The following selection from her remarks includes the parts that are relevant to global development policy. Click here to read the full speech on the State Department website.

SECRETARY CLINTON: Good evening. This is such a great treat, personally, to be back in San Francisco. And it’s somewhat disconcerting, because this is only the third place in the United States that I have spoken, since I became Secretary of State and — (laughter) — (applause) — the first place, which some may question whether it still is in the United States is, of course, Washington — (laughter) — where I have spoken several times and in Hawaii on my way to Asia. I have been invited to come to the Commonwealth Club many times over the years and was unable to accept that kind invitation, but I thought it would be an appropriate time for me to have this conversation.

Now, mostly this is going to be a conversation, but I wanted to just make a few points, because I think it’s important to give you a bit of an overview of what we’ve been trying to do since January, 2009. Clearly, for me as Secretary of State, it is a primary mission to elevate diplomacy and development alongside defense so that we have an integrated foreign policy in support of our national security and in furtherance of our interests and values.

Now, that seems self-evident when I say it tonight here in this gathering, but it’s actually quite challenging to do. It’s challenging for several reasons. First, because the diplomacy of our nation, which has been from the very beginning, one of the principal tools of what we do, has never been fully and well understood by the general public. It appears in the minds of many to be official meetings mostly conducted by men in three-piece suits with other men in government buildings and even palaces to end wars and resolve all kinds of impasses. And of course, there is still that element, not only with men any longer, but nevertheless, the work of diplomacy is still in the traditional mode.

But it is so much more today, because it is also imperative that we engage in public diplomacy reaching out to not just leaders, the citizens of the countries with whom we engage, because even in authoritarian regimes, public opinion actually matters. And in our interconnected world, it matters in ways that are even more important. So we have tried to use the tools of technology to expand the role of diplomacy.

Similarly, with development, I have long been passionate about what our assistance programs mean around the world, how they represent the very best of the generosity of spirit of the American people. And USAID, which was started with such high hopes by President Kennedy, did so much good work in the 1960s and ’70s. The Green Revolution, the absolutely extraordinary commitment that the United States, our researchers, and our agricultural scientists made to improving agriculture around the world, transformed the way people were able to feed themselves and to build a better future.

Then over time, USAID became hollowed out. It became truly a shadow of its former self. It became not so much an agency of experts as a contracting mechanism. So the work that used to be done by development experts housed in the U.S. Government became much more a part of contracting out with NGOs here at home and around the world. So the identity, the reputation of USAID no longer was what it needed to be.

So when I came into the office of Secretary of State, I sort of followed the example of the Defense Department which has for many years conducted what’s called the Quadrennial Defense Review. And when I was in the Senate, I served on the Senate Armed Services Committee and I realized what a powerful tool that QDR was. Because it provided a structured planning experience internally for the Defense Department that would then be shared throughout the executive branch, presented to Congress and to the public, and help to guide what it was that our country would be doing for the next four years when it came to the nation’s defense.

So I embarked upon the first ever Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review which will come out by the end of this year. It’s quite an undertaking to do it for the first time, because you have to question all of your assumptions and your presumptions and try to figure out how best to present what we do in the State Department and USAID, for which I am also responsible, and to set forth a vision with strategies and objectives that will take us where we want to go as a nation. I’m also working very hard to make it not just bipartisan, but nonpartisan, because certainly our national commitment to defense is nonpartisan and has bipartisan support in the Congress and I want the same for diplomacy and development.

One aspect of what we’re doing to promote diplomacy and development that is quite new and has special relevance for the Bay Area in Northern California is our emphasis in innovation and our use of technology. We have been working very hard for the last 20 months to bring into the work we do the advances that many of the companies and the innovators, entrepreneurs here in California have brought to business, have brought to communications in particular.

Innovation is one of America’s greatest values and products and we are very committed to working with scientists and researchers and others to look for new ways to develop hardier crops or lifesaving drugs at affordable costs, working with engineers for new sources of clean energy or clean water to both stem climate change and also to improve the standard of living for people. Social entrepreneurs who marry capitalism and philanthropy are using the power of the free market to drive social and economic progress. And here we see a great advantage that the United States that we’re putting to work in our everyday thinking and outreach around the world.

