By Debika Goswami, Senior Program Lead, S M Sehgal Foundation

Farmer in his millet farm in Nuh, Haryana, India. Photo: S M Sehgal Foundation

In the culinary history of India, the existence of millets, also known as nutri-cereals, can be traced back to 4500 BC, which indicates it was an integral part of local food cultures for centuries. However, millet varieties were referred to as coarse grains in the post-Green Revolution phase in the later twentieth century. They were rapidly replaced by their more-refined counterparts, wheat and paddy, as significant staples in the agricultural landscape of India. With the marginalization of millets as a staple on consumers’ plates, its cultivation also became less cash remunerative. Hence, millet’s share in the total grain production of India gradually decreased from 40 to about 20 percent.

Despite the dwindling statistics, the importance of millet continues and is increasing with time due to its climate-resilient nature and highly nutritive value. Millets, being highly nutritious and resilient crops, offer a range of benefits that contribute to multiple SDGs. By promoting millet cultivation, we can address several goals, including zero hunger (SDG 2), good health and well-being (SDG 3), sustainable agriculture (SDG 12), and climate action (SDG 13). Globally, the consumption of millet is also gaining popularity due to its gluten-free nature. Rich in nutrients like iron, calcium, fiber, and protein and low in glycemic index, millets are considered a “smart food,”[1] beneficial for consumers and farmers (SDG3). They can survive less rain in higher temperatures and even saline soils. Millets, which can be used as food, fodder, and biofuels, have low cultivation costs and short crop cycles, making it well-suited for regions facing water scarcity or drought conditions cycles. Hence, numerous efforts were seen at the national and state levels to revive millet cultivation. Encouraging the consumption of millet-based products can contribute to improving public health and achieving food security. By promoting millet production, we can reduce pressure on water resources and enhance water efficiency, thereby supporting the sustainable use of water (SDG 6) and ensuring climate-resilient agriculture (SDG 13).

To promote the cultivation of millets as resilient, affordable, and nutritious cereals globally in the public psyche, the United Nations General Assembly declared 2023 as the International Year of Millets (IYM 2023). In India, millets were already rebranded as nutri-cereals in pre-COVID times (2018), followed by the emergence of several state millet missions in states like Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Assam, among others, to popularise millet cultivation among farmers. The Government of India is spearheading the celebrations of IYM 2023 by promoting it as a “people’s movement” and attempting to establish India as the global hub for millet.

To motivate farmers to adopt sustainable practices of millet cultivation and restore the presence of millets to the plates of consumers, the Department of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare has planned several millet-centric activities. These include food festivals/millet melas (fairs), training of farmers, awareness campaigns and workshops, and motivating Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) to showcase the diversity of Indian millets, among others.

Complementing rigorous efforts of the government to popularize Indian millets nationally and globally, a host of civil society organizations have adopted the promotion of sustainable millet cultivation among farmers. The primary objective is to motivate farmers to adopt millet cultivation and generate awareness about the rising global importance of millet as a prosperous and healthy cereal. Many organizations work closely with FPOs and various state millet missions to increase millet land acres, promote post-harvest processing enterprises, facilitate farmers to sell millets at minimum support prices (MSPs), and improve local consumption to address food and nutrition sufficiency.

Farmer in his millet farm in Nuh, Haryana, India. Photo: S M Sehgal Foundation

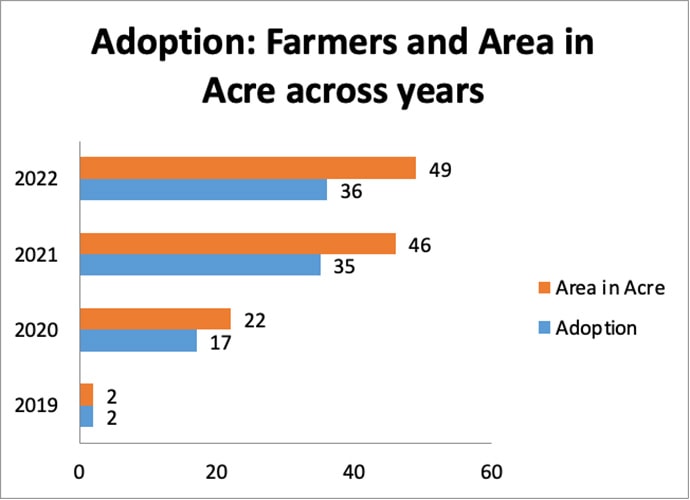

S M Sehgal Foundation promotes sustainable practices of pearl millet cultivation in multiple states, including Haryana and Rajasthan.[2] Farmers are encouraged to use recommended quantity of macro and micronutrients based on an initial soil test analysis. The balanced use of soil nutrients increases soil fertility and improves the quality and quantity of yields. Besides, farmers are motivated to adopt millet cultivation by replacing crops like cotton that could be more water-efficient. They are further encouraged to sell millets by registering under the government’s Mera Fasal Mera Byora[3] portal. Since 2020 with these efforts, more than 3,500 farmers have been motivated to start growing pearl millet on 3200 acres of farmlands approximately.

