March 2021 Newsletter

Welcome to the March 2021 issue of the Global Washington newsletter.

IN THIS ISSUE

- Letter from our Executive Director

- Issue Brief: Global Community Takes a Shot at COVID-19 Vaccine Equity

- Organization Profile: How Seattle’s Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Became a Global Leader in Testing COVID-19 Vaccines

- Goalmaker: New Head of PATH, Nikolaj Gilbert, Brings Flexibility and Partnership Prowess to Global Health

- From Our Blog: Vaccines Touch Down Across Africa: Now the Work Begins

- Action Alert: Aid Organizations Respond to Instability and Violence in Myanmar

- Action Alert: Millions at Risk from Evolving Crisis in Northern Ethiopia’s Tigray Region

- Welcome New Members

- GlobalWA Member Events

- Career Center

- GlobalWA Events

Letter from our Executive Director

Just over two weeks ago, the first COVID-19 vaccines were received in Ghana, marking the start of a rollout in low- and middle-income countries. While this is incredibly hopeful, there is still worry that the vaccine will not have an equitable distribution globally. And, that the pandemic will continue for years to come if we do not mobilize for a quick worldwide vaccination campaign.

Below is our issue brief, which provides a good overview of this topic and discusses how Global Washington members are working to ensure equitable access to COVID-19 prevention and treatment options in low- and middle-income countries. Also, stay tuned for in-depth member stories on this issue later in the month, as well a virtual event on March 24 with speakers from VillageReach, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Medical Teams International, and the International Rescue Committee.

In addition to vaccine equity, we have also posted two Action Alerts on situations that are unfolding in Ethiopia and Myanmar, to which many of our members are responding. Both stem from underlying political crises that are driving widespread suffering and human rights violations.

Lastly, I am excited to share a report we published on our 2020 Goalmakers initiative, including key insights and cross-cutting themes that emerged from the series of events that we held last year on the Sustainable Development Goals. These are themes we will continue to build on this year and in the years ahead.

Kristen Dailey

Executive Director

Issue Brief

Global Community Takes a Shot at COVID-19 Vaccine Equity

By Joanne Lu

A nurse vaccinates a baby at a clinic in Accra, Ghana. Photo by Kate Holt, MCSP. Flickr. (CC BY-NC 2.0).

On February 24, Ghana became the first country outside India to receive COVID-19 vaccine doses as part of a global initiative, called COVAX, to provide equitable access to the vaccines, particularly in low-income countries.

“This is a historic step towards our goal to ensure equitable distribution of COVID-19 vaccines globally, in what will be the largest vaccine procurement and supply operation in history,” the World Health Organization (WHO) said in a press release.

Since then, more than 16 million COVID-19 vaccine doses have been shipped to 27 countries through the COVAX initiative, according to a March 18 update from the WHO. In Africa, 25 million vaccines have been sent to 38 countries through COVAX, bilateral deals and donations, and 30 of those countries have started vaccination campaigns.

While these developments are certainly cause for celebration, they come as some of the world’s richest countries have purchased a surplus of more than 1.2 billion excess doses, according to The ONE Campaign. Canada, for example, has secured enough vaccines to immunize its population five times over. For comparison, nearly 7 million doses have now been administered in Africa, while the U.S. surpassed that number in just four days.

Meanwhile, the majority of low- and middle-income countries have had to “watch and wait,” WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus wrote in the Guardian. In mid-February, the UN reported that 2.5 billion people in 130 countries still had not received a single vaccine dose.

Even Ghana – which opted to administer its 600,000 AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccines to 600,000 people as their first dose, instead of to 300,000 people as their two recommended doses – still has to trust that its government or COVAX will come through in time with enough vaccines to give people their second doses. With Ghana’s government planning to vaccinate 20 million people by the end of October (meaning 40 million doses), the shipment on February 24, though “historic,” was still a just small step that should have happened much, much sooner.

The rush by wealthy countries to secure first access to vaccines has been dubbed “vaccine nationalism,” which the WHO and others have condemned.

“Even as they speak the language of equitable access, some countries and companies continue to prioritize bilateral deals, going around COVAX, driving up prices and attempting to jump to the front of the queue,” Dr. Tedros said in January. “This is wrong.”

Additionally, experts warn that vaccine nationalism will slow recovery – both from the virus and its economic effects.

“[Vaccine nationalism] is a problem morally. It’s a problem in terms of public health, because we need to vaccinate more widely in order to tackle issues like the barriers. And it’s bad news in terms of the economic impact as well,” Mark Suzman, CEO of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, said in February.

The Gates Foundation helped set up the COVAX Facility and has also funded vaccine, therapeutics and diagnostics research and development. Suzman says that some of the modeling supported by the Gates Foundation shows that there’s going to be “much longer, lingering economic damage” if vaccinations are concentrated in wealthy countries and not distributed evenly.

According to the World Economic Forum, high-income countries and regions, including the U.S., the U.K., and the European Union, could lose around $119 billion per year, until a global recovery is secured.