Let me just give you a couple of examples, because the new communication tools that all of you and I use as a matter of course are helping to connect and empower civil society leaders, democracy activists, and everyday citizens even in closed societies.

Earlier this year, in Syria, young students witnessed shocking physical abuse by their teachers. Now, as you know, in Syria, criticism of public officials is not particularly welcome, especially when the critics are children and young people. And a decade earlier, the students would have just suffered those beatings in silence. But these children had two secret weapons: cell phones and the internet. They recorded videos and posted them on Facebook, even though the site is officially banned in Syria. The public backlash against the teachers was so swift and vocal that the government had to remove them from their positions.

That’s why the United States — (applause) — in the Obama Administration is such a strong advocate for the “freedom to connect.” And earlier this year, last January I have a speech our commitment to internet freedom, which, if you think about it, is the freedom to assemble, the freedom to freely express yourself, the right of all people to connect to the internet and to each other, to access information, to share their views, participate in global debates.

Now, I’m well aware that telecommunications is not any silver bullet, and these technologies can also, as we are learning, be used for repressive purposes. But all over the world we see their promise. And so we’re working to leverage the power and potential in what I call 21st century statecraft.

Part of our approach is to embrace new tools, like using cell phones for mobile banking or to monitor elections. But we’re also reaching to the people behind these tools, the innovators and entrepreneurs themselves.

For instance, we know that many business leaders want to devote some of their companies’ expertise to helping solve problems around the world, but they often don’t know how to do that, what’s the point of entry, which ideas would have the most impact. So to bridge that gap, we are embracing new public-private partnerships that link the on-the-ground experience of our diplomats and development experts with the energy and resources of the business community.

One of my first acts as Secretary was to appoint a Special Representative for Global Partnerships and we have brought delegations of technology leaders to Mexico and Colombia, Iraq and Syria, as well as India and Russia, not just to meet with government officials, but activists, teachers, doctors, and so many more.

This summer, an entrepreneur named Josh Nesbit from Frontline SMS, which designs communications tools for NGOs, joined a State Department delegation to Colombia. And on the trip he learned first-hand about one of the biggest problems in the country’s rural areas: injuries and deaths from unexploded land mines. He was so moved that this month he is going back to work with the government, local telecom companies, and NGOs on a mobile app that will allow Colombians to report the location of land mines so they can be disposed of safely.

Similarly, in Washington, we are bringing together groups of experts from various fields to join us in working on big foreign policy challenges. Last year we held our first TED@State conference. Just last week, Cherie Blair and the cell phone industry around the world, we convened a group to talk about how to advocate for girls and women to get access to cell phones. It’s a new initiative called mWomen, which will work to close the gender gap that has kept mobile phones out of reach for 300 million women in low- and middle-income countries.

At USAID — (applause) — we’re pursuing market-driven solutions that really look to see how to involve the business community and we just unveiled a new venture capital style fund called Development Innovation Ventures, which will invest in creative ideas that we think can lead to game-changing innovations in development. As part of our first round of financing, the fund has already invested in solar lighting in rural Uganda, mobile health services in India and an affordable electric bicycle that doubles as a portable power source.

The door is open to each and every one of you. I just met with a group from Twitter and I know that there area a million ideas that are born every day here. And if you have a good idea, we will listen. Because despite all the progress that we’ve made, we cannot take for granted that the United States will still lead in the innovation race.

We’re working to foster innovation at home and promote it abroad and President Obama has set the goal of devoting 3 percent of our gross domestic product to research and development and to moving American students from the middle to the top rankings in math and science, and ensure that by — (applause) — by 2020 we regain the position that we held for decades which we have lost; namely having the highest proportion of college graduates in the world.

And we need to make sure — (applause) — that American companies have the incentives they need to keep innovating. Companies must be assured that if they sell their products around the world, they do so without fear of piracy, that their intellectual property rights are protected and that the rule of law applies to everyone equally.

In our efforts over the last 20 months, we’ve been raising these issues at the highest levels across the globe. But we can’t do this alone. We need your help. And one way to contribute is by joining one of the new public-private partnerships I’ve described. We recently launched a new mentoring program called TechWomen that pairs accomplished women in Silicon Valley with counterparts in Muslim communities around the world. Women from these Muslim communities will spend five weeks gaining skills and experiences here in California. And just this week Twitter joined the program, and I hope many more will follow.

