April 2018 Newsletter

Welcome to the April 2018 issue of the Global Washington newsletter.

IN THIS ISSUE

- Letter from our Executive Director

- Issue Brief: Women Hold Up Half The Cup: Gender Imbalances in the Production of America’s Most Popular Beverage

- Organization Profile: Standing on the “Impact-Led Edge,” Global Partnerships Invests in Greater Gender Equity and Agricultural Livelihoods

- New Member Profile: Fair Trade USA Shows How Social Impact and Coffee Quality Go Hand in Hand

- Welcome New Members

- GlobalWA Member Events

- Career Center

- GlobalWA Events

Letter from our Executive Director

Over the past several years, Global Washington has elevated the importance of the people and ecosystems that supply your daily cup of coffee. Coffee is predominantly grown in lower- and middle-income countries, and issues of income disparity and a changing global climate have a dramatic impact on the lives of people who make their living within the coffee industry.

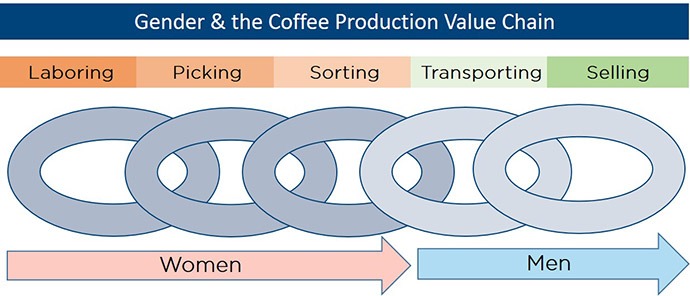

This year, Global Washington has taken a closer look at the disparity between men and women in the coffee supply chain. Although women play major roles in the early stages of coffee production – laboring in the field, harvesting coffee cherries, and processing the beans – men typically have the more lucrative roles of transporting and marketing the product.

Fortunately, several Global Washington members, such as Oikocredit, Fair Trade USA, Global Partnerships, and Starbucks, are working to close this gender gap and empower women in coffee-growing regions. So grab a cup of coffee (or tea, if that’s more your thing) and read about their stories below.

In addition to coffee, there are some other fascinating topics coming up. Global Washington will be partnering with Tableau Foundation and Seattle Pacific University to bring you an inside look at how data and technology are advancing the Sustainable Development Goals. Ms. Atefeh Riazi, the United Nations Chief Information and Technology Officer, will be speaking at a free public event on April 25. We are also partnering with the Seattle International Foundation and Pangea on May 16 to examine current issues of migration from Central America. And lastly, save the date of May 30 for an event with PATH and Days for Girls around World Menstrual Hygiene Day. More information on that event will be coming soon.

Kristen Dailey

Executive Director

Issue Brief

Women Hold Up Half The Cup

Gender Imbalances in the Production of America’s Most Popular Beverage

By Erika Koss

Woman picking coffee cherries in Matagalpa, Nicaragua. Photo: Gwenn Dubourthoumieu

At least two dozen pairs of human hands are involved in the production of a single cup of coffee. And many of those hands belong to women. This month, in honor of the Global Coffee Expo—the Specialty Coffee Association of America’s annual conference, held in Seattle from April 19-22—Global Washington has focused on an important issue within the coffee sector: Gender Equality.

In their internationally bestselling book Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide, Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn observe that if the moral challenge of the 19th century was slavery, and the 20th century’s battle was against totalitarianism, then the 21st century’s “moral challenge will be the struggle for gender equality around the world.”

A recent Specialty Coffee Association of America (SCAA) paper, “A Blueprint for Gender Equality in the Coffeelands,” summarizes some of the challenges that female farmer-producers face: “Overall, women earn less income, own less land, control fewer assets, have less access to credit and market information, greater difficulty obtaining inputs, and fewer training and leadership opportunities.”

A coffee farmer enjoys a cup of coffee at a tasting event (called a “cupping”), at the Nyampinga Cooperative, a women’s coffee cooperative in southern Rwanda. Photo: Erika Koss.