“A me-first approach might serve short-term political interests, but it is self-defeating and will lead to a protracted recovery, with trade and travel continuing to suffer,” wrote Dr. Tedros in the Guardian. “The threat is clear: As long as the virus is spreading anywhere, it has more opportunities to mutate and potentially undermine the efficacy of vaccines everywhere. We could end up back at square one.”

According to the WHO, there’s a lot that countries and companies can do to promote equitable vaccine access, including dose sharing, technology transfer, voluntary licensing, and waiving intellectual property rights. Oxfam has called for a “People’s Vaccine,” one that is “mass-produced, fairly distributed, and made available to every individual, rich and poor alike.” A People’s Vaccine, the organization says, would “unlock the production of billions more doses in the shortest amount of time and ensure access for everyone, everywhere across the globe.”

Meanwhile, the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center has stepped up to serve as the coordinating center for vaccine clinical trials of the COVID-19 Prevention Network (CoVPN) to continue developing vaccines, even though there are a few options on the market already.

“We need multiple successful vaccines to protect the entire global population from COVID-19,” said Dr. Larry Corey, former president and director of Fred Hutch, who will co-lead the CoVPN’s vaccine testing pipeline.

While vaccine development and manufacturing continues to ramp up, organizations like Americares are also working hard to support “vaccine readiness.” Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, says that a country’s vaccine readiness can be assessed on four fronts: awareness of evidence-based information; acceptance of the new vaccine; accessibility to the vaccine, especially in the hardest to reach places; and availability of infrastructure to store and deliver vaccines. In particular, Americares is tackling misinformation head-on, with weekly Q&A videos about COVID-19 vaccines and other resources.

Mercy Corps’ CEO Tjada D’Oyen McKenna says that important lessons about building public trust can be drawn from past Ebola outbreaks. In Liberia, for example, Mercy Corps helped train more than 15,000 community messengers to help combat misinformation in their own communities, reaching more than 2.4 million people. (That’s over 56 percent of the population.)

Mercy Corps is especially concerned about the vaccine reaching people in conflict zones, where the pandemic tends to take a back seat to other basic needs that feel more pressing, suspicion and misinformation thrive, and violence has destroyed infrastructure for vaccine delivery and threatens the safety of health workers. In late February, the U.N. Security Council passed a resolution demanding “vaccine ceasefires” in conflict zones.

Similarly, organizations like Medical Teams International are advocating for migrants and refugees to be included in vaccination campaigns in countries like Colombia. Closer to home, Medical Teams International is getting together equipment, like freezers, to distribute vaccines in Washington state.

Of course, effectively executing the largest global vaccine rollout in history requires working closely with local leaders. CARE’s comprehensive two-year vaccine initiative will support national, regional, and local governments with logistics, public education and strategies to ensure fast and fair vaccine distribution.

VillageReach also participates daily in Ministry of Health-led response efforts, including vaccine planning. Recently, Mozambique received its first shipment of vaccines. VillageReach will support the Mozambique Ministry of Health with the supply chain planning and logistics, as well as training vaccinators. With its organizational mission of reaching the last mile, VillageReach knows all too well the importance of working with community health workers, like vaccinators, to reach even the most remote places.

PATH – which supports the Serum Institute of India, manufacturers of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines that are being shipped through the COVAX Facility – also recognizes the critical role of vaccinators. That’s why even before the COVID-19 pandemic, PATH’s Living Labs Initiative was working with frontline health workers to understand the day-to-day challenges that prevented them from achieving their immunization targets and professional goals. Now, insights from these health workers are helping to optimize labeling for COVID-19 vaccines, informing local adaptations to WHO’s training guidance for health workers, and supporting the ministries of health in Kenya and Zambia as they develop vaccine plans.

“We know from experience that when we listen to health workers, they identify challenges—and solutions—that no one else sees,” says Dr. Joseph Kayaya, lead product manager with PATH’s Living Labs Initiative.

In Africa, the experience and expertise of health workers is on full display right now as vaccination campaigns there have covered a lot of ground quickly – despite receiving late shipments of limited doses.

“This is due to the continent’s vast experience in mass vaccination campaigns and the determination of its leaders and people to effectively curb COVID-19.” said WHO Regional Director for Africa Dr. Matshidiso Moeti in a press release. “Compared with countries in other regions that accessed vaccines much earlier, the initial rollout phase in some African countries has reached a far higher number of people.”

Although the vaccine rollout so far has been slow and uneven, the fact that it’s happening is an encouraging sign that recovery is on the horizon. Tracking the pandemic from its beginning was the data-visualization company Tableau. Now, it’s turned its attention to tracking global progress toward recovery, helping to inform individual behavior, business decisions, and government policy. The company’s new Global Tracker pulls information daily from multiple sources to allow people to see and interact with data on things like localized disease spread, testing and vaccination, and social policy indicators, both in the U.S and globally.

