By Joel Meyers

Dr. Kingsley Ndoh

Thank you, Dr. Ndoh, for joining us today!

Thank you so much for having me really, really a pleasure and an honor.

It is our pleasure and honor for sure. Please tell us a little bit about your background, and what drove you to work in the field of oncology.

I’m originally from Nigeria. I moved to the US 13 years ago and I remember when I was coming here, I actually thought I was coming to Washington DC, I didn’t know that there were 2 Washingtons (laughter). I went to medical school in Nigeria, and just when I graduated, my very close aunt unfortunately passed on from colorectal cancer. She had had abdominal symptoms that were misdiagnosed for a year before it was caught, and unfortunately it was late stage.

So at that time I started thinking, “how can this be solved?” Because I realized that it was just not her, but it was an example of a bigger problem.

That was one of my motivations of coming to the US – to study more and to train. I ended up at the University of Washington doing a master’s in public health, with a concentration in global health. After that, I joined Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center as a fellow, then I joined the Global Oncology Program there and at the time the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center had recently started the global oncology program. They’re one of the pioneers.

And that’s what set me off in my career trajectory.

And you are also an affiliate professor at the Department of Global Health at UW.

Yes. My primary position right now is the CEO of Hurone AI, yet I have an affiliate faculty position at the Department of Global Health, and I’m also an affiliate faculty member at Fred Hutch.

Amazing, and I’m excited to talk about Hurone AI, your company, yet I wanted to first ask about how you were introduced to AI? And why did you choose to focus on AI?

That’s a very good question. I was on a plane traveling to Europe. I think I was traveling to Africa at the time. This was in 2017, and usually when I’m flying, I like to read. And there was I was reading called Humans Need Not Apply by Jerry Kaplan.

In that book Kaplan talked about the different applications of AI in different industries, and how things were growing in AI, especially in machine learning, the neural networks. They were talking about different industries, including healthcare. One of the things mentioned in the book was that healthcare is the slowest adopter. For obvious reasons. Patient data is very sensitive.

But the paradox there was healthcare had the highest amount of data in any sector in the world, and unfortunately it was lagging significantly behind in AI innovation. This got me thinking around how we can use these technologies to transform oncology and cancer care. I was thinking more about cancer, because that was the area I’ve been working in. I thought about things like, how do you, in a situation where you have fewer oncologists say in Africa or in rural America, how do you deploy these technologies to augment these people? How do you use these technologies to argument radiology, for example, when you have one radiologist for several people? How do you use that as a tool to argument and make that oncologist a superpower? That’s when AI caught my attention. No one was really talking about it, as you know, like what we have today.

The explosion of generative AI, and AI in general, has seen over 40 years of research and applications. It’s just that now it has come to the fore, and it has now been mainly democratized. That’s really what got me thinking about applying artificial intelligence in cancer care.

When you realize this about AI, how did you start integrating it into your work?

So, I wouldn’t say I integrated it in my practice, or any of that. I was thinking more about how to build an organization around it, build a solution, find out the pain points, and see what we can tackle with this technology.

After talking to a lot of oncologists, one thing was very clear, they were overburdened. They needed tools that could pull different sources of data to provide them with treatment protocol suggestions. Patients needed more connections with the healthcare system.

To build this kind of technology, the entrepreneur in me (and the other part of me is that I’ve always been an entrepreneur) was thinking about how to build a company to test this technology and build a product, because you have to have a product – a working product – to actually build a company. I knew that I couldn’t simply build a product and start using it in the clinic. There’s regulation and there is the amount of investment that needs to go into it. That was how I started ideating, and essentially to build any product, you have to talk to the potential end users – in this case, doctors and patients – as well as looking at how it’s going to work within a healthcare system. And talking to the different stakeholders in artificial intelligence in general, to learn more because my background is not in computer science.

So that was what I was doing over those early years – just learning. Then I eventually launched the startup company in early 2022. We started testing in Africa in Rwanda before we eventually came to the US.

This is actually a great segue to Hurone AI, your company. It sounds really interesting.

Hurone, the word, without the “e” means a ferret, like a weasel, in Spanish. And the ferret usually is variegated in color. It’s white, black, and brown and is used for medical research. So to us, diversity in data can lead us to precision medicine. So in that vein at Hurone we are building what we’ll say is the oncologist’s best buddy. Think about this co-pilot as a digital oncologist that collaborates with oncologists to ensure that it provides the best personalized care for patients and their families using the power of artificial intelligence.

So it analyzes the personal records of that patient…

Yes, it starts pulling out salient, specific data points.

Mainly, it is a clinical decision support tool. There are two things that it does.