All the world’s coffee grows between Earth’s imaginary lines of latitude, the Tropic of Cancer (235 North) and the Tropic of Capricorn (235 South). Coffee aficionados know this zone as the “Bean Belt.” Within the more than 75 coffee-producing countries encompassed by the Bean Belt, there are significant economic disparities between male and female coffee producers.

The SCAA Sustainability Council finds that this gender gap in coffee value chains is most prevalent in four key areas: 1) distribution of labor, 2) income, 3) ownership, and 4) leadership and decision-making.

Many inequalities at the farm level are rooted in the “double burden” that women experience while managing both the farm and the household (which regularly includes at least several children and the elderly). Research shows that women perform most of the fieldwork, harvest work, and processing of coffee. Men often conduct the transport, export, and marketing of coffee—jobs that regularly provide a higher wage and take them away from the farms and their families.

One of the major challenges for rural women throughout Asia, Africa, and Latin America, are the customary land laws that prohibit women from owning their own land. As a Gender Issue Brief by Sweden’s development agency explains, less than 20% of agricultural women own their land, which is a major challenge since land ownership is linked to food security and poverty reduction.

In addition to identifying the major challenges in gender disparities, the SCAA provides several recommendations for reducing inequities between men and women in coffee:

- Include women and men equally in technical training: Traditionally, women in coffee have been excluded from technical trainings, but in recent years, this is starting to change thanks to organizations such as TWIN Trading. Their gender-inclusive approaches have proven successful in East Africa where mixed-gender programs focus on sustainable agriculture, financial management, and improving coffee quality.

- Promote community-driven initiatives that encourage balanced households: Working directly with farmer households to build greater gender balance takes time, but it can lead to transformative and lasting change in coffee-growing communities.An excellent example of this is the Gender Action Learning System (GALS), which was co-created by sociologist Linda Mayoux with a coffee cooperative in western Uganda, Bukonzo Joint. The methodology is designed to increase the visibility of female farmers along the coffee value chain and to enhance women’s decision-making power at the household level. GALS helps women gain greater control over assets and ensure they have more equal access to income within their households. Since the original project in 2004, GALS has been implemented in other coffee-growing communities including Colombia and Rwanda.

- Empower women and men equally with access to financial resources: Economic empowerment can only be achieved through increasing women’s access to land, income, and credit. If this can be achieved, it has the potential to dramatically improve coffee quality, increase productivity, and alleviate poverty.

- Research gender equality in the coffee industry: There is much we still do not know about the best ways to elevate women’s roles throughout the coffee supply chain. The International Women’s Coffee Alliance is a non-profit organization founded in 2003 that organizes women in coffee-producing countries. Their Research Alliance works toward increased awareness and funding for much-needed research regarding gender and coffee. In the last few years, their newly formed data-gathering initiative estimates that in three coffee-producing countries (Costa Rica, El Salvador, and Rwanda), there are more than 135,000 female coffee producers, approximately 30 percent of the total.

- Advocate for gender equality: We all have a role to play in helping address the gender pay gap in coffee production. In 2014, the Coffee Quality Institute founded the “Partnership for Gender Equity”—a set of principles created to guide the coffee industry forward.The women, whose hands nurture coffee seedlings, pick coffee cherries from trees, and sort “parchment beans” after processing are vital to a complex global supply chain. But there are an uncounted number of women involved in exporting and importing green coffee beans, as well as roasting, grinding, packaging, and brewing.It is time women at all these stages of coffee production are recognized and fairly compensated. Because from farmer to barista, women hold up—at least—half the cup.

***

By increasing women’s access to land, credit, market information, agricultural inputs, and training, the following Global Washington members are working to ensure greater gender equity in coffee production.