I also urge you to become involved with the social entrepreneurship movement, which is proving every day that there is money to be made through socially responsible investments. Putting financial and social capital to work is one of our goals. And next year we will host a conference for social entrepreneurs and investors in Washington, called SoCap — s-o-c-a-p — @State.

But most of all, we just want to let you know that when I talk about diplomacy and development in the 21st century, it’s not just what I do when I go off to Asia or Africa or Latin America or anywhere else; it is what we all do. Because I’m convinced that it is not only our connections through governments that will really chart the course of the 21st century, but indeed, it is the people-to-people connections. And there isn’t anyone anywhere who doesn’t know that our free dynamic society with so many opportunities for people doesn’t in some way hold out both promise and example for them.

And so whether you care about Haiti where we have worked from the very beginning of the disaster there to help with relief, recovery, and now, reconstruction; or whether you care about the violence in Mexico from the drug cartels and we’re helping to put together an anonymous crime reporting tip line so that citizens can report what they see and learn without fear of being exposed; or whether you care about national treasures like those in Iraq that were endangered over the last several years — so we worked with the Iraq National Museum and Blue State Digital and Google Maps and Google Street View and Google to send engineers to Baghdad to take 15,000 pictures to create a catalogue of the antiquities that were in danger of being lost; or whether you care about empowering young people or mobile justice in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the site of some of the most gender- and sexual-based violence in the world history where we’re planning a project to use technology to facilitate justice for survivals of violence in Eastern Congo; or whatever it is you care about, we want you to know that there is a place for you to become involved and work with us at the State Department and USAID. Because I believe strongly that you each can play a role in helping us chart a better future. Thank you all very much. (Applause.)

QUESTION: Madam Secretary, thank you for coming. Welcome to the Commonwealth Club.

SECRETARY CLINTON: Delighted to be here.

QUESTION: You know how to draw a big audience, for sure. (Laughter.) You mentioned freedom in your remarks and Freedom House is an organization that does an index of freedom around the world and this year they came out and said there have actually been four years of decline in freedom around the world, which is the worst that they’ve seen in the 40 years they’ve been measuring freedom. They say that half the world is free, half — a quarter is partly free and a quarter is not free. So given all the things you’ve talked about, the trend of freedom seems to be going in a non-positive direction.

SECRETARY CLINTON: Well, I think that there is a worrisome trend that despite a lot of the advances that I was just talking about and the tools of communication that have such potential for empowering and liberating people to pursue their own goals in life, there are some counter trends. And we see efforts by government to prevent the accessed information that we believe is a fundamental value and freedom. We see governments that believe democracy consists of having one election and that’s it. And so a lot of the progress that was being made to promote democracy was not firmly embedded in the societies that had no experience in what it means to have a democracy — the habits of the heart, the establishment of institutions from a free press to an independent judiciary on protection of minority rights.

We also see that even in very developed democracies that have always prized freedom and the right to privacy, there are new threats such as the threat of terrorism that have caused governments around the world to become much more cautious and careful and that try to, in their effort to keep their citizens safe, impose certain rules and regulations that does chip away at an expansive view of freedom. So we know there’s a lot that is happening that is worrisome. But I still believe that the big — as opposed to the headlines, the trend lines are positive, but you can’t take them for granted, which is why we’re working so hard.

QUESTION: Thomas Friedman believes, of the New York Times, that there is a correlation with the price of oil and freedom around the world, that high oil prices — and Freedom House says the Middle East is where they are most troublesome. Do you think that the price of oil and what he calls petrol dictators, does that have an influence on freedom or is that not one of the factors that you —

SECRETARY CLINTON: Well, I think that there has been a correlation between the hunt for natural resources, primarily oil, and the attitudes taken by governments that have those resources to husband them and protect them. But I don’t think it’s just that. There are other aspects of societies that are rooted in their own history and culture that contribute to that.

But it is fair to say that there is a so-called oil curse. Because when countries discover oil, start marketing that oil, if they’re not thoughtful, if they’re not visionary, very often it becomes a small elite that benefits from it. The benefits are not broadly shared and the progress of democracy and freedom is halted. And the necessity for democracy to deliver services for people in order to maintain the support for a new democracy is unfortunately diminished. So there is certainly a connection. In some places it’s more obvious than others.

