men.

One more indicator of discrimination in the workplace is the existing gender pay-gap. According to a study by the World Economic Forum, India ranks at a disappointing 87 in the Global Gender Gap Rankings, which tracks data for 135 countries on the following criteria: Economic Participation and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health and Survival, and Political Empowerment. The World Economic Forum has also said that women may have to wait 217 years for the Gender Pay Gap to close globally.

If a woman is doing well, it might be said that “she has been manipulating her bosses to get favors and promotions.” How hard women have been working and their capabilities are rarely mentioned. Instead, promotions are mostly attributed to a woman’s looks. At the base of these behaviors lies men’s inherent fear of losing their position, privilege, power and entitlement, whereas when women gain agency, they gain their rights, and the power to make decisions and choices about their own lives.

But things need to change and are changing. We know that when any human being is in a more secure position and/or less competitive it is likely to change the dynamics. By changing the current socialization process of boys, we encourage them to accept diversity and inclusion as a norm and recognize that traits, skills, and qualities independent of gender identities exist in everyone. They can start to see that alternate ways are available to address conflict rather than violence or aggression, and begin building communication skills and most importantly a mindset of shared power and responsibility at homes and workspaces. As a result, they can begin recognizing and speaking-up against violence, including violence against women.

Additionally, we need to build more open, safe and non-judgmental spaces for dialogue between men and women, and among men, so that these issues of insecurities can be discussed and addressed, thus making them more secure about who they are, and realistic about what they can do and what is expected from others around them. This is how we can change the current narrative.

McKinsey’s latest report, Women in Workplace 2019, shows that – over the past five years, we have seen signs of progress in the representation of women in corporate America. Since 2015, the number of women in senior leadership has grown. This is particularly true in the C-suite, where the representation of women has increased from 17 percent to 21 percent. Many companies are promoting women into senior positions and aim to implement ‘women-friendly’ policies (such as flexible working hours). In workspaces, companies need to actively invest in training so that staff can be sensitized to the issues of the gender pay gap and understanding that our conditioning and biases influence it.

Companies are changing the way they want to retain women in their workforce and how they can be contributing. They are also increasing workforce participation by hiring more women and ensuring their retention by facilitating daycare, providing maternity and parental leave, flexible work hours, non-discriminatory practices, from hiring to firing, and establishing diverse gender inclusive work environments. Companies are also investing in training women in new skill sets, such as technology. Policies have been revised to assist women in joining the formal workforce after they have taken a break in their careers.

The current system socializes men towards a certain path: one of gender supremacy over gender parity, one where ‘ability’ is dictated by gender, where the only way to deal with anything that is not acceptable is violence. This system is not only destructive to others, it is destructive to those enacting it.

A system that encourages acceptance of diversity and inclusion and helps those who believe in masculinist ideologies understand that qualities exist independent of gender identities is a system that can be the first step in opening up lines of communication. It is a system that can share responsibilities and not have it concentrated at a few points.

The Vishaka Guidelines that informed the framing of the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act of 2013 helped companies across sectors to institutionalize internal complaints and train every employee on how to create a safer and inclusive work environment for everyone. Violence, whether in the home or public spaces, should be unacceptable, and perpetrators must not have any impunity. The need is to implement laws in their true spirit of justice and to uphold the values of equity and dignity of individuals at all levels, no matter what their background.

Breakthrough believes that there is a need for safer, gender diverse and inclusive workplaces to increase women’s participation in the formal workforce. There is also a need for a holistic approach of ensuring the identity and respect for working women within families, communities and in the formal sector.