Eastern Washington University professor, Julia Smith, teaches anthropology and researches the high-end coffee market in Costa Rica. In her first encounter with women’s work in coffee in the 1990s, Smith observed that women worked harder than men during the coffee harvest. Day after day, they started early in the morning, preparing meals for the family, then picked coffee all day, and finally finished up by washing clothes and collapsing into bed. Today, more women are taking on leadership roles in producing coffee for the specialty coffee market, making decisions about what varieties to grow, how to process it, and how to sell it.

Fair Trade USA is a nonprofit organization and the leading certifier of Fair Trade products in North America. Their rigorous standards around the production of coffee help protect fundamental human rights, ensure safe, healthy working conditions, protect the environment, and deliver additional economic resources to producing communities. In addition to these requirements, Fair Trade also sets minimum prices to protect farmers when the market dips too low, and ensures that producers earn additional Community Development Funds to address their pressing needs. Many groups vote to spend this money on projects that benefit women, like cervical cancer screenings, scholarships, child care centers and microloans for income diversification.

Global Partnerships is an impact-led investor whose mission is to expand opportunity for people living in poverty. The organization invests in social enterprise partners who empower people to earn a living and improve their lives. Over the last 24 years, Global Partnerships has impacted more than 8.9 million lives in 19 countries across Latin America, the Caribbean and sub-Saharan Africa as a result of deploying $287 million in impact-led investments to 118 partners. Some of these partners include agricultural businesses and cooperatives that help smallholder coffee farmers, both women and men, increase their incomes and strengthen their economic well-being.

Landesa is a global organization that champions secure land rights for rural women and men. The majority of the world’s poorest people share three traits: they live in rural areas, rely on land for their livelihoods, and do not have secure rights to own, access, or use that land. Women are especially burdened. Although women comprise a large portion of the world’s agricultural labor force, women generally have weaker rights to land when compared to their male counterparts. Yet, secure land rights are a key factor in creating an enabling environment that increases women’s participation, profit, and benefit in agriculture and food systems. To close this gender gap, Landesa works with governments, civil society, and the private sector to conduct research and develop gender equitable laws and programming to empower women in emerging economies with secure land rights.

Oikocredit US promotes and facilitates the global work of Oikocredit International, a cooperative social investor that maximizes social and environmental impact through targeted investments to serve vulnerable groups. Led by a dedicated agricultural unit, Oikocredit invests across the coffee value chain with 41 partners in 12 countries. Oikocredit supports farmers with capacity building grants, education, and network services. In all investments, Oikocredit seeks to enhance women’s participation in leadership and to address women’s empowerment at the local level by supporting partners who have dedicated services and programs to address gender equality.

Seattle University was the first Fair Trade University in the Pacific Northwest. As part of the University’s journey to garner Fair Trade certification, Seattle University collaborated with the Universidad Centroamericana (UCA) – Managua to develop a new fair trade coffee. In partnership with farmers in the Nicaraguan cooperatives, they developed Café Ambiental, SPC, a student-run social enterprise. Other projects included developing a more sustainable way to treat coffee wastewater, and establishing a scholarship fund for coffee farmers’ children. Most recently, they collaborated with a gender-balanced cooperative in Penãs Blancas that promotes greater participation of women and young people.

Starbucks Since 1971, Starbucks Coffee Company has been committed to ethically sourcing and roasting high-quality arabica coffee. Today, with more than 27,000 stores globally, Starbucks is the premier roaster and retailer of specialty coffee in the world. In March, the Starbucks Foundation announced a partnership strategy to empower at least 250,000 women and families in coffee, tea and cocoa growing communities by 2025, including a new global partnership with the Malala Fund to promote girls’ education and expand leadership opportunities for young women in India and Latin America. The partnership adds to Starbucks’ ongoing social investments worldwide with organizations like Mercy Corps, Eastern Congo Initiative, and Heifer International.

