Welcome to the April 2020 issue of the Global Washington newsletter.

IN THIS ISSUE

- Letter from our Executive Director

- Issue Brief: Amid a Global Pandemic, Implementing and Monitoring Sustainable WASH Solutions

- Organization Profile: Taking a Page From Global Businesses, Splash Finds a Way to Ensure Kids Get Clean Water and Lessons in Good Hygiene

- Goalmaker: Om Prasad Gautam, Senior WASH Manager at WaterAid

- Welcome New Members

- GlobalWA Member Events

- Career Center

- GlobalWA Events

Letter from our Executive Director

Right now, all of us are grappling with new challenges and strong emotions as we seek clarity and ways to push forward. Our routines have been upended, systems we depend on have been stretched to their limits, and we wonder whether we will ever get back to normal.

This new coronavirus has flipped the global development community on its head. Usually, we are the ones responding to emergencies in the Global South from a position of abundance, with the intellectual and financial resources from the U.S. Instead, several non-profit and for-profit organizations in the GlobalWA community are in need of urgent support ourselves.

In response, Global Washington will continue to bring you information and insights on how to strengthen your work and connect to one another. Check out our COVID-19 resources page for more and be sure to keep an eye out for upcoming virtual webinars, such as contingency planning and the CARES Act. GlobalWA will also promote the work of our members who are responding to the pandemic.

As with many contagious diseases, good hygiene is of the utmost importance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet many people around the world do not have reliable access to clean water. This month, GlobalWA is spotlighting organizations that focus exclusively on ensuring that communities in the Global South have clean water to drink and use every day.

In the newsletter below, you’ll read about our April Goalmaker , Om Prasad Gautam, a senior WASH manager at WaterAid and an expert in behavior change. You will also learn how our member Splash took a page from multinational corporations’ playbook to bring clean water to kids in urban centers, and then partnered with data visualization experts at Tableau to map the progress, showing governments how they can do the same.

We are committed to creating community for the global development sector and we are here for you. If there are other resources or webinars you would like to see, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

All my best,

Kristen Dailey

Executive Director

Issue Brief

Amid a Global Pandemic, Implementing and Monitoring Sustainable WASH Solutions

Photo by Water1st International at Hassan Al Banna Academy in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

By Joanne Lu

It’s been a long time since those of us in the West have been so acutely aware of our need for clean water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH). Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, health officials are constantly reminding us to wash our hands – and to do it right, with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, scrubbing between our fingers and under our nails. That’s the best way to remove viral particles from our hands to keep them from transmitting the virus to ourselves and others, they say. But for 2.2 billion people in resource-strapped contexts – whether refugee camps, urban slums or remote rural areas – access to clean water is still an issue, making the prospect of hand-washing several times a day much harder.

Some countries and organizations have stepped up with innovative immediate solutions. In West Africa, for example, some countries have reinstituted the public handwashing stations they used during the Ebola outbreak, consisting of two buckets – one with a spigot and filled with chlorine and water; the other one placed underneath the spigot to catch wastewater. More than a dozen countries have also submitted requests for a device that PATH developed that makes chlorine out of just water, salt and a car battery.

Immediate access is what matters most in the current crisis, but access to WASH services is of utmost importance even when we’re not facing a global pandemic. It improves every aspect of a community’s well-being – their health, income, education, safety, women’s empowerment – and can prevent future disease outbreaks. But just installing WASH facilities is not enough, otherwise we’d probably be close to achieving “clean water and sanitation for all” (Sustainable Development Goal 6) already. Instead, what researchers, sector leaders and organizations are recognizing is that robust data tracking and transparency is critical for ensuring that WASH projects are successful, sustainable and inclusive.

We’ve discussed before how as many as 30 to 50 percent of WASH projects fail after just two to five years, usually because of lack of maintenance, a broken part that can’t be replaced locally, or because the solution just wasn’t practical in the local context. Water1st was founded for this very reason – because too many WASH projects fail. Instead, Water1st decided that rigorous monitoring and evaluation, including lots of field visits, had to be baked into their organizational DNA to ensure that their projects would remain functional, now and over the long-term. They’re also constantly checking whether their projects are not only producing the intended benefits, but in fact the best possible outcomes. This means that Water1st’s projects, including piped water systems with a kitchen tap and shower for each household, toilets and hygiene education, are not the cheapest up front, but they are often solutions last.