QUESTION: You talked about development as a key priority. Recently the United States announced a directive on global development that was aimed on market forces, self-reliance. How is this going to be different? You said that the ’70s were the glory years for economic or aid, foreign aid, and then aid lost its way. So how is this really going to be different from past reforms of the aid mechanism?

SECRETARY CLINTON: Well, it’s going to be a much more comprehensive effort to rebuild USAID as the premier development agency in the world. And in order to do that, we have to have a clear focus of our mission. And in the President’s speech at the United Nations a few weeks ago in connection with the Millennium Development Goals Summit, the President laid out a focus on trying to enhance economic growth, build middle classes around the world, because that does correlate with stability and increasing political freedom and democracy historically. It also means, though, doing a really hard scrub of USAID. And Dr. Raj Shah, who is the new Administrator, and I are working very closely to really change procurement policies, personnel policies, try to streamline the delivery of aid.

I’ll give you an example. We have 24 different agencies in our government that provide some sort of aid, some sort of development aid. And it makes it difficult to speak with an authoritative voice in a country and to avoid redundancy and reduplication. So if you’re an African woman in a rural part of a country in Sub-Saharan Africa and perhaps you are HIV positive. Well, you may be able to go to one place and antiretrovirals from PEPFAR. You may go to another place and with a USAID program get your children immunized. You may go to another place to try to get healthcare for pregnancy and labor and delivery. And you may go to another place an try to get help with your crops to get fertilizer and see and we have all these parallel structures.

And the problem is that if you’re an ambassador in a country or if you’re the Secretary of State, if you call everybody who works either directly for the United States Government or on contract from the United States Government who is working in development as I have done in the past. I can guarantee you that the people in the room often don’t even know each other and rarely work with each other. And at some point, that is not a sustainable model, because in our own tough budget times, I have to be able to not just come and speak to the Commonwealth Club, but also make the case to the American public and the American Congress that these investments are in furtherance of our security, values, and interests, and that we’re going to be good stewards of those tax dollars.

So we are looking to — through the QDDR, the Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review that we’ll be rolling out before the end of the year, we are looking to start in motion reforms in how we do this business that will actually give us more impact for what we do and become very good stewards of the tax dollars that are provided to us.

QUESTION: Can you change the org chart? I mean, a lot of that — people talk about across agency collaboration, but until you’ve changed the reporting structure, what is it really going to change?

SECRETARY CLINTON: Well, I’ll give you one example. One of my priorities and the President’s priorities was to figure out how to rationalize and better coordinate what we did to end hunger and promote food security. So starting right after I got there, I asked my Chief of Staff, Cheryl Mills, to run a government-wide process, which meant bringing the Department of Agriculture in. It meant bringing the Millennium Challenge Corporation in. It meant bringing other agencies that have contact with people in. And we came up with a program we’re calling Feed the Future. And it was hard. I’m not going to sit here and say it was easily done. It was quite challenging to get everybody in the same room talking about their contribution and how we could better focus what we were doing to deliver results.

But at the end of the process, we came out with a program that is going to focus on improving agriculture so that people can become more self-sufficient themselves. USAID, the State Department, Department of Agriculture and then other agencies, we are working in a collaborative action. In fact, that’s where I met Raj Shah, because he was in the Department of Agriculture and was there designated person to come to these meetings. So we are working very hard now.

Bureaucracy is a challenge no matter where you find it. And we are conscious of that and you can’t just turn some key and change things overnight. But we have emphasized our Feed the Future Initiative, we’ve emphasized better organizing global health because we have USAID, we have the State Department, we have Health and Human Services, we have the Centers for Disease Control, we have PEPFAR, we have all these other groups that are working on this. And then we have a third whole-of-government initiative on climate change.

So we want to try to change the way our own government functions and then change the way other governments function and then deliver services in ways that make sense to people within their own cultural and political atmosphere.

QUESTION: Our guest today at Commonwealth Club of California is Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton. I’m Greg Dalton. We have — Afghanistan is a place where the U.S. is trying to promote economic development and democracy. And we have a question from the audience about how do you define success in Afghanistan?