Thriive’s mission is building shared prosperity in vulnerable, global communities. The organization makes pay-it-forward loans of up to $10,000 to ambitious small business entrepreneurs to grow their businesses and create desperately needed jobs. Unlike a bank or microfinance loan, ThriiveCapital loans are not repaid in cash, but by business donations of an equivalent value of job training, income-enhancing products, or basic necessities to disadvantaged community members. Thriive supports many different types of businesses, including coffee growers, roasters, and retailers in Nicaragua, Guatemala, Kenya, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

Woodland Park Zoo Since 1996, Woodland Park Zoo’s Tree Kangaroo Conservation Program (TKCP) has worked with the communities of Yopno-Uruwa-Som (YUS) to protect the endangered tree kangaroo and its rain forest habitat in Papua New Guinea. In 2009, TKCP partnered with the indigenous YUS landowners and their families to help address economic challenges. In collaboration with Woodland Park Zoo and Seattle-based coffee roaster Caffe Vita, the people of YUS have sold more than 75 tons of their shade-grown YUS Conservation Coffee directly to the international market. Coffee farming in YUS is a family affair, with both men and women playing important roles in its production. TKCP strives to promote gender equity by engaging women in technical trainings, management decision-making, and access to household income.

Erika Koss is a PhD candidate in International Development Studies at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where her research examines the geopolitics of coffee's supply chain of coffee with a focus on gender justice and climate change.

Organization Profile

Standing on the “Impact-Led Edge,” Global Partnerships Invests in Greater Gender Equity and Agricultural Livelihoods

By: Joanne Lu

Woman farmer. Photo: Global Partnerships

For Global Partnerships (GP), impact at the household drives every investment. And often, that means investing in women.

GP was founded in 1994 as a grant-making nonprofit by Bill and Paula Clapp, whose vision also included the founding of Global Washington. GPs’ mission then – as it is today – is to expand opportunity for people living in poverty. Twelve years later the organization pivoted to being an impact-led investor to reach more people living in poverty.

Impact investments are made with the intention to generate positive social and environmental impact as well as a financial return. But GP isn’t just an impact investor. GPs’ Chief Impact & Research Officer, Peter Bladin, points out that the organization is an “impact-led investor.” Meaning their investments in social enterprise partners are first and foremost focused on making a sustainable positive impact in the lives of people living under $3.20 a day in sub-Saharan Africa or $5.50 a day in Latin America and the Caribbean (The World Bank’s regional poverty lines).

GP’s social enterprise partners currently span 19 countries. They also fall within GP’s 13 investment initiatives, including women-centered finance with education, urban sanitation, cookstoves, solar lights, health clinics, smallholder farmer market access and others.

“It’s a very broad spectrum, but it’s all driven by entities delivering products and services that are meaningful for households living in poverty,” Bladin said.

The organization launched each of its initiatives after extensively researching the most meaningful market-based solutions that would have a sustainable impact at the household level in the regions it serves. These initiatives are the guidelines for the types of social enterprises (or “partners”) GP invests in.

“Our Initiatives carefully focus on who the target audience is, such as women under a certain poverty level, and what is delivered to them, such as loans plus education,” Bladin said. “This very focused definition on the “who” and the “what” allow us to better understand the expected outcome. We use research, academic and otherwise, that has defined the outcomes in similar situations. By using this approach, it allows us to be more confident in the expected outcome. We also test into these outcomes with select case studies to verify we see the same positive impact.”

Farming family. Photo: Global Partnerships.

And much of this research demonstrates that one of the most effective ways to make an impact is by investing in women. Evidence shows that women invest as much as 10 times more in the health and well-being of their families. A child is 20 percent more likely to survive and thrive if it is born into a household in which the mother manages the budget. In addition, when women have the same amount of land as men, there is a 10 percent increase in crop yields. Gender equality in agriculture could also reduce the number of undernourished people globally by as much as 150 million.

That’s why all of GP’s investments are benefiting women, even if it’s not within one of their exclusively women-centered initiatives. For instance, even though women do most of the field work and make up nearly half of all smallholder farmers, contextual barriers make it challenging to work directly with women in agriculture. But by investing in enterprises that address the many needs of smallholder farmers – not just improved inputs like fertilizer and seeds, but also credit, technical assistance, and improved market access – GP is able to invest at various points where the supply chain fails to reach and create value for women.