“A robust and regular monitoring system [ensures] issues are addressed early rather than towards the end of a project,” World Vision says of their own approach to WASH interventions, because corrections can only be made if we understand when and why projects fail. That’s why World Vision works closely with communities and stakeholders to track, document and respond to “every change throughout a project cycle,” good and bad. The data are then measured against standard global indicators to evaluate each project. And the evidence and lessons learned are preserved and shared to help World Vision and others improve moving forward.

Data are not only critical for fixing faulty WASH systems, but also for better planning and decision-making to achieve SDG 6. Such planning creates a clearer picture of just how much more needs to be invested in urban and rural WASH systems. Data visualization through platforms like Tableau helps organizations like Splash literally see on a map where there are gaps in WASH service provision and how much they need to scale up year on year in order to reach their goals. Sometimes data reveal that the gap is not a lack of facilities, but of usage. That’s how Splash determined that behavioral nudges were needed – like mirrors above school handwashing stations that entice kids to spend time at the sinks, washing their hands while checking themselves out.

But organizations like WaterAid have learned that not all data are equal. In order to be truly useful, data must be accurate, timely, and as complete as possible. When WaterAid switched from organizing its data in Excel spreadsheets to a mobile online platform called mWater in 2014, the organization was able to streamline its efforts in data collection, reduce errors and inconsistencies (like double-counting and incorrect spellings of names for communities and institutions), build a large multi-year database, and conduct much more meaningful analyses. Data also could be disaggregated by gender, location, donor, partners, projects or funding, and their partners in the field could monitor and track progress at the community, sub-district and district levels.

Open and mobile data also empowers citizens to obtain the WASH services they need. In Zimbabwe, for example, UNICEF helped the government implement a real-time monitoring system. Instead of waiting for government field monitors to make their rounds before a deficiency is reported, people in rural communities can now just send an SMS directly to the government whenever a WASH service needs to be fixed. (Similarly, companies and organizations are stepping up with mobile reporting platforms for COVID-19 to help trace where the virus is spreading, so we can better contain it.) When organizations improve data tracking and analysis now, they can pass those tools along to governments and help ensure success in the long-run, when those governments take over responsibility for large-scale WASH services.

When large amounts of data can be used and shared in meaningful ways, it also holds providers accountable. Data transparency not only ensures that reported results are real, but it also builds trust from donors, whose contributions are critical for achieving clean water and sanitation for all. As Water 1st puts it: “We follow up. We routinely visit our projects to evaluate our work, to hold our partners accountable, and to share and exchange knowledge. We make sure each project is providing the intended benefits and generating the best possible outcomes. You can be confident that your donation is spent wisely and is making a real difference in the lives of the people we serve.”

Data tracking and transparency can seem like a risky proposition if it means being open and honest about failures. But it is also absolutely critical if we want to ensure that every person, household and community has access to the WASH services they need – especially in times like these, when proper hygiene is the best way to stop a global pandemic.

***

The following GlobalWA members are working to provide clean water to vulnerable communities around the world:

Agros

Agros International’s mission is to break the cycle of poverty and create paths to prosperity for farming families in rural Latin America. Founded in 1984, Agros advances a holistic socioeconomic development model of economic and social development through four key opportunity areas: land ownership, market-led agriculture, financial empowerment, and health & well-being. Its model recognizes the importance of water as an essential element of personal, public, and environmental health. Agros collaborates with government offices and other NGOs in rural areas and trains community leaders amongst the families it serves in order to create WASH initiatives, protect water resources, and implement environmentally friendly irrigation programs. Agros focuses on a landscape approach that includes reforesting campaigns and water management protocols to secure long-term availability of clean water. To date, 100% of the families living in an Agros village have access to clean water, basic sanitation services, and preventive health education. Additionally, families are learning to use environmentally friendly farming techniques and equipment to reduce water usage, securing its availability for future generations.

