By: Ulrike Hoessle

Rebecca Winthrop, senior fellow and director of the Center for Universal Education at Brookings. Photo: Ulrike Hoessle.

If you visit one of the poor communities around Lucknow in the Indian State of Uttar Pradesh, you might be amazed to see a school with a dirt floor, where teacher and students are discussing and applying the lessons from an educational video in the local language. That is how the non-profit Digital Study Hall, with support from Global Washington member Mona Foundation, mitigates the lack of highly trained teachers and provides high quality education to the poorest.

On Wednesday, March 7, Rebecca Winthrop from the Brookings Institute, one of the top think tanks in Washington D.C., presented to the Global Washington community her recent research on the kind of education children need to succeed. The event was part of Global Washington’s monthly issue campaign, which this year – in recognition of the organization’s ten year anniversary – have been exploring various challenges, and potential solutions, from the vantage of the next decade.

The tasks ahead are daunting, as Mahnaz Javid from the Mona Foundation described in her opening remarks, because – according to UN Education Commission – by 2030 over 800 million youth (around half of the global youth population) will reach adulthood without the required literacy and math skills to succeed in life.

The Brookings Institute calculated that with the current evolvement of educational systems, it will take 100 years to overcome this challenge. However, if global education systems instead opted for “leapfrogging,” they could rapidly speed up the process without following the path taken by other countries.

Other sectors have already demonstrated the value of leapfrogging. Financial inclusion has made progress, thanks to mobile banking, without building bank branches in every village. Winthrop believes the same accelerated progress can be attained within the education sector.

What would leapfrogging look like in education?

What would leapfrogging look like in education?

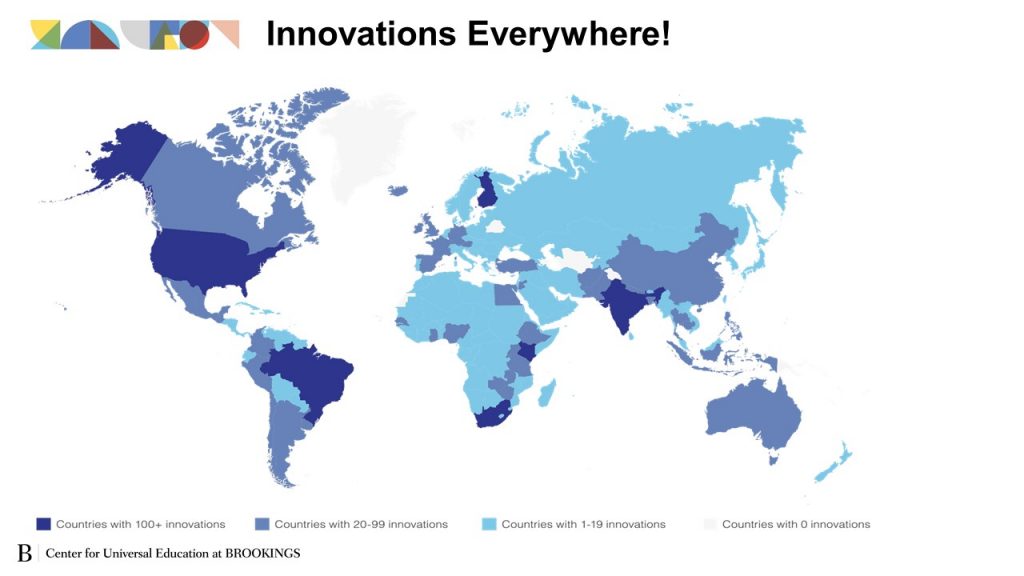

The Brookings Institute created a database that includes 3,000 education innovations from 166 countries. Contrary to the belief that education in general is following outdated models, education innovation is happening all over the world. Countries with the most education innovation include the USA, Finland, and countries like Brazil, South Africa, India, and Kenya (see Table 1). However, not every innovation is useful to leapfrog in education.

Which innovations help to leapfrog in education?

To answer this question, the role and the goal of education needs to be defined. Education is a social service, but, at the same time, it is a social process. Education is important not only for getting a job, but also for exerting one’s rights as a citizen and living a meaningful life. Education is a human right. Yet education is political, and at its core, ideological, as education conveys a society’s world views, values, and mission. Who goes to which schools? How do you teach history? To whom do you offer different tracks? Education can have its drawbacks, as well. It can, for instance, be used to manipulate young people who are vulnerable to propaganda (e.g. in Rwanda before the genocide took place).

What are the three important aspects about education?