As an example, Aldea Global is one of GP’s partners in Nicaragua that works with lawyers to help farmers wade through the complicated legal process of land acquisition. Once all the correct documents are filed with the local registrar, Aldea Global presents the farmer with a new land title along with a cash grant. Although they don’t work exclusively with women, they do provide support to women, many of whom, as first-time land owners, are able to transform their lives (and those of their families) with newfound independence, self-esteem, and access to financial products and services.

Because coffee is such a major cash crop where GP invests, many of its partners within the “smallholder farmer market access” initiative focus on coffee cooperatives that supply to specialty brands. A couple of its partners – Aldea Global and APROCASSI in Peru – have very successfully engaged with women-only coffee co-ops. APROCASSI’s women’s group, for example, supplies beans to Allegro Coffee, which is sold at Whole Foods.

Still, GP acknowledges that moving agricultural communities toward more gender equity is a slow process that requires shifts in social, cultural, economic and political norms.

“We think that private capital will play a critical role in unlocking opportunities while legal and cultural norms shift, allowing more women to engage in the market,” Bladin said.

As they work toward that, Bladin says GP also has plans to continue expanding. They have reached almost 10 million people since 1994, and Bladin says they’re on track to reach 30 million by 2024. He also hopes they’ll have significantly more outstanding capital in the next decade to invest in enterprises that are scaling up or just getting started.

But perhaps more importantly, Bladin says GP wants to encourage more investors to join them on the “impact-led edge.”

“We want to stay on that edge,” he said. “And we want to raise the profile of telling people there is an edge – that even among impact investors, you can have more of an impact if you’re not exclusively focused on financial returns.”

New Member Profile

Fair Trade USA Shows How Social Impact and Coffee Quality Go Hand in Hand

By: Joanne Lu

Marliah, a member of a coffee co-op in Aceh, the northern-most province in Sumatra, holds freshly harvested coffee cherries. Photo: Bennett Wetch. © 2015 Fair Trade USA.

Coffee has been at the center of Fair Trade USA since its beginning.

When the nonprofit organization launched in 1998, it had one product – coffee – and just a handful of partner companies. Now, as the leading third-party certifier of Fair Trade products in North America, Fair Trade USA works with more than 1,300 companies to source products and ingredients that foster sustainable livelihoods for farmers and workers and protect the environment.

In its recently announced sustainability standards, the Seattle-based co-op REI even listed Fair Trade USA as a preferred certification for its suppliers.

In addition to coffee, Fair Trade certifies and promotes more than 30 product categories from around the globe, including tea, produce, sugar, cocoa, spices, seafood, apparel, home goods and more. According to the organization, Fair Trade USA and its partners have helped deliver over $500 million in additional economic impact to farmers, workers, and fishermen since 1998.

It all began with a coffee cooperative in Nicaragua. Current President & CEO Paul Rice founded Fair Trade USA after spending 11 years in Nicaragua, where he organized cooperatives and trained farmers. During that time, he helped launch the country’s first Fair Trade organic coffee export cooperative, PRODECOOP. The success of PRODECOOP showed Rice just how transformative it can be when the most vulnerable people along a value chain are treated with respect.

Maria Elva Correa Torres, 40, shows her coffee plants in Cajamarca, Peru.

Photo: James A. Rodriguez. © 2015 Fair Trade USA.

That’s because the length and complexity of traditional value chains often allow unsafe and unfair practices to go unnoticed by consumers and the businesses that sell to them. When companies drive down prices to compete, it’s the farmers and workers whose livelihoods are often cut.

Coffee, in particular, goes through a long and complex process to get from farm to mug: Farmers choose (or are given) trees. They determine where to plant them. The coffee grows as a cherry on a tree. Then, the coffee is harvested – and immediately, its quality begins to degrade. The seed – or “bean” as it’s usually called – is removed from the cherry. The seed is fermented, dried, dried some more, then stored. After a bit, parts of the seed are removed, and it’s stored again. Then, it’s sold, shipped and packaged to sit in in a warehouse, before it’s purchased by a roaster. The coffee then goes through a roasting process, before it’s stored again and bagged. Only then is the coffee ground and brewed for consumption.