Through private and public sector cooperation, a massive global vaccination campaign that reaches every person is possible. But it will require setting aside the business-as-usual notion of vaccine nationalism in order to put all of us first. As Dr. Tedros said: “While the virus has taken advantage of our interconnectedness, we can also turn the tables by using it to spread life-saving vaccines further and faster than ever before.”

The following GlobalWA members are working toward global equity on COVID-19 treatment and prevention.

Americares

As COVID-19 infected millions around the world and forced families into isolation, Americares launched into action, responding in more than 30 countries with critically needed protective gear and training for frontline health workers. Since launching its response last February, the health-focused relief and development organization has dedicated every resource to ensure health workers stay safe and can continue their lifesaving work. Americares response also included telehealth consultations to ensure patients continued to receive care during community lockdowns and medical facility closures, launched public education campaigns to combat misinformation and made water system improvements to help slow the spread of the virus. The “Americares COVID-19 2020 Special Report” details its global response to the crisis.

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

In their 2020 Goalkeepers report, Bill and Melinda Gates reflected on how COVID-19 has impeded progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals, and what the world needs to do to come together to end the pandemic. For one thing, the foundation believes a shared global response is critical: “Together, we can ensure a safe and effective vaccine is distributed equitably and affordably for every last person on earth—not just those with ability to pay. The virus does not adhere to borders, and neither can the vaccine. A global response must also aim to build more resilient health systems that protect the world’s most vulnerable and prevent future disease outbreaks.” To date, the foundation has committed about $1.75 billion to support the global response to COVID-19, including funding the development and procurement of new tests, treatments, and vaccines, and supporting interventions to alleviate the social and economic effects of the pandemic globally. The focus for 2021 is to ensure equitable, timely, and scaled delivery of proven interventions.

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

Fred Hutch is part of the global scientific community racing to stop the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientists from across the organization have been tackling all aspects of the disease and the virus that causes it – including researching how it spreads, how it affects people’s bodies, and developing potential therapies and vaccines. In July 2020, Fred Hutch became the coordinating center for vaccine clinical trials of the COVID-19 Prevention Network, leading operations across at least five large-scale efficacy trials with over 100 clinical trial sites in the U.S. and abroad. Three months later Fred Hutch opened the COVID-19 Clinical Research Center, one of the first stand-alone facilities in the nation designed to test novel interventions to treat and prevent COVID-19, from Phase 1 through 3 clinical trials for COVID-19-positive participants and, in the future, participants with other infectious diseases.

Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) builds on decades of research and advocacy to shed light on the immediate and long-term impacts of Covid-19 on human rights. The pandemic has exposed the frailties in our social system. While billionaires grew richer by $1.9 trillion in 2020, hundreds of millions of job losses were concentrated in low-wage industries. These losses disproportionately affected women and people of color, pushing many into poverty. HRW reported on the devastating impacts of Covid-19 on historically marginalized communities and the most vulnerable members of our population in the U.S. HRW also called on the U.S. Congress to safeguard frontline meatpacking workers and spoke out on the inaccessibility of online vaccine registration systems for the elderly. The organization has also continued to sound the alarm on rising domestic violence rates, and advocated for protecting tenants’ rights to adequate housing and financial relief. In 2021, HRW remains steadfast in its commitment to build a rights-respecting future and defend human rights for all.

International Rescue Committee

Over the past year, the IRC scaled up its response to the coronavirus pandemic in over 40 countries, providing essential health care services to refugees, sharing vital information about hygiene, handwashing, and self-isolation, training health workers on how to keep themselves safe, and providing protective equipment to aid workers. Through partnerships with organizations like COVAX, the IRC is helping countries prepare for the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines. The IRC is also working with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance to advocate for equitable access to vaccines—including for populations affected by crisis. As vaccines become available, the IRC will help administer them through the network of health facilities it supports around the world. The IRC also helps refugee and immigrant communities impacted by COVID-19 in the United States, including in Washington state, through health services, remote learning support for K-12 students, distribution of food and masks, emergency financial assistance, and more.

Lynden

Lynden International is a global freight logistics provider, headquartered in Washington state, with developed services to multiply the capacity of organizations doing global health and humanitarian work. Before the coronavirus pandemic, Lynden participated in epidemic response measures for Ebola and Zika outbreaks and continued to work to build health system resilience with government, foundation, and NGO stakeholder clients worldwide. To combat the spread of COVID-19 Lynden has worked with these same organizations to deploy personal protective equipment (PPE), sanitizing supplies, and test kits globally to lower- and middle-income countries, as well as native communities and remote locations in the United States since March 2020. While COVID-19 vaccines were in development, Lynden worked with logistics partners to enhance cold chain capabilities in Africa, and it began vaccine distribution to underserved communities in Alaska and offshore locations in the U.S. Lynden is also expediting deployment of cold chain containers in which vaccines are transported and collaborating with organizations supporting the UN COVAX facility and African Union efforts to distribute vaccines equitably.