Friendly Water for the World

Founded in 2010, Friendly Water for the World is a dynamic, rapidly growing, 501(c)(3) non-profit organization based in Olympia, WA. Its mission is to expand global access to low-cost clean water technologies and information about health and sanitation through knowledge-sharing, training, applied research, community-building, peacemaking, and efforts at sustainability. The organization empowers communities abroad to take care of their own clean water needs, even as it empowers people in the U.S. to make a real difference. Friendly Water for the World currently works in 15 countries, and has assisted more than 190 marginalized and oppressed rural communities – including widows with HIV, people with albinism, survivors of war-time rape, victims of domestic violence and sexual assault, indigenous tribes, and unemployed youth – ensure their own safe drinking water while becoming employed in the process.

Hands for Peacemaking Foundation

Many villages that populate the mountainous areas of NW Guatemala are continually faced with a daily struggle to obtain water for survival. Since most village locations were based on available land, and not by the availability of natural resources, they often lack basic water resources. Many water sources have dried up due to the over-harvesting of trees to be used for firewood – an example of the domino effect that one resource has on another. Hands for Peacemaking Foundation (HFPF) has partnered with villages to install water storage tanks. These simple but effective means to collect water during the rainy season are coupled with water filters to meet the basic needs. The resulting water system doesn’t replace a well or spring, but it does provide emergency water that can mean life or death for villagers. HFPF has included the introduction of forest management in its training and education of villages after the installation of catchment systems. To date, the organization has installed 459 water catchment systems and 327 water filters in 19 villages.

The Hunger Project

The Hunger Project’s holistic approach in Africa, South Asia and Latin America empowers women and men living in rural villages to become the agents of their own development and sustainably overcome hunger and poverty. Through its WASH programs, The Hunger Project empowers rural communities to ensure they have access to clean water and improved sanitation, the capacity to develop new water sources, and the information to implement water conservation techniques. Since 2011, nearly 871,000 people have participated in The Hunger Project’s WASH skill or awareness building activities and the organization has trained over 20,000 local leaders in building community skills and awareness around water and sanitation.

Mercy Corps

Mercy Corps helps people around the world get clean water by providing water during emergencies, building wells to reduce long treks (often made by vulnerable girls and women), repairing damaged water infrastructure and helping construct reservoirs to ensure communities have access to clean water in the future. In Zimbabwe, Mercy Corps restored a community’s water infrastructure to provide clean and safe water for over 43,000 people. In turn, this also significantly reduced the distance girls had to travel to collect drinking water for their families. During emergencies, access to clean water plays a vital role in preventing disease outbreaks and other water-borne illnesses. In response to the ongoing humanitarian crisis in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where three quarters of the population lack access to clean water, Mercy Corps has provided over 600,000 displaced people with safe drinking water to help keep their families healthy and prevent disease. In 2018, Mercy Corps connected more than 3 million people to clean water and hygiene and sanitation facilities during emergencies across the globe.

Path from Poverty

In Kenya, with unclean water sources often miles from villages, woman and girls are forced to spend hours each day simply finding and transporting water. It is not safe for women and girls to fetch water in the very early hours of the morning. The daily average for a Kenya woman is 4-6 hours of walking for clean water. The typical container used for water collection in Africa, the jerry can, weighs over 40 pounds when it’s completely full. With much of one’s day already consumed by meeting basic needs, there isn’t time for much else. The hours lost to gathering water are often the difference between the time to do a trade and earn a living and not. Path From Poverty works to end this daily hardship and is putting a stop to girls lives being at risk by providing clean, safe water at the homes of women and their families. Empowering women, teaching them to work together, start a micro enterprise, and pool resources, Path From Poverty is changing lives and giving back the time lost fetching water so girls can go to school, women can earn much-needed income, and they can be safe from rape and abduction.