According to Fair Trade USA’s Director of Coffee Supply Chain Colleen Anunu, the value addition throughout the whole process sets coffee apart from other cash crops.

“All along these lines there are specific decisions that are made that can impact the quality of the coffee by the time that you drink it,” Anunu said. “It’s really a complex and unreliable trade scheme.”

Although the commercialization of Fair Trade goods began in the 1940s mostly as handicrafts sold in churches and fairs, specialty goods like coffee and chocolate have become prime products in the Fair Trade movement. That demand bolsters the global effort of producers, consumers, certifiers, brands, NGOs and academics to build a more just, transparent and equitable system of global trade. Whereas Fair Trade was initially just focused on rebalancing power dynamics so producers could have more determination in their products and sales, quality and the ability to know the suppliers to some extent now supplement the model.

Fair Trade USA works toward that ideal at various points along the value chain. To make sure the farmers and workers who are producing Fair Trade Certified products are being paid a fair and often above-market price, the organization audits transactions between businesses that sell Fair Trade Certified items and their international suppliers. Additionally, the organization educates consumers about Fair Trade and its impact.

But perhaps the most direct way Fair Trade USA is working to achieve its mission is through its certification process. Producer communities must meet the organization’s strict social, environmental, and economic standards, such as safe working conditions, no child or forced labor, no use of harmful chemicals, and proper waste disposal. When farmers and workers achieve certification, they earn an additional amount of money, called the Fair Trade Premium, with every sale. This fund is then used to address needs within the community.

“The important part is that farmers and workers vote together on how to use this money,” Fair Trade USA’s Director of Marketing and Communications Jenna LeDoux said. “They’re solving their own problems on their own terms.”

The Gumutindo Coffee Cooperative in Uganda voted to use some of its Fair Trade community development funds to repair the roofs of the local school buildings after a big storm, as well as to purchase school desks. The community development funds also support teacher training.

Photo: Bennett Wetch. © 2015 Fair Trade USA.

Although Fair Trade is a powerful strategy for economic empowerment, there continues to be a discussion on how to promote more gender equity. Especially in long, complex value chains like coffee, women do a majority of the labor but are often overlooked in the distribution of benefits. They do the housework and in some areas a majority of the farm work, as well, but because their husbands and sons primarily own the land and market the product away from home, women don’t usually have a say in how the money is spent or saved. Training, too, is often conducted for landowners who don’t put the learning into practice, because women are often the ones doing the labor.

Even in Fair Trade co-ops, gender imbalance can be prevalent. Many co-ops don’t recognize women as full members, as membership is partly based on land ownership. However, Anunu pointed out that there are levers within the Fair Trade model that are utilized to promote women’s economic and social empowerment, such as the Fair Trade Premium. The funds might be used as an additional payout to farmers, or it may go toward new warehouses, water treatment facilities, smokeless cook-stoves, women’s health screenings or whatever else the community wants the money to be used for.

Fair Trade standards are also applicable where hired laborers (farm and factory workers) are concerned. For instance, Fair Trade has strict standards around sexual harassment, maternity leave, and health and safety, and it also ensures that the Fair Trade committee is representative of the workforce. This means that if women are employed on a farm, women must be represented in the decision-making process around the Fair Trade Premium fund.

If women are able to receive training along with men, they can increase the profitability of products like coffee by engaging in practices that improve quality. Evidence has also shown that when women have a say in how income is spent or saved, the whole household benefits.

Overall, from a production perspective, Fair Trade is driving change through social and environmental standards. On the consumer side, Fair Trade awareness also is at an all-time high – at 63 percent of the U.S. population, according to Fair Trade USA.

But for coffee specifically, Anunu hopes to see more of a shift in the industry over the next decade toward an understanding that quality coffee and Fair Trade coffee aren’t mutually exclusive.