Medical Teams International

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, Medical Teams International President & CEO Martha Newsome has placed a high priority on global equity in treatment and prevention. For example, when the first cases were identified in the world’s largest refugee camp in Kutupalong, Bangladesh, in May 2020, Medical Teams responded by opening the camp’s first isolation and treatment center in partnership with Food for the Hungry and UNHCR. Medical Teams’ strategy of educating and equipping community health workers has empowered them to share best practices in prevention throughout impacted communities in Uganda, Guatemala, Colombia, Lebanon, and Bangladesh. In the Pacific Northwest over the past year, Medical Teams’ staff and skilled volunteers have tested nearly 30,000 people. Globally, Medical Teams has conducted more than 1.91 million screenings. These numbers represent vulnerable populations without access to traditional healthcare, such as refugees, migrant farm workers, and individuals and families lacking housing.

Mercy Corps

As higher-income countries continue to secure agreements for COVID-19 vaccines above and beyond what’s needed for their populations, millions of people are standing at the back of the line. Mercy Corps is advocating for equitable vaccine access for lower-income and conflict-affected countries unlikely to have widespread access to vaccines before 2023, as well as often overlooked and hard-to-reach populations, like refugees and internally displaced people, who are at risk of being left out of vaccination efforts. In Colombia, Mercy Corps is partnering with El Espectador, a national Colombian newspaper, on a nationwide campaign to build empathy, understanding and support for Venezuelans in Colombia, and to advocate for vaccine equity for migrants. Mercy Corps is also working to combat misinformation and build vaccine acceptance through information campaigns launched during COVID.

OutRight Action International

In the wake of COVID-19, OutRight Action International launched a research project to document the immediate and severe impact of the pandemic on LGBTIQ people globally. Its findings were based on interviews with advocates in 38 countries, and featured on BBC Newshour among other news outlets. OutRight also launched a Global LGBTIQ Emergency Fund to support grassroots LGBTIQ organizations on the frontlines of providing emergency assistance to LGBTIQ people experiencing loss of income and food, lack of access to HIV medication and healthcare, increased domestic violence, and even scapegoating by religious and government leaders. Moreover, LGBTIQ people often are not reached or left behind by government or traditional relief efforts, and many grassroots LGBTIQ organizations are on the brink of survival – threatening to set the movement for equality and human rights back by years. To date, OutRight’s Emergency Fund has raised more than $1.65 million from 300+ companies, foundations and individuals and has issued 125 grants in 65 countries, reaching more than 50,000 people. OutRight will be issuing a second call for applications and additional grants this spring and throughout 2021, as funding is available.

Oxfam America

Oxfam America is advocating for a People’s Vaccine, a COVID-19 vaccine that is patent-free, mass-produced, fairly distributed, and made available free of charge to every individual across the globe. Within this work, Oxfam America is leading a coalition of partners to pressure the Biden Administration to ensure the technology and know-how to make COVID-19 vaccines is shared with the world. This coalition wrote a public letter calling on President Biden to champion a People’s Vaccine, which was signed by more than 200 leaders from the fields of public health, medicine, global development, and racial justice, as well as faith leaders, economists, Nobel laureates, former members of Congress, and artists. Oxfam America is leading other efforts, taking both public and insider approaches, to pressure the Biden Administration to push for a People’s Vaccine, which have included meetings with Administration officials and a grassroots petition to President Biden. Watch Oxfam America’s video about the People’s Vaccine here.

PATH

PATH has been closely involved with the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator, a global public-private-philanthropic collaboration to accelerate the development, production, and equitable rollout of COVID-19 tests, treatments, and vaccines. COVAX is the vaccines pillar of the ACT Accelerator and PATH has been mobilizing its staff, networks, and partnerships to anticipate and address specific country needs. Through PATH’s expertise in vaccine financing, procurement, and partnerships, it is assisting the COVAX Facility with program design and operationalization. PATH is also leveraging its manufacturing expertise to evaluate production capacity and offering strategies for scale-up. In addition, PATH has been providing technical assistance to support COVID-19 vaccine trial-site readiness in Africa and Asia.

Save the Children

Save the Children responded to COVID-19 across 87 countries, including the United States, reaching 29.5 million coronavirus-affected people. Its teams launched and sustained an emergency response to contain the spread, protect communities, and support children and families. As vaccines are developed and rolled out, Save the Children is pressing leaders around the world and working with its partners to ensure the most vulnerable people will have access and are prioritized, as well as health workers, community leaders and teachers, who are critical to keeping children safe and learning. Find out more in a recently published report: A Chance to Get it Right: Achieving equity in COVID-19 vaccine access. Save the Children has been adapting and expanding how it delivers world-class programs and advocates for children, as well as launching new and innovative initiatives to prevent, mitigate and respond to the pandemic’s devastating impacts. More information on Save the Children’s overall response and impact can be found in its COVID-19: One Year On Global Impact Report.