- The benefits of mass schooling

It seems to many of its critics, that education has not changed in the last 250 years, when the first mandatory general education was introduced in 1763 in Prussia. While pointing out the flaws of the educational system, it is important to note the enormous societal benefits of mass schooling in our country and worldwide. Mass schooling was a radical enterprise in social equality. It contributed to increased health and life expectancy, and reduced child mortality. It played an important role in economic growth and in the reduction of poverty, especially absolute poverty, which is supposed to vanish completely by 2030. It allowed women to join the workforce, as schools were taking care of the children.

- The disparity of skills children are learning

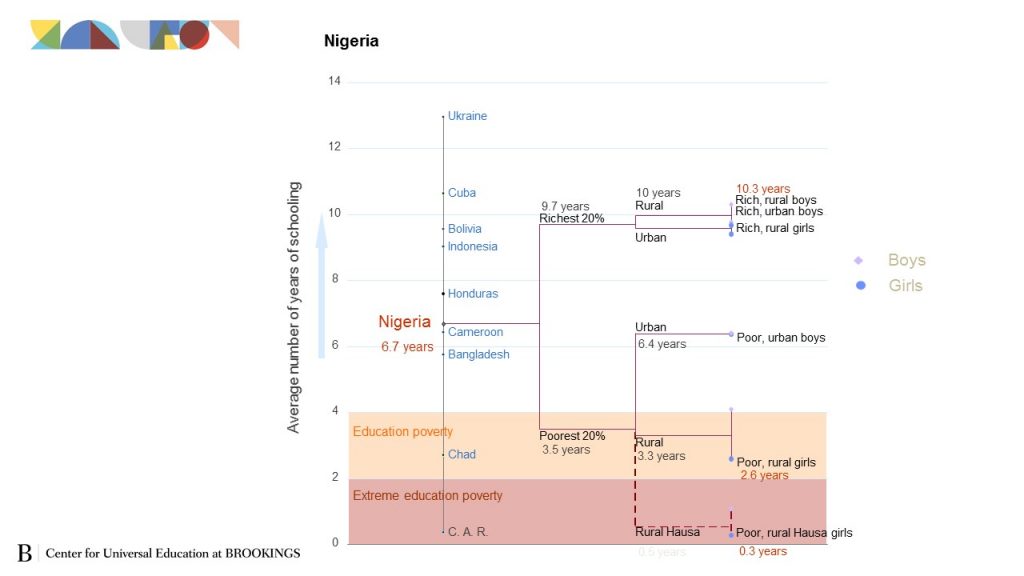

Within most countries, there is a disparity between outstanding education for the affluent and abysmal education for the poor. The U.S. for example, scores relatively low at the PISA Test, the OECD’s international student assessment. However, children in Massachusetts have access to the best education system in the world – on equal level with education champion Singapore, whereas children in Alabama are poorly served within their school system, which compares to countries such as Romania or Albania. The same applies to countries in the developing world. The example of Nigeria (see Table 2), shows that rich rural boys attend 10.3 years of school, compared to poor rural girls who attend school for only 2.3 years.