Splash

Splash is a nonprofit organization that designs child-focused water, sanitation, hygiene (WASH), and menstrual health solutions with governments in some of the world’s biggest, low-resource cities. Through Project WISE (WASH-in-Schools for Everyone), Splash aims to reach every school in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Kolkata, India, with WASH infrastructure, behavior change programs, and strengthened menstrual health services, benefiting one million children by 2023. Splash’s approach to WASH includes high-quality water filtration systems, durable drinking and hand washing stations, improved toilets, teacher training, and hygiene education to ensure that kids learn healthy habits. Their focus on hygiene, through handwashing with soap, is critical to stopping the spread of disease. To date, Splash has completed over 2,000 projects at child-serving institutions, including schools, hospitals, shelters and orphanages. Splash has reached nearly 600,000 children in eight countries (China, Cambodia, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, India, Nepal, Thailand, and Vietnam).

Water1st International

Water1st is unwavering in its commitment to projects that provide households, schools, clinics and community centers with enough water to drink, cook, wash hands, flush toilets, bathe, clean clothes, wash dishes, and sanitize household surfaces. There has never been a better time to justify an investment in high-quality infrastructure for clean water and toilets for the world’s most vulnerable people. The return on this investment will impact us all for generations to come. Water1st’s country programs in Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Honduras are busy at work, building new water systems and providing outreach to communities about how to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus. In Ethiopia and Honduras, the 2020 goal of Water1st is to connect 675 more households to piped water systems. In Bangladesh, the organization is providing support to 35,000 people, building new water systems and providing support to households to prevent the spread of coronavirus. More information about Water1st’s COVID-19 response can be found here.

WaterAid

WaterAid is working to make clean water, decent toilets and good hygiene normal for everyone, everywhere within a generation. As the leading international clean water nonprofit, WaterAid works in 28 countries to change the lives of the poorest and most marginalized people. In the face of the COVID-19 threat, WaterAid is scaling its efforts to improve handwashing and hygiene education in every country where it works. Since 1981, WaterAid has reached 26.4 million people with clean water and 26.3 million people with decent toilets.

World Vision

World Vision (WV) believes that every child deserves clean water. WV is focused with partners on providing children, their families, and communities with quality, sustainable access to safe water, sanitation, and hygiene services. In the last 4 years, WV reached 16.1 million people with clean water because of a unique community engagement model and global footprint. In response to COVID-19, WV is scaling up its water and health efforts in 17 initial priority countries, aiming to reach 22.6 million people, half of them children, over the next 6 months with protective and hygiene items. This includes scaling up hand washing stations in health clinics and working with more than 250,000 community health workers to help reach communities to teach critical behaviors to prevent the spread of infectious disease. In 2019 alone, WV reached 4.3 million people with hand washing behavior change education and facilitated the building of nearly half a million hand washing facilities. WV is concerned that the COVID-19 outbreak could disproportionately affect women and girls. This is one of the reasons WV is focused on equipping and empowering women and girls in every aspect of our work so they can reach their full potential.

Organization Profile

Taking a Page From Global Businesses, Splash Finds a Way to Ensure Kids Get Clean Water and Lessons in Good Hygiene

By Joanne Lu

Photo courtesy of Splash.

What do Big Macs, orphanages and clean water have in common? More than you’d think, it turns out.

In 2003, Eric Stowe was working in orphanages in China and around the world, when he decided to ask the caregivers and administrators, “What can I do for a child living in an institution that would have both an immediate and long-term health impact?” He got a lot of answers, but the two most consistent ones were better training for caregivers and clean water. In institutions where three children are sharing a crib and 150 kids are living together, a case of diarrhea spreads like wildfire without clean water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH). Stowe had no idea how to train caregivers, but providing clean water seemed “totally approachable and achievable.” After all, it made no sense to him that just down the road from these orphanages, the hotel where he was staying had clean water, as did McDonald’s, Starbucks and Burger King.

So, he decided to just ask those companies: How do you do it? How do sustainable filtration and maintenance systems service so many people? Those conversations led to a partnership around 2004 with Antunes, the company that supplies all the water filtration systems for McDonald’s globally. These systems are built for very high-volume food service and produce high quality water with very low technical service. “Today, if you went into any orphanage in China and went into their kitchen, you’d find the exact same filtration system that you’d find in McDonald’s,” says Stowe, “and it’s still working 12 years later, maintained once a year for about five minutes.”