Splash

Splash is a non-profit organization that delivers child-focused water, sanitation, hygiene (WASH), and menstrual health solutions in some of the world’s largest, low-resource cities. Its vision is for children in urban poverty to thrive and reach their full potential. Through Project WISE (WASH in Schools for Everyone), Splash plans to reach 100% of government schools in two major growth cities: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Kolkata, India by 2023, serving one million kids. As schools re-open globally, Splash is especially focused on increasing handwashing with soap, the first line of defense against COVID-19. It does this through behavior change programs for teachers and students, as well as through patented handwashing stations designed just for kids. Through Splash Social Enterprises, the organization has launched a new project to design handwashing stations for a broader array of institutions (such as health care facilities and rural schools), helping provide access to handwashing for people of all ages in low- and middle-income markets.

Tableau Foundation

Software company Tableau’s free, publicly-accessible COVID-19 Data Resource Hub includes real-time data on case reports from Johns Hopkins University, the WHO and the CDC, as well as a curated gallery of visualizations from national news and health organizations. The foundation has also ramped up its Community Grants Program, expanding the number of grantees and streamlining the application guidelines. Tableau has created two other giving campaigns for employees: one to support frontline health workers, and another, the COVID-19 Response Fund, to meet the needs of community organizations and non-profits serving at-risk communities that are disproportionately impacted by the disease and its repercussions.

VillageReach

In the early months of the pandemic, VillageReach joined like-minded collaborators to form the COVID-19 Action Fund for Africa, a group of 30 organizations focused on getting personal protective equipment (PPE) to community health workers in Africa. Many African countries were shut out of the PPE market, making frontline health workers and their patients extremely vulnerable. More than 57 million pieces of PPE have been secured for 18 countries since August 2020. Fast forward to today and 80 days have passed since the first health worker in Washington state was vaccinated. COVID-19 vaccines arrived recently in Africa, but the number of available doses does not match the need. And as U.S. leaders announce vaccine availability for every adult by May, VillageReach continues to advocate for health workers in Africa – they need vaccines NOW.

World Vision

World Vision is responding to the devastating impact of COVID-19 in more than 70 countries. The organization is using its global reach and grassroots connections to encourage vaccine acceptance and uptake. This means ensuring that communities are accurately informed of the nature and purpose of each COVID-19 vaccine, that leaders and champions are equipped to support their constituencies, that public health decision makers understand vaccine acceptance barriers and the science of reducing vaccine hesitancy. World Vision is using mobile phones to enable health workers, in even the most remote areas, to access vital voice message trainings on COVID-19. Its networks to combat the spread and impact of COVID-19 include 300K faith leaders, 181K community health workers, government and private sector partners, as well as World Vision’s own humanitarian and development experts. Globally, World Vision participates in COVAX1 in an advisory role, providing guidance on community engagement and participating in a working group on demand-side preparedness.

Organization Profile

How Seattle’s Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Became a Global Leader in Testing COVID-19 Vaccines

By Joanne Lu

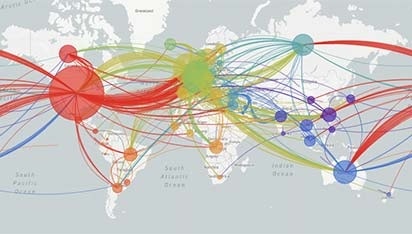

The global path of COVID-19. Image courtesy of Fred Hutch.

When COVID-19 first made landfall in the U.S. last year, it made its grand entrance in Snohomish County, Washington, and eventually turned Seattle into the country’s “coronavirus capital” for some months. So, in a way, it’s only fitting that the institution at the center of the vaccine development campaign to end the pandemic is based in Seattle, as well.

On the face of it, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center may sound like an unlikely candidate to coordinate COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials. But “Fred Hutch” or “the Hutch” as it’s known, was actually an obvious choice, after having worked for more than 20 years on a vaccine to end another pandemic: HIV/AIDS.

Fred Hutch was founded in 1975 as a center dedicated to studying cancer – and that work continues. But it soon became renowned for its work on other diseases, too, especially HIV (which also causes a type of cancer called Kaposi sarcoma).

Fred Hutch in Seattle. Photo courtesy of Fred Hutch.

It was through HIV research that the center’s former president and director, Dr. Larry Corey, became friends and colleagues with Dr. Anthony Fauci in the 1980s. In fact, it was Fauci who encouraged Corey in 1998 to co-found what became the HIV Vaccine Trials Network (HVTN), the world’s largest publicly funded international collaboration conducting clinical trials of HIV vaccines. The HVTN is headquartered at Fred Hutch and supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), which is headed by Fauci.

So, when COVID-19 hit, it was no surprise that Fauci tapped Corey, along with the global network and expertise of Fred Hutch and the HVTN, to coordinate vaccine trials through a newly-formed clinical trials network: the COVID-19 Prevention Network (CoVPN). The plan was to “harmonize” trials of various vaccines so they could be compared to each other by asking a common set of questions, setting a common set of goals, and measuring success with a common set of tests, carried out by independent laboratories. And it needed to be done as quickly as possible.