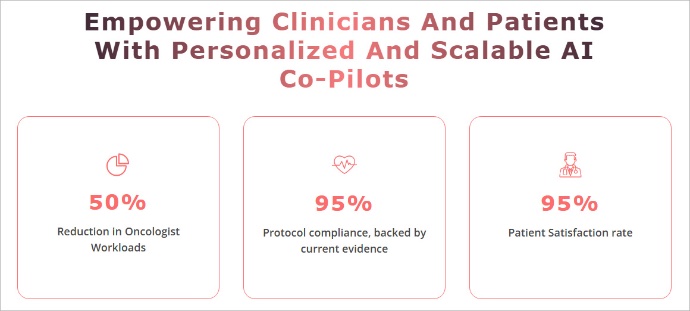

Firstly, it automates a lot of processes like referrals – automates a lot of the workflows. In terms of the automation of workflows, it decreased the time that oncologists will typically spend on these tasks by at least 50%.

The second thing is retrieving patient data and matching it to the relevant guidelines, including their comorbidity. For example, someone that has a cancer diagnosis may have other conditions; the person may also be diabetic, so you have to treat the person holistically. When this patient has received a diagnosis of cancer, and they are diabetic, merging the latest guidelines in real time, including relevant research, with that patient data to produce treatment options for the patients with pros and cons and the rationale, all the doctor needs to do is to look at it and discuss it. And they can check the references if they want to, and it can also serve as a collaborator in multi-disciplinary tumor boards [of experts].

We’ve made things very easy for them. They are not missing any particular updates in the guidelines. Because guideline updates happen quite frequently, and many doctors can’t keep up, there’s typically a time lag between what they do for their patients and what is currently available.

In the US, you can see how valuable that would be for value-based care systems where we’re moving from a fee for service to a closer focus on the outcomes. Are you complying with the latest guidelines for this patient? This is the kind of value we are bringing using artificial intelligence.

Screenshot from the Hurone AI website.

This sounds amazing, and I imagine you’ve thought of additional applications of Hurone AI to be able to consolidate records and automate a lot of the back-office tasks, especially for community health workers out in the field. I know that that is a constant challenge.

Yes, absolutely. Whether you’re looking at the US healthcare system, or in Africa, there are “navigators” that help patients navigate the complexities of the healthcare system when they have cancer. So if you think about a patient receiving a diagnosis of cancer, the first things they want to understand are what that diagnosis is about, what is their journey going to be like, what is remission in this treatment I’m taking, and what kind of side effects am I going to get? So with the co-pilot, for the patient, it simplifies all that. They can interact and ask questions, and that reduces time for the community health workers or the navigators who usually have to spend an additional hour explaining all this to the patient…and it’s just information overload.

Patients need more help navigating very complex healthcare systems, especially when there’s a cancer diagnosis. The system becomes much more complex because that patient is dealing with several multidisciplinary teams where they have several appointments plus imaging appointments. You know they have to deal with insurance. Probably by the time the patient is done with treatment they get a PhD. in insurance and knowing what claims are covered!

Doctor and patient. Photo: Fernando Zhiminaicela/Pixabay

So all these challenges we want to simplify as much as we can. Right now, where we’re providing value as we speak, is our oncology copilot, the treatment copilot for clinicians. Because there’s a huge disparity when you look at the outcomes in community cancer centers versus academic cancer centers in the US. In Africa, when you look at the number of deviations that oncologists often deal with because they have a lot of patients to see, they need something that will just make it easy for them to provide the right treatment.

It sounds like, through the application in Africa and the US, you’re learning different things, and the knowledge gained is feeding each other to create a better product or a better process with the copilot AI.

Absolutely. Right now, our focus as a company has been on coming to oncology centers in the US even though we started in Africa. But one of the key agreements we have in Kenya is not just using the system there but also learning and using their data to train or to fine tune our system. And it’s very, very valuable here in the US because there are several studies that show that the genetic diversity of Africa is the highest in the world, and you tend to get even certain cancers that are more prevalent in Africa.

If you look at breast cancer, the cancer tends to be more aggressive that we’ll find in the US, and sometimes what we see there is similar to black populations here, and so there are so many things we can learn from an AI point of view, because it runs with data, as you can imagine, to improve healthcare systems. And that’s really global health, right? Global health is closing disparities internationally and also at home.

Oh, that’s fascinating… I was looking at your UW profile, and I saw a Lancet Oncology Commission on cancer in sub-Saharan Africa study you participated in. What was that, and what were some of the significant outcomes?

That was some of the work that I did with other commissioners. The big gap that the Lancet wanted to address was that we don’t have comprehensive data on cancer in Africa in general, from treatment to the epidemiology. They brought together experts to look at everything, the whole continuum, from prevention down to treatment and funding, so that we have a comprehensive study out there that other people can build on, whether it’s companies or other researchers who want to use the data. The research is a very, very comprehensive report that detailed the landscape of cancer in Africa and made recommendations, and one of the recommendations in that report was the critical use of technologies like AI in closing some of the gaps. It’s a very, very important report, and highly cited because a lot of people are building on it. To make any change, you have to have baseline data. And that’s what that report is all about.