Stowe’s mission to provide clean water to every orphanage in China was the early genesis of what would later evolve into Splash – but you’d hardly know it given the approach and scale of Splash today. Stowe started Splash in 2007 with the idea that in any one city where there’s a single orphanage, there are potentially hundreds of other institutions that regularly interact with the poorest urban kids. Why only focus on orphanages? Starting with orphanages and hospitals in China, Cambodia, Nepal and Ethiopia, Splash later expanded to feeding centers, street shelters and rescue homes – and eventually schools – in eight countries.

But then they began to hone in on how they can be really excellent, instead of just good. Without abandoning existing projects, Splash is now focusing its growth on just two cities: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; and Kolkata, India. The organization’s goal is to reach 100 percent of the schools in those cities – about 1 million kids – by 2023.

Photo courtesy of Splash.

“Everywhere we work, nestled in the greatest pockets of poverty are schools,” says Stowe. Through these schools, Splash helps kids adopt practices every day that keep them safer and healthier. Often, the kids take those practices home and teach their parents, and one day, they’ll likely teach their own kids.

What started off as just a mission to provide clean drinking water quickly is now, by necessity, a package of services that also includes handwashing education, safe sanitation, and menstrual hygiene. Key to Splash’s approach is “human-centered design.” For example, handwashing stations, which are always orange, and drinking water stations, which are always blue, are kept separate to reduce the risk of water re-contamination. The handwashing stations are also too shallow for kids to stick their heads under the tap for a drink, and bubblers (water fountain spouts) are always on the right side of a drink station, because kids traditionally wipe their bums with their left hands. Additionally, Splash found that by simply installing $5 mirrors near the handwashing stations, there was a double-digit increase in users – primarily by girls pretending to be interviewed and boys checking out their fledgling moustaches!

Splash also works with teachers, parents, janitors and student groups to reinforce their messaging throughout the day. Stowe talks about how one little girl, who was appointed the “Minister of Health” for her school, pulled a boy out of the lunch line because he didn’t wash his hands first.

All those interventions and programming occur at one school. It’s complex when it’s just one school, Stowe says, but it’s downright unwieldy when you’re trying to do 100 percent coverage of all the schools in Addis and Kolkata. Splash began its drive in these two cities last year, but the longer-term goal is to use the success of Addis Ababa and Kolkata to show governments how they themselves can replicate the same model in other cities. But, in order to do that, Splash needs to be able to literally show government partners how it’s done.

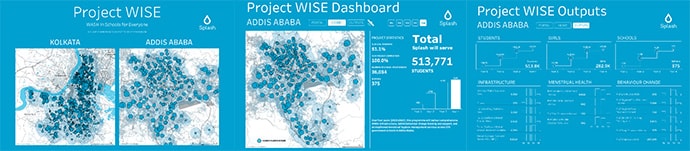

Enter Tableau. Stowe says that when he told the interactive data visualization software company about his vision, the people at Tableau told him, “Listen, this is a really big, audacious project. If your goal is for replication, you’re going to have to prove out a lot of things, and you’re going to have to make the data navigable.” And Tableau was up for the challenge. So far, the company has committed about 1 million dollars to the project, including a five-year grant for $750,000 ($150,000/year), Tableau software licenses, training, and support from their Zen Masters, a group of experts who are nominated by the Tableau community and to share knowledge and provide guidance.

Photo courtesy of Splash.

Splash has been committed to data transparency from its inception, but it lacked the tools to use its data in a meaningful way. Stowe says that prior to the partnership with Tableau, Splash didn’t have a single map that could show every single plotted school where they work. They have that now – an interactive map that shows Splash’s footprints across Addis Ababa and Kolkata and how many kids are being reached by each of those footprints. They can also see exactly how much they need to grow over the next five years in order to reach 100 percent coverage.

In time, Splash and Tableau hope to be able to show not just outputs but outcomes – to see not just where Splash has implemented programs, but how those areas have changed as a result of the programs. The Tableau dashboards will also eventually be able to help with project workflows and planning and, of course, make it easier to share all this data with governments so they can see for themselves what’s working and what’s not. “This is huge,” says Stowe. “My ability to tell the government what we’re doing is exponentially easier through [Tableau] than through any kind of spreadsheet or conversation.”

Screenshots of Tableau dashboard created using data from Splash projects. View larger image.

For now, Splash is focused on getting all the Tableau tools they need for Addis Ababa and Kolkata up and running, but eventually, they also hope the platform will capture their past successes – like getting into every orphanage in China across 1,100 cities – and failures as well.

“Absolutely, seeing the amount of work ahead can feel overwhelming,” says Stowe, “but to me there’s nothing negative about that. It should be nerve-wracking, like any meaningful work is.”

The added challenge right now is how to stay on track amid the COVID-19 pandemic, which has shut down schools in both cities indefinitely. However, Stowe says there is a positive: “There’s going to be an entirely new and dynamic conversation around handwashing that we’ve not been able to do on our own before. I think you’re going to see kids washing their hands far more, and that is a really good thing.”

Goalmaker

Om Prasad Gautam, Senior WASH Manager at WaterAid

By Penny Carothers

Dr. Om Prasad Gautam was a handwashing champion before any of us had heard of the novel coronavirus and COVID-19. And while he’s pleased to see governments everywhere encouraging handwashing as a primary defense against the disease, he doesn’t believe that what you could call the coronavirus effect will increase handwashing worldwide once the crisis is over.

That’s because Dr. Om has seen and studied disease outbreaks and the role of handwashing. At first, there is an uptick in handwashing, but inevitably that upward trend plummets once the threat retreats. Understanding this phenomenon is central to his work on behavior change. Knowledge and fear, though heady motivators in the face of a pandemic, do not lead to the kind of long-term behavioral change we need to combat the next pandemic, not to mention the everyday epidemic of diarrheal diseases in low- and middle-income countries.

This problem—how to get people to make positive changes in their lives that become sustainable, or habit—is a primary focus of Dr. Om’s research and life’s work. Before the specter of coronavirus exposed our vulnerabilities, he had been working to crack the code on behavior change, specifically with hygiene. The consequences of a lack of clean water and sanitation are well-known, but Gautam wants to shift that perspective slightly, because studies show that it’s not just a lack of water and sanitation, or taps and toilets, that cause disease. It’s a lack of hygiene practice.

“In water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), without behavior change the services we offer are not going to be used or sustained. Handwashing with soap can reduce diarrheal diseases by 48%, but the problem is that only 19% of people actually wash their hands and 60% of households globally have handwashing facilities. We’re not finding the right motivation for people to change their behavior.”

For the past five years Dr. Om has led WaterAid’s behavior change and global hygiene programming as WaterAid’s Senior WASH Manager. WaterAid is “determined to make clean water, reliable toilets and good hygiene, handwashing in particular, normal for everyone, everywhere within a generation.” To support this goal, Dr. Om’s day-to-day work includes both internal and external commitments. He supports country offices through coordination, capacity building, and global guidance, standards, and frameworks. He also represents WaterAid in academic, private, and sector partnerships and global forums. All of these relationships are essential to such a considerable goal.

Om drinking water from gravity flow system tap, supported by WaterAid, through a local partner, NEWAH, in Udayapur District in Nepal, July 2009.

Caption: Om drinking water from gravity flow system tap, supported by WaterAid, through a local partner, NEWAH, in Udayapur District in Nepal, July 2009.

When Gautam joined WaterAid, the 40-year-old organization was launching a new global strategy. “It was perfect timing for me to bring some of the transformative shifts to the organization,” he explains. “My goal is to make sure [WaterAid] country programs implement robust, effective, evidence-based behavior-change programming that results [in] sustained behavioral outcomes.”

From Health to WASH

Gautam started his career working on child health, food safety, immunization, and HIV/AIDS projects at the World Health Organization and with Nepal’s Ministry of Health. This focus shifted slightly while studying for his Masters of Public Health at BRAC University. After spending time in a local cholera hospital, where he was exposed to the destructive result of a lack of clean water and sanitation, he was moved to work in WASH. Gautam began working with WaterAid Nepal and in 2009 he responded to the largest cholera outbreak in Nepal’s history in the Jajarkot region, where 30,000 people were infected and hundreds died. Considered one of the fathers of modern epidemiology, Dr. John Snow tracked and helped put a stop to an outbreak of cholera in London in the 1840s. More than 150 years later, Om wondered why people were still dying from this preventable disease.

Two years later, Om followed that question to its logical conclusion, as a Ph.D. candidate at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. With many years of field experience, he was looking to study transformative interventions shown to have lasting and significant impact. “I like evidence,” Gautam says. “We need evidence. As human beings working in public health, in the WASH sector, in charity, we don’t have the luxury to waste time, to test the failure of programming all the time. If programs aren’t evidence-based, they’re not going to be long-lasting.”

Behavior-Centered Design

In working toward his Ph.D. and beyond, Dr. Om’s intention was to integrate science into development practice and to contribute to practice-informed science. He studied food safety and hygiene behavior change at the London School with Valerie Curtis, one of the pioneers of a school of thought called behavior-centered design.

Behavior-centered design takes the view that people know what’s good for them, they just don’t always do it—an assertion that anyone who has tried to follow through with a New Year’s resolution can probably relate to. Behavior-centered design builds on, as Curtis wrote in 2015, “a particular set of evolutionarily important tasks humans must solve in order to survive and reproduce” and satisfy needs. They follow basic principles related to motivation and habit creation, such as social conventions, cultural expectations, and geographical setting. Or, more simply, says Dr. Om, “Behavior change is all about changing the script in peoples’ heads through motivation.”

Dr. Om with a group of participants in a safe food hygiene trial.

Organizations that use the behavior change model, like WaterAid, focus on the ABCDE approach (Assess, Build, Create, Deliver, Evaluate), which identifies the levers (the social, physical, and biological factors) that change behavior, coupled with a design process to create, implement, and evaluate the program. This approach starts with listening to communities to identify universal behavioral determinants (such as disgust, love, or status) and design approaches that tap into these motives.

It doesn’t end there. Om insists that interventions must be coordinated and integrated into government plans as well as other ongoing development efforts (such as immunization campaigns, education, and nutrition). WaterAid and other organizations following this model are focusing on strengthening systems to sustain these services and behaviors so that programs are “layered and iterative,” leading to universal access.

Dr. Om points to a current WaterAid project in Nepal that integrates hygiene into an immunization program run by Nepal’s Ministry of Health. The pilot started in four districts serving 35,000 mothers and is now being scaled up nationwide to reach 650,000. WaterAid is running similar systems-level campaigns in 17 countries. Internally, the organization is building centers of excellence on behavior change, sharing lessons learned and best practices with a broader federation, and empowering country programs to share what is and is not working, all in an effort to build knowledge in the sector.

Dr. Om Prasad Gautam presenting at WaterAid’s February 2019 Global Hygiene Conference

Today, the novel coronavirus is the most urgent public health threat facing the countries where WaterAid works. The organization takes a “do no harm” approach, having stopped face-to-face interaction. Instead, WaterAid is working with partners on media campaigns and providing handwashing facilities. When it’s safe to do so, the organization will pivot to behavior change programming. If Dr. Om has anything to do with it, in the next epidemic that comes along, vastly more people globally will practice the life-saving habit of hand washing.

Welcome New Members

Please welcome our newest Global Washington members. Take a moment to familiarize yourself with their work and consider opportunities for support and collaboration!

SIGN Fracture Care International

SIGN is a humanitarian organization that builds sustainable orthopaedic capacity in developing countries by providing relevant education to surgeons, then manufacturing and donating the instruments and implants needed to treat fractures. Signfracture.org

Member Events

April 14: PATH: Real- Time Epidemic Response

April 16: World Affairs Council: Rethinking National Security in the Age of Pandemics

April 17- 24: FIUTS Blue Marble Bash

May 30: Global Visionaries: Virtual Auction & Gala

Career Center

Senior Development Manager (Individual Giving), The Max Foundation

Manager, Grants and Contracts, Village Reach

Information Systems Officer, Global Partnerships

Check out the GlobalWA Job Board for the latest openings.

GlobalWA Events

April 10: Contingency Planning for Fundraising

April 17: Overview of the CARES Act and Paycheck Protection Program (PPP)