CoVPN manages more than 100 clinical trial sites in the U.S. and around the world, including in Mexico, Peru, Brazil, Argentina, South Africa, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi. So far it has tested, and is still evaluating, vaccines from Moderna, AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, Novavax, and Sanofi.

“Our large network, which is very connected across different disciplines, was a really obvious choice to move forward these COVID-19 vaccines,” says Dr. Michele Andrasik, a senior staff scientist in the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division of Fred Hutch and director of Social & Behavioral Sciences and Community Engagement at HVTN and CoVPN.

Dr. Michele Andrasik, a senior staff scientist in the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division of Fred Hutch and director of Social & Behavioral Sciences and Community Engagement at HVTN and CoVPN. Photo courtesy of Fred Hutch

The HVTN’s three core areas — operations/leadership, statistical, and laboratory — are all housed at Fred Hutch. Additionally, with clinical trial sites spread across the country and around the world, the Hutch had all the mechanisms and processes in place to ensure that COVID-19 vaccines could get through trials safely, effectively, and relatively quickly.

“We’ve been incredibly successful at shepherding through HIV vaccine trials, so for us, it was a seamless shift,” says Andrasik of taking on the responsibilities of the CoVPN.

“It’s always been our opinion that vaccines are what is going to get us out of this,” says Andrasik, but testing and developing vaccines that work is only the first step. Vaccinating people – enough people – is the goal.

Doing so requires building people’s confidence in vaccines. So, Fred Hutch did what it has always done. Its external relations team reached out to community partners in Washington and around the world – in Asia, in the Pacific Islands, in Indigenous communities, in the Latin American diaspora, in the Black diaspora – to learn how the disease was impacting their communities. They asked leaders what their communities needed to know about the vaccines and what was needed to not only enroll people in vaccine trials, but to increase the number of people getting vaccinated.

According to Dr. Stephaun Wallace, a Fred Hutch staff scientist and HVTN and CoVPN’s director of external relations, skepticism about the trial process or of the vaccines usually falls into four main categories: questions about the benefits, safety and side effects; concerns about the speed with which the vaccines have been developed and whether they work on people “like me;” distrust in the political and economic motivations of the governments and companies involved; and belief in misinformation or conspiracy theories.

Dr. Stephaun Wallace, a Fred Hutch staff scientist and HVTN and CoVPN’s director of external relations. Photo courtesy of Fred Hutch.

Fred Hutch is working especially hard to ensure representation of Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) communities in vaccine trials, because diversity is important for finding a vaccine that works in all kinds of people, and it is necessary for building vaccine confidence. People are more likely to take a vaccine that they know worked on someone who looks like them, says Andrasik.

Again, community engagement is key to increasing BIPOC representation in trials. Fred Hutch’s clinical trial sites have always been in the communities where they work, says Andrasik, and the people who work at those sites are members of the community themselves. Wallace says the team works hard to acknowledge community concerns, provide accurate information, and ensure the ethical conduct of research.

Vaccine confidence isn’t as great of an issue outside of North America and Western Europe, says Andrasik. Instead, the challenge in many low- and middle-income countries is just getting the vaccines there. Besides an inequitable global supply of vaccines, inconsistent pricing is also part of the problem, as well as inadequate public health infrastructure that limits the types of vaccines that are viable in areas without sufficient cold storage capacity, according to Raquel Sanchez, the managing director of Global Oncology at Fred Hutch.

Raquel Sanchez, the managing director of Global Oncology at Fred Hutch. Photo by Robert Hood / Fred Hutch News Service.

Andrasik says Fred Hutch’s approach is to let global partners take the lead. “They’ll let you know what they need in terms of support,” she says, but ensuring that the trials go through as quickly as possible – without bypassing any safety procedures – is one way they’re helping low- and middle-income countries get vaccines sooner.

As vaccines are now being rolled out, community engagement is still key. According to Andrasik, some of the most successful places in the country that are distributing vaccines are doing so in collaboration with faith-based organizations, community organizations, and long-standing institutions that have earned the trust of the communities they’re in. Locally, Fred Hutch is working with the Washington Department of Health and Seattle and King County Public Health to further that effort.

But it’s always a learning process. For example, early on, Seattle – and other cities – thought that mass vaccination sites in BIPOC communities were the answer to administering vaccines equitably. Instead, it quickly became clear that the people who were accessing the sites were not the people who lived in those communities. Instead, it was mostly people who had the ability to chase down appointments, as they worked from home on their computers, who then drove into BIPOC communities to get their vaccinations.

In response, Andrasik says there has been a “massive effort” by the city, local, and state government to deploy pop-up and mobile sites that go directly into BIPOC communities. In some situations, unique URLs have been created for community-based organizations to give to their clients in order to ensure that vaccination appointments are actually being filled by BIPOC individuals.