- The challenge of skills uncertainty

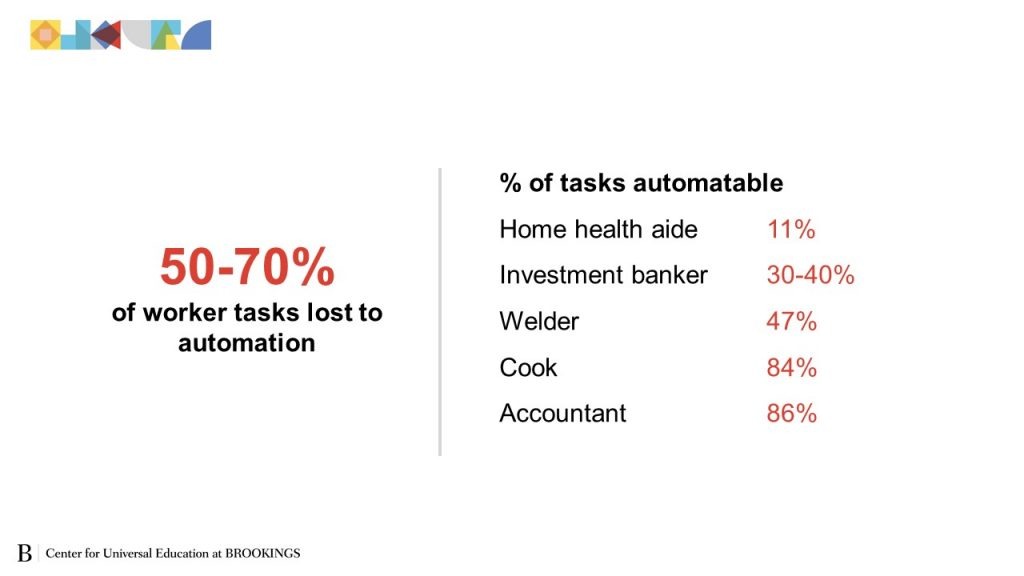

As our world is changing quickly, so are the skills required to succeed. Unlike the common notion that half of the jobs are going to disappear, in fact, it is only certain parts of the jobs that are going to be eliminated, such as routine cognitive or manual tasks that take place in a predictable environment. As shown in Table 3, 86% of an accountant’s tasks will be automated, compared to the 11% of a home health aide’s tasks. In addition, how much of a job will be automated depends also on the extent that technology has already permeated the industry.

Therefore, when educating young people, schools need to continue rigorous academic learning, while at the same time, teach skills for how to use this knowledge in different contexts over the students’ lifetime. Everybody must be a lifelong learner, as we do not know exactly what skills we need in the future and how we will apply them.

What is the goal of education?

The goal of education is for every child to have the academic knowledge and the breadth of skills to apply the acquired expertise in different settings.

How to reach this goal?

Teaching will still require lectures. In addition, a student-centered approach and more engaging pedagogy is required. Students still must learn multiplication tables, literacy, historical and scientific data facts, however, in the context of more complex issues that require critical thinking and problem solving. Education systems also need to rethink how to recognize and assess learning. Moreover, teaching might expand beyond people and places, and leverage technology and data. However, while technology can be used to enhance education goals, it is, in itself, not a panacea. Before using technology in education systems several questions need to be answered: What problems should be addressed? Can it be solved without technology? If not, do you have all components in place such as teacher training, adequate programming, and maintenance to meet your goals?

Although the non-profit sector is driving the education innovation, the best results are seen when – at the same time – governments are enabling the environment for scaling-up innovation, and for-profits are installing the necessary infra-structure, providing learning platforms or other educational services. Nevertheless, to address the concerns regarding the privatization of the education systems where only the affluent have access to high quality education, governments need to create a regulatory framework to mitigate negative effects.

There are numerous best practices for how to leapfrog in education. The Brookings Institute’s database shows that a successful education model cannot be a blueprint for another situation. Flexible adaptation which identifies the core components necessary for its success, is the most promising way to succeed in another area.

During the event, Rebecca Winthrop presented the following successful examples to leapfrog in education:

- The non-profit Pratham gave small groups of children in the rural areas in Uttar Pradesh tablet computers with educational content in Hindi and English for after-school learning, which helped to develop skills – from digital literacy to problem solving and teamwork.

- In most of the dispersed villages in the Brazilian state of Amazonia live less than 80 people, and most of the teachers who are licensed to teach secondary school did not want to leave the capital Manaus. To offer secondary education for all the students, the Amazonian government divided the teachers into two categories with equal status: lecturing teachers and mentoring teachers. The lecturing teachers, based in Manaus, broadcasted lessons, while the mentoring teachers, helped children with homework, co-operation with other students, and conflict-solving.

- The Seattle based non-profit educurious offers student-centered courses, projects and units in secondary education, while edmodo, a for profit company, provides a learning platform for students and teachers.

- The South-African non-profit Go for Gold offers disadvantaged high schoolers after-school training and pairs them with professionals for mentorship. After finishing high-school, the students gain their first professional experiences during as paid internship that helps them to make informed decision regarding their career choices. The next phase starts the professional training in the chosen career, and upon completion, partner companies hire the sponsored learners.

- One of Camfed – Campaign for Female Education – programs is to train young women to serve as mentors and peer teachers in rural African schools. These women, known as Learner Guides, deliver life and learning skills, information on sexual and reproductive health and offer psycho-social support. They work with schools, communities and district governments to keep children in school, and assist them to overcome their challenges. After finishing their assignment, Learner Guides can achieve a fast-track teacher certification, gain access to no-interest loans for opening their own businesses and to mobile phones to stay informed.

Many more insights, statistics, voices from the field and best practices are in the Brookings Institute’s report: Can we leapfrog? The Potential of Education Innovations to Rapidly Accelerate Progress.

Ulrike Hoessle taught “Women in the Developing World” and “Women and Globalization” at the University of South Florida, where she was confronted with the education disparity of Florida, when students described their schools in the poorer communities with broken windows, demolished furniture and lack of school material. She worked for foundations and non-profits on human rights, women’s rights and the environment in Africa and Latin America. In Seattle, she consults for WWS Worldwide on fundraising and organizational development. She has a M.A. in Cultural Anthropology and a Ph.D. in Political Science.