“Direct trade relationships between roasters and growers too often narrowly focus on the coffee quality and just assume there will be positive social impact because of the higher prices,” she said. In fact, these trading schemes can skip important shared values and assurances that are the basis for the Fair Trade model.

“You can’t have social impact and not focus on coffee quality, and vice versa,” she said. “They need each other to thrive.”

Welcome New Members

Please welcome our newest Global Washington members. Take a moment to familiarize yourself with their work and consider opportunities for support and collaboration!

Friendly Water for the World

Friendly Water for the World expands global access to low-cost clean water technologies and information about health and sanitation through knowledge-sharing, training, community-building, peacemaking, and sustainability. It empowers communities abroad to take care of their own clean water needs. friendlywater.net

Northwest Immigrant Rights Project

Northwest Immigrant Rights Project promotes justice by defending and advancing the rights of immigrants through direct legal services, systemic advocacy, and community education. Northwest Immigrant Rights Project strives for justice and equity for all persons, regardless of where they were born. nwirp.org

Breakthrough

Breakthrough is a global human rights organization working to drive the culture change needed to build a world in which all people live with dignity, equality, and respect. Working out of centers in the U.S. and India, Breakthrough uses a potent mix of media, arts, and tech to reach people where they are and inspire them to take bold action to challenge the status quo. The organization often views the most crucial issues of our time through the lens of gender, because it believes that promoting equality for all genders is a pathway to promoting the human rights, and the humanity, of all people. Since 1999, Breakthrough has also worked to promote immigrant rights, racial justice, and the rights of people living with HIV/AIDS. Us.Breakthrough.tv

Fair Trade USA

Fair Trade USA is a nonprofit organization that promotes sustainable livelihoods for farmers and workers, protects fragile ecosystems, and builds strong, transparent supply chains through independent, third-party certification. Its trusted Fair Trade Certified™ seal signifies that rigorous standards have been met in the production, trade and promotion of Fair Trade products from over 50 countries across the globe. fairtradecertified.org

Vulcan

Vulcan Inc. is the engine behind philanthropist and Microsoft cofounder Paul G. Allen’s network of organizations and initiatives. Empowered by Paul’s vision to make a positive difference in the world, Vulcan works to be a catalyst for change. The organization is committed to improving our planet through catalytic philanthropy, inspirational experiences, and scientific and technological breakthroughs. vulcan.com

Member Events

April 18: Greater Seattle Business Association // Business Development Workshop: How to be a seller on Amazon

April 18: World Affairs Council // Global Classroom: Taiwan in the Balance

April 21: OneWorld Now! // Get Global Youth Conference

April 23: Washington Nonprofits // Finance Unlocked for Nonprofits

April 24: University of Washington and Landesa // Roy Prosterman Lecture and Sustainable International Development Alumni Celebration

April 26: University of Washington // Panel | Women’s Economic Rights in India, Liberia, and Myanmar: Issues and Interventions

April 28: Washington Nonprofits // TACOMA: Tools for Running an Effective Nonprofit

May 2: Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce// Women in Business & Leadership Initiative – Spring Symposium 2018

May 2: Washington Nonprofits // ONLINE: 10 Tips to Use Video to Fuel Your Fundraising and Marketing

May 7: Seattle University // Peter L. Lee Endowed Lecture in East Asian Culture and Civilization

May 8: Washington Nonprofits // Social Media 101 for Nonprofits

Career Center

Highlighted Positions

Associate Scientist, Intellectual Ventures

Program Officer, International Visitor Program, World Affairs Council

Communications Coordinator, Seattle International Foundation

Innovation Manager, Impact Lab, PATH

Check out the GlobalWA Job Board for the latest openings.

GlobalWA Events

April 17: Networking Happy Hour with Friends of GlobalWA, WGHA and World Affairs Council

April 19: Women Hold Up Half the Cup – Empowering women in coffee-growing regions of the world

April 25: How data and technology can advance the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)