Story of Change

Before 2019, in Runera village, located 32 km away from the district headquarters of Nuh, in Haryana, farmers grew water-intensive crops like cotton, paddy, and pigeon pea as primary kharif crops, using water from a neighborhood canal. The aspirational district of Nuh, as enlisted by Niti Ayog, has semi-arid climatic conditions with an average annual rainfall of 336 mm to 440 mm and saline groundwater.

Sehgal Foundation (SF), under a CSR-supported partnership, started motivating farmers in Runera, who were completely unaware of the multiple benefits of millet cultivation, to adopt sustainable agricultural practices.

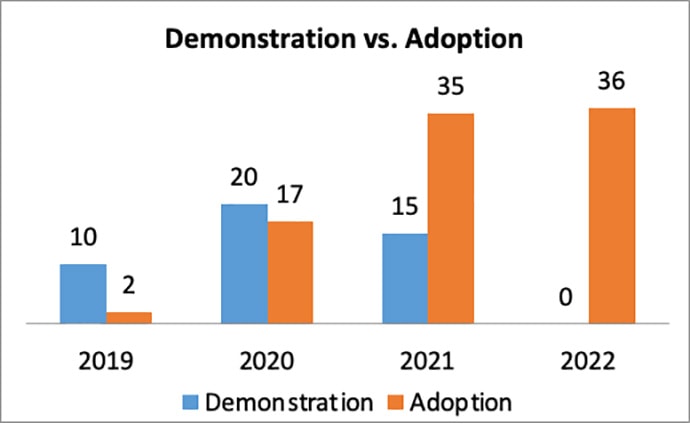

As part of this initiative, millets were reintroduced to the farmers as a climate-resilient and highly nutritious alternative to crops like cotton and pigeon pea. The team conducted multiple sessions with farmers and motivated them to cultivate pearl millet, emphasizing its growing global and national market demand. In the beginning, only ten farmers of Runera started pearl millet cultivation. These farmers were provided with a package of practices (PoP) for half an acre demonstrations including micronutrients such as zinc sulphate, boron, ferrous sulphate, potassium, and magnesium. The seed was provided for one acre. In the remaining half an acre, the farmers followed traditional cultivation practices of unabated use of Urea and DAP. Observing the success of millet cultivation in 2019, there has been an increase in the adoption of the micronutrient package of practice in three consecutive years, as shown in the graphical representation below.

In 2022, without any demonstration, millet cultivation was adopted by thirty-six farmers, which is about 20 percent of the entire farm area in Runera.

In terms of yield difference, the half-acre demonstration plots experienced a maximum of 480, 560, and 720 kilograms in 2019, 2020, and 2021 respectively, whereas in the same half-acre control plots, the maximum yields recorded were 380, 460, and 430 kilograms respectively (Average yield increases amounted to 23%, 25% and 31% in 2019, 2020, and 2021 respectively.)

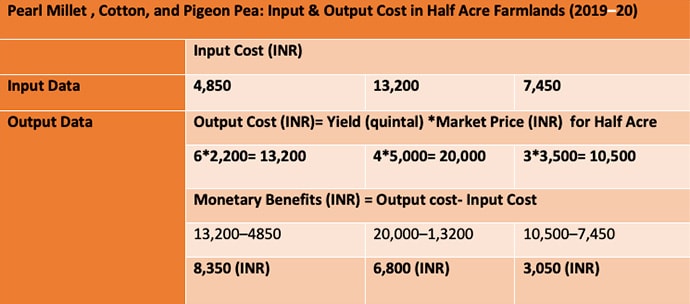

The once-forgotten and forbidden grain is creating new opportunities and silently changing the agriculture landscape in one of the remotely located villages of the Nuh district. The increase in adoption increased the area under pearl millet cultivation and replaced cotton and pigeon pea. Longer crop cycles (8–9 months) of cotton and pigeon pea incur greater costs in labor, pesticide, and irrigation cycles. Contrarily, millets require lesser inputs with shorter crop cycle (3–4 months) and are mostly rain-fed. In addition, cotton and pigeon pea are more prone to disease and weed infestation, negatively impacting the outputs and incurring losses for the farmers. The following table shows the cost of cultivation of each crop.

In villages like Runera, millets have the potential to offer smart solutions to address local issues of malnutrition among women and children, and the requirement of cattle feed.

Rizwana, a women farmer beneficiary, reports, “Intake of millets, which increased after we started growing them in our farmlands, improved digestion and controlled diabetes levels.”

The story of Runera aligns with what the FAO Director-General QU Dongyu mentioned in the Opening Ceremony of the IYM in December 2022: “Millets can play an important role and contribute to our collective efforts to empower smallholder farmers, achieve sustainable development, eliminate hunger, adapt to climate change, promote biodiversity, and transform agri-food systems,”[4]

[1] See https://www.icrisat.org/millets-are-good-for-us-good-for-the-planet-and-good-for-the-farmer-too/.

[2] S M Sehgal Foundation has been working since 1999 to improve the quality of life of the rural communities in India.

[3] The portal provides relevant information to farmers about crops, farming, availability, troubleshooting, and solutions through a one-stop online platform.

[4] See https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/international-year-of-millets-unleashing-the-potential-of-millets-for-the-well-being-of-people-and-the-environment/en.