SECRETARY CLINTON: Well, I define it as a stable country that is able to defend itself and is making progress toward institutionalizing democracy and better services for the people. In order to get to that, we have to work with the Afghan Government to build up their own security forces and we’re seeing progress in that arena. Not enough, but enough to be able to say we can see a path forward. We have to help rid certain strongholds of Taliban insurgency from interfering with and preventing the gradual expansion of security and stability. We have to really help the government at all levels understand how better to function and we have some effective ministries and others that have a long way to go.

So it is a multi-pronged approach that is both, from our perspective military and civilian. When I became Secretary of State, both our military and our civilian efforts were woefully under-resourced. We were basically treading water. And you either had to make a decision that the President was facing to try to move toward what I’ve just said is a model that I believe represents success, or not and just try to pick off insurgents and leave it at that. It is a very difficult environment for all the obvious reasons that this audience knows because you follow the news. But is not a hopeless one, and it is not a failing environment. It is one that has a lot of challenges that are inherited, that are inherent, that have to be dealt with.

It is not — its culture is not our culture. And the way that we have tried to approach the civilian side of the equation is to, number one, increase our presence. Upon reviewing where we were, we had fewer than 300 civilians and most of them were not in the country more than six months at a time. Very difficult to build relationships, to mentor, to do the kind of outreach we were seeking. We’re now over a thousand and they are full-time very committed experts from the agriculture experts to the education and health and rule of law and everybody else.

So it’s been an effort. I’m not going to sit here and tell you that I know what the end of the story will be, but I think that we have made a very effective commitment and we have an increasingly effective strategy that we are going to follow through on.

[…]

QUESTION: Let’s talk about Pakistan. A nuclear armed country, obviously, very important strategically to the U.S. And then all of the sudden, these floods which displaced 20 million people. Does that put Pakistan as a potential failed state or certainly complicate the process or make the country, the regime more vulnerable because now they have all these displaced people they have to deal with?

SECRETARY CLINTON: Well, it certainly makes a complicated situation even more so. It doesn’t make it a failed state. Pakistan has strong — some strong state institutions and some very strong cultural ties. The military is obviously the strongest, best functioning institution in the country and we have worked hard to support the democratically elected government, but we’ve been very frank with them about what they needed to do to become an effective government. And as you saw in the aftermaths of the floods — the civilian government was very slow to respond — the military responded as they had after the earthquake of ’05 and the United States was very much involved in trying to help that relief and recovery effort.

What has happened with the flood has set back Pakistan’s development. The last time I was there in July, I announced as part of a multi-year package of aid to Pakistan some infrastructure projects focusing on water and electricity that were very needed. Now, following the flood, the infrastructure needs are even more pressing — bridges that have been washed out, agricultural land that has been eroded, other kinds of systems like dams that were providing electricity either damaged or destroyed. So we’re taking a hard look and next week we will have another meeting of our Strategic Dialogue with the civilian and military leadership with whom we work and we’re looking at how we can better target it.

But I have also been really clear with this message to Pakistan. In Pakistan as well as outside of Pakistan, the United States cannot and should not be expected to help Pakistan with its development needs unless Pakistanis do more to help themselves, and that includes reforming a tax system that does not tax the elite and the landed propertied class. Pakistan has one of the lowest tax per GDP percentages at 9 percent in the world. And so we are working with them no reforming their tax system, because some of the richest people in Pakistan pay less than $100 in all taxes. And when I was in London — no, where was I — Brussels yesterday — (laughter) — I was with Cathy Ashton who is the newly appointed High Representative of the European Union and we did a press conference about aid for Pakistan. And I said and she certainly echoed our expectation that the elite of Pakistan do more to help their own country if they expect us to help them.

[…]

QUESTION: Another international issue that you signed in on last year was the Alberta Clipper, a pipeline from Alberta that brings tar sands, oil sands directly into Wisconsin to the U.S. Midwest. This is some of the dirtiest fuel in the world. And how can the U.S. be saying climate change is a priority when we’re mainlining some of the dirtiest fuel that exists. (Applause.)

SECRETARY CLINTON: Well, there hasn’t been a final decision made. It is —

QUESTION: Are you willing to reconsider it?