Although there’s still a lot of work to do to ensure equity as we move closer to ending this pandemic, Andrasik is optimistic: “This is by far the greatest and most concerted effort toward equity that I’ve ever seen in my life, and it’s really amazing to be a part of it.”

Goalmaker

New Head of PATH, Nikolaj Gilbert, Brings Flexibility and Partnership Prowess to Global Health

By Andie Long

Photo courtesy of PATH.

Nikolaj Gilbert joined PATH, a global public health organization headquartered in Seattle, in January of 2020 – just as the first cases of COVID-19 began appearing globally and shortly before the first U.S. cases were reported in Washington state. With little more than a year on the job, having immigrated to the United States from Denmark with his family and onboarded to PATH almost entirely virtually, the new CEO already has a strong vision for the future, one that challenges it to be an even better global partner.

PATH works locally, with national and sub-national health organizations around the world, as well as globally with partners like the World Health Organization, developing vaccines, devices, and tools that can reach people who would otherwise not have access. This expertise has been essential in light of the global pandemic, as many of the hardest hit communities navigate COVID-19 on top of other major health threats. Doing this well requires a strong set of institutional values that drive all of PATH’s work – and Gilbert is the right leader for the job.

In early June when a renewed push for racial justice in the U.S. reached a fever pitch, Gilbert said that PATH accelerated its efforts to ensure the organization held its staff and leaders accountable to its values and for the first time, publicly acknowledged racism as a public health issue. In a statement, PATH said that “…while racism has a uniquely devastating role in the history of the United States, it is a global crisis, marginalizing people and communities everywhere.”

Gilbert has been a staunch advocate for vaccine equity and a multilateral approach to pandemic response. In an article for Devex in October, he called out nationalist policies that have undermined global strategy and fractured the cooperation needed to end the COVID-19 pandemic, warning, “No country will reap the full benefits of a COVID-19 vaccine by only considering the needs of its own population.” More recently, he has used his voice to draw attention to the financing and market challenges of delivering medical oxygen to health care facilities in low- and middle-income countries.

Throughout the pandemic, PATH has worked closely with Gavi/COVAX, the vaccine arm of a global public-private-philanthropic collaboration that was formed to stop the disease in its tracks. And throughout Africa and much of Southeast Asia, PATH has been coordinating with countries to refine their plans for an equitable rollout that prioritizes those who are most vulnerable.

REDEFINING WORK / LIFE BALANCE

Gilbert’s values transcend PATH’s offices. With remote work widespread during the pandemic, many of us have become accustomed to seeing our colleagues occasionally interrupted by their children, pets or even their partners during video calls. This real life incursion has served to remind us of our shared humanity.

Gilbert’s daughters range in age from six to 13. The girls are not yet fluent in English, so the move has been particularly challenging for them, he says, especially as Seattle schools shifted to all-remote learning.

What we all need to remember, he says, is “It’s okay to have your kids jumping on your lap in a meeting.” They’re as much a part of your life as your work is.

Just then, Gilbert’s six-year-old can be heard in the background yelling “Daddy!” He hesitates a split second before saying, “I need to tell her I’m in a call, and I’ll be back.”

After the short interlude, Gilbert is back on camera, his wry smile acknowledging the perfect illustration of what we were just discussing.

In terms of balancing work and home life, Gilbert insists there are ways organizations like his can support employees who have children, without people having to compromise their careers. For him, it’s about demonstrating flexibility in how you evaluate people on their contributions to the organization.

“It’s not always about being physically somewhere for a number of hours,” he says. “It’s what you bring.”

COLLECTIVE LEADERSHIP

Gilbert brings to PATH a strong belief in what he calls collective leadership. “I’m not very hierarchical,” he says. “I seek advice from people who have the knowledge, regardless of where they sit in the organization.”

Reflecting this vision, PATH has recently undergone a reshuffling in its organizational structure, having named four new executives representing PATH’s country teams and “reduced the layers” between top executive levels and the rest of the organization. This new model intentionally addresses the dynamics between PATH’s U.S.-based headquarters and its country-based programs, making sure the country teams have “the power and influence to do what is best and make those decisions.”

The new five-year organizational strategy PATH will be launching this summer focuses on strengthening health systems globally, as well as moving toward a more country-driven model.

Gilbert says he is glad he didn’t have a strategy already in place coming into PATH “because what’s happened in the last year has changed everything.”

The process of setting a new strategy at PATH took nine months, and encompassed organizational-wide surveys together with partners, donor, and staff interviews. “It has been a challenge,” he admits, “but it has also been extremely rewarding and brought us together as an organization.”

PARTNERSHIPS DONE RIGHT

While most organizations find partnerships difficult to build and even more challenging to maintain, PATH’s whole mission depends on navigating public-private partnerships to improve global health. Whether it’s finding the right partners to advance a health innovation, or launch a product, or build the capacity of local manufacturers, Gilbert says, “This organization is pretty darned good at partnerships.”

Having previously served as director of partnerships at the United Nations Office of Project Services, Gilbert brings a wealth of insight on what it takes to manage complex partnerships successfully. One key he says is to forge “fewer partnerships, but more quality partnerships.”