Was that before Hurone AI – did that help motivate you to create Hurone?

That was before Hurone. Yes. And yes, we refer to a lot of the data there, especially when we did our pilots. And that’s what research does, right? With these kinds of research, you have data out there that a lot of people can use to solve problems. But when the data is not there, you don’t know where to start from. You don’t know what the problems are to probe. And that’s why global health research is really important.

And I would imagine – and I experienced this a little bit in my past job trying to pull all kinds of data sets from different countries – that everybody has their own rules and reporting structures and methodologies. So I would imagine, with the models that you’re creating with Hurone, the intake of data has got to be fairly flexible.

Yes, it’s not easy for sure. Number one, you have to find where the data is more structured, and then two, you have to go through the regulations, you know, ethics regulations to use that data, and if possible, even get secondary consent. And so there are lots of steps, and it could be expensive, but it’s worth it. Because if you don’t have representative data in the things you’re doing, then you introduce things like bias and building models that are not contextual to the populations that you’re serving.

Right. That makes a lot of sense. Do you go back to Africa often?

Yes, I do, especially to Kenya, because we have an active program going on there. The last time I was there was late last year, and I’ll definitely be going there again, although we have boots on the ground managing the project there.

In Africa, when talking to clinicians and other doctors, what do you see as an area where there could be the largest impact AI in healthcare?

First and foremost, in general for healthcare, the biggest impacts would be seen in automating a lot of the things that doctors do in general, because they are overwhelmed. In Africa, the patient ratio is as much as 1 to 6,000 per doctor, per capita. That’s very high. In the US I think it’s 1 to 500, or less. The WHO recommends 1 to 250.

If you think about talking to a patient and having that conversation automatically transcribed, and you are reviewing the patient and want to develop a treatment plan, you can have AI help you at least bring options to the fore that you can consider which would greatly reduce medical errors, elevate the quality of care, and streamline workflows for doctors.

One of the things that people are afraid of, which it does to an extent, is the replacement of jobs or the reconfiguration of certain jobs here in the US.

Clinicians in a hospital lab. Photo: Samuel Gabriel/ Pixabay

In Africa, you need more doctors, and so you need AI to really augment the people that are there working. Obviously, there are challenges in terms of the need to have functional electronic medical records. Some hospitals are still paper-based. The paper-based ones do have an opportunity to leapfrog and use AI co-pilots to do the work, which can serve as your electronic medical record service.

The other thing is funding. These technologies are not cheap. In a budget constrained environment, you have to develop very innovative business models that will make it attractive to make it work.

What do you think is the biggest barrier to AI adoption? There is it the cost…

Yes, the budget is one of the biggest barriers. The other is the workflow infrastructure. I know that’s kind of vague, but what I mean by workflow infrastructure is how can you fine tune workflow with your own patient data. Has that data been stored over time in the cloud, or is it one that is inconsistent?

Funding is really paramount, because at the end of the day you have a situation where these technologies are not free, they have to be reimbursed one way or the other, and so you have to deal with the existing business systems. There’s insurance, but if there’s insurance, are you demonstrating an ROI to that insurance, because it’s there to improve patient outcomes.

If it’s government funded, those governments might have constrained budgets, and you have to show those governments that if you invest X amount of money in AI or other technologies, that would save you Y amount of money, which sometimes is difficult to convince a government of that. And working within the right business systems that already exist, figuring out how to work in places where maybe 20% of the population is covered by insurance – figuring out that whole, and especially with the funding landscape (you know now you can’t depend on a USAID, for example, to fund it), African governments and healthcare leaders really have to think about innovative business models.

There are cheaper contextual AI models that can be built and used in Africa. We demonstrated this already with our work in Rwanda and even Kenya. But you have to really be innovative on how to structure a business model that includes AI implementation, which is not something that can easily be funded. Yes, philanthropic funding can come in, but these are not sustainable. You have to really figure out sustainable ways to sustain it, and then you can bring in other funding partners as complementary. But there must be core sustained funding. Otherwise in the next five years we’ll be talking about talking about the disparities in AI, like “this is what AI is doing” and “how can we do it in Africa”? So this has to happen, and there has to be political will to say that we need to figure this out.

This is where we can have more outsized returns than even the global north because there are fewer regulations in Africa, which is good and bad, so you can implement things faster.

Obviously, we have to protect the patient. Think about digital (virtual) doctors in a rural area that has never seen a doctor, or even the people that provide care there for just the outpatient clinic such as community health workers, and error rates can be as high as 60-70%, but common – just ChatGPT alone can improve these outcomes.

There was a study that was published late last year in JAMA, where ChatGPT versus a human internal medicine doctor, ChatGPT was better in