SECRETARY CLINTON: Probably not. (Laughter.) And we — but we haven’t finish all of the analysis. So as I say, we’ve not yet signed off on it. But we are inclined to do so and we are for several reasons — going back to one of your original questions — we’re either going to be dependent on dirty oil from the Gulf or dirty oil from Canada. And until we can get our act together as a country and figure out that clean, renewable energy is in both our economic interests and the interests of our planet — (applause) — I mean, I don’t think it will come as a surprise to anyone how deeply disappointed the President and I are about our inability to get the kind of legislation through the Senate that the United States was seeking.

Now, that hasn’t stopped what we’re doing. We have moved a lot on the regulatory front through the EPA here at home and we have been working with a number of countries on adaptation and mitigation measures. But obviously, it was one of the highest priorities of the Administration for us to enshrine in legislation President Obama’s commitment to reducing our emissions. So we do have a lot that still must be done. And it is a hard balancing act. It’s a very hard balancing act. But it is also, for me, energy security requires that I look at all of the factors that we have to consider while we try to expedite as much as we can America’s move toward clean, renewable energy. And the double disappointment is that despite China’s resistance to transparency and how difficult it was for President Obama and I to drive even the Copenhagen Agreement that we finally got by crashing a meeting of China and India and Brazil and South Africa, which —

QUESTION: I would have liked to have seen that one.

SECRETARY CLINTON: Yeah, that was — (applause) — well, we — so we got the Copenhagen Agreement and China did sign up for it. But at the same time, they’re making enormous investments in clean energy technology. And if we permit that to happen, shame on us. And it is something that — (applause) — United States should be the leader in. It is one of the ways to stimulate and grow our economy — (applause) — and create good jobs. So that’s just a small window into the dilemma that we’re confronted with.

[…]

QUESTION: You’re in the position, potentially, to think about future generations. I am 10-years-old and I’m worried about my future environment. What can people do to help. This is Ellie from a fifth grade. P.S. I’m here with my teachers. (Laughter.)

SECRETARY CLINTON: Hi, Ellie. (Applause.) Well, Ellie, I think that there is a lot that you can do, because it’s been my experience that young people are much more environmentally conscious and committed to protecting the world you’re growing up in than some of us older people are. And therefore, I think, working on projects in your school, asking questions like this of people like me who talk about priorities for our country. I think it’s important to work with the environment that is right in your area and there are lots of ways and lots of projects that young people are doing that set an example for what can be accomplished. And I’m out of politics, as you all know.

The Secretary of State is not involved in any political activity, and certainly not elections. So speaking as a private citizen — (laughter) — (applause) — I think people running for office should be asked to explain their positions on what they’re going to do — (applause) — and I know that from what I read in the newspapers these days, there’s a lot of frustration and anxiety and even anger in our country right now over unemployment, over feeling that our government is not working, our economy is not working, just a lot of concern, which is very real. And I hope that people take some of that energy and focus it on the environment and on climate change, because we really do have to have a longer-range view of what’s going to make our country strong and rich and — (applause) — smart and I have no doubt that the United States — and I obviously believe that President Obama’s policies are going to be borne out and demonstrate their effectiveness. (Applause.)

We didn’t get into the problems we’re in today overnight. We got into them over time. And we can get out of them, but we can’t get out of them if we’re not thinking, if all we’re doing is reacting and being upset and mad and looking for somebody to blame instead of really working together. And that’s going to require a renewal of American partnership and spirit about solving the problems that we face and not pretending that they are either ignored or resolved in any easy way.

So I’m hoping that your question, Ellie, will be on the minds of everybody. Because clearly the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat is all connected to our environment. And it’s up to us to give it to you in as good a shape as it should be. (Applause.)

QUESTION: Our thanks to Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton for her comments here today. And to everyone at the Commonwealth Club, thank you all for coming. Thank you for coming. Hope you’ll come and see us again.

SECRETARY CLINTON: Thank you, Greg.

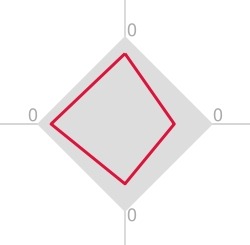

QUODA’s Quality of Aid Diamond tool enables users to quickly compare countries and agencies across all four dimensions. The figure to the left demonstrates that the U.S. rates below the mean in all four dimensions, when compared to all other countries.

QUODA’s Quality of Aid Diamond tool enables users to quickly compare countries and agencies across all four dimensions. The figure to the left demonstrates that the U.S. rates below the mean in all four dimensions, when compared to all other countries.