All parties need to be honest and transparent, he says, about what they expect, as well as how the partnership will advance the “greater good” and the needs of both organizations. “There’s no doubt in my mind that partnerships are the way forward,” Gilbert says.

And what better place to be building partnerships than in Washington state?

“It’s amazing to be in an environment where there’s so much focus on critical issues and global health,” Gilbert says. “There are so many like-minded partners and stakeholders here, like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and many corporate and philanthropic donors, that want to help.”

“The mentality for partnerships here … I feel that when people talk about entering partnerships, it’s really something that they see the benefit of. Maybe here there is this history and legacy of how these partnerships have transformed and led to many innovations in different areas.”

While Gilbert knew Washington state was home to many important global health organizations, he says he didn’t realize until he moved here the “amazing energy” of those local stakeholders and how well they connect and work together to scale up solutions. “That’s quite remarkable and the innovation capacity and passion in this part of the world has surprised me and stunned me to be honest.”

From Our Blog

Vaccines Touch Down Across Africa: Now the Work Begins

By Emily Bancroft, President, VillageReach

I never thought I’d be so excited by pictures of boxes being unloaded from airplanes. When I saw the photos come streaming across social media this week, I breathed a deep sigh of relief. The pallets being wheeled onto the tarmac meant that COVID-19 vaccines had arrived in Mozambique, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Côte d’Ivoire, Malawi and many other African countries. As government officials and partners began to unpack the containers, we all knew the hard work was just beginning.

Malawi officials receive COVAX delivery at Kamuza International Airport. | Photo Credit: Hope Ngwira

Over the last year, as the scientific community quickly mobilized to develop, test and produce multiple effective vaccines, the focus for VillageReach has been protecting health workers and communities against the virus. As an organization dedicated to the delivery of vaccines, medicines, supplies and information, COVID-19 vaccine delivery has been constantly on our minds. We participated in the Country Readiness and Delivery working group of the vaccine pillar of the Access to COVID Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) to help link global-level plans with country efforts. Read more.

Action Alert

Aid Organizations Respond to Instability and Violence in Myanmar

Feb 9, 2021 – Teachers protesting a military coup in Myanmar. Credit: Ninjastrikers. Licensed CC BY-SA 4.0.

The fragile democracy of Myanmar, which held for a decade, was upended at the beginning of February 2021 when the military staged a coup to prevent newly elected members of parliament from being confirmed. The military’s favored party lost the November elections in a landslide to the National League for Democracy, the governing party of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

In response to the coup, millions of Myanmar’s citizens and residents took to the streets to protest, many banging on pots and pans to “drive the ‘military regime’ out of the country.” The demonstrations soon evolved into a nationwide strike of civil service workers, with nurses and doctors the first to refuse to work. They were followed quickly by teachers, as well as bank tellers and other private sector employees. All this after a grueling year of lockdowns in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, today the country has nearly ground to a halt. Read more.

Action Alert

Millions at Risk from Evolving Crisis in Northern Ethiopia’s Tigray Region

(UPDATED March 4, 2021)

Credit: Joost Bastmeijer for Medical Teams International.

According to the latest report from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), at least 4.5 million people in the Tigray region of Ethiopia are in dire need of assistance, with those in rural areas the hardest to reach. Food is scarce and the lack of water, sanitation, and hygiene services has increased the risk of deadly disease outbreaks. What’s more, people in the region have few functional health facilities to turn to. Read more.

Welcome New Members

Please welcome our newest Global Washington members. Take a moment to familiarize yourself with their work and consider opportunities for support and collaboration!

Nia Tero

Indigenous peoples sustain many of the healthiest ecosystems on Earth: areas rich in biodiversity and systems essential to our global climate, fresh water, and food security. Nia Tero exists to ensure that Indigenous peoples have the economic power and cultural independence to steward, support, and protect their livelihoods and territories they call home. These places are vital to us all. Niatero.org

Opportunity International

Opportunity International provides financial solutions and training to empower people living in poverty to transform their lives, their children’s futures and their communities. Opportunity.org

Water Mission

Water Mission is a Christian engineering nonprofit that builds safe water, sanitation, and hygiene solutions in developing countries and disaster areas. Watermission.org

Member Events

March 17: Ethiopia in Theory, Theory as Memoir

March 18: Using Talking Books for agriculture extension, disaster relief, and civic engagement // Amplio

March 26: Maximize Life Gala // The Max Foundation

Career Center

Director of Strategic Partnerships // Ashesi University Foundation

Associate Consultant // Gorman Consulting

Senior Technology Officer // Forest Stewardship Council (FSC)

Digital Communications Officer // Agros International

Global People & Culture Manager // Splash

Grant Writer // Snow Leopard Trust

Check out the GlobalWA Job Board for the latest openings.

GlobalWA Events

March 24: From Global to Local: Informing Seattle’s Pandemic Response – Virtual Program