Many people in global health talk about how Coca-Cola supply chain practices could be applied and adapted to health commodities to ensure that vaccines, malaria treatment, family planning commodities, and many more essential medicines are available at the last mile health facilities. And they have a point—I have seen Coca-Cola in pretty much every village I’ve been to in Africa throughout my almost 20 years of going to these remote places.

Many people in global health talk about how Coca-Cola supply chain practices could be applied and adapted to health commodities to ensure that vaccines, malaria treatment, family planning commodities, and many more essential medicines are available at the last mile health facilities. And they have a point—I have seen Coca-Cola in pretty much every village I’ve been to in Africa throughout my almost 20 years of going to these remote places.

However, that cannot be said for the south part of the Equateur Province in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

I’ve just returned from a two-week supply chain assessment in this province that is divided by the Congo River, and then is crossed and crossed, and crossed again by its many tributaries. Someone described it as the most isolated place—not just in the DRC but in all of Africa. And I believe him.

Our team literally “laying the groundwork” for us to continue down the main road

The health staff have to travel more than 40 kilometers or more (by bike, foot, motorcycle and/or by water via a canoe or barge) to go and pick up medicines from the health zone to replenish their stock. In many places the “main road” isn’t more than a narrow dirt path.

We hit a couple of rainstorms along the way; I can’t even imagine what that dirt path is like during the proper rainy season.

When the health workers finally arrive at their destination, in many cases, the health zone is out of stock, and they must make the same journey home- empty handed.

Getting vaccines to these areas presents even more challenges because of the cold chain needed to keep vaccines cold. Without electricity, the cold chain equipment at the reference hospital or health zone should run on either solar or petrol.

Most of the refrigerators that we saw had not been working for at least a year.

The narrow dirt path that serves as the main road

Most of the refrigerators that we saw had not been working for at least a year. So health workers make do the best they can.

In one health zone, which holds the vaccines for more than 20 health centers, they use the electricity from the communications tower across the street to freeze ice blocks to keep their non-functioning solar fridge cold. Health workers will go once a week to the health zone to pick up vaccines using a cold box in order to facilitate a once-a-week vaccination day for children.

For some health workers, this is just a couple of kilometers down that dirt road; for others, it could be up to a 40, 50 or 80 kilometer trip to go and fetch vaccines.

One of the many non-working fridges we encountered

For some health workers, this is just a couple of kilometers down that dirt road; for others, it could be up to a 40, 50 or 80 kilometer trip to go and fetch vaccines. Again, the transportation methods vary – sometimes by bike, by motorcycle, by a two-day walk, by water, or a combination thereof. The commitment to their community and to children’s health is commendable.

Yet, despite these valiant efforts, the inability of the system to reach its most vulnerable is undeniable, and has a serious human cost- as underscored by the recent New York Times article on a deadly measles outbreak in the DRC.

A health worker walks across the street to access a working refrigerator to refreeze ice packs

For me, this has been a reality check. At VillageReach, we “start at the last mile.” I have been reminded how ‘last mile’ some places really are. You may not be able to get a Coke, but hopefully, with changes to the supply chain, you will be able to get vaccines.

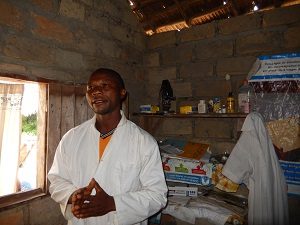

A health worker in Lolanga Zone

See more amazing photos from the journey here →

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

As Program Manager, Wendy Prosser is responsible for the design, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation of health system programs for VillageReach in Mozambique. Efforts in Mozambique seek to streamline vaccine logistics with an improved logistics management information system and transport services.

As Program Manager, Wendy Prosser is responsible for the design, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation of health system programs for VillageReach in Mozambique. Efforts in Mozambique seek to streamline vaccine logistics with an improved logistics management information system and transport services.

Wendy has over a decade of global health experience in program development and management, research and analysis, capacity building, and behavior change communications. This experience has taken her to Mozambique, Malawi, Angola, Kenya, and South Africa in various public health settings, starting with Peace Corps in Cape Verde. Wendy holds a MPA in International Development and Global Health from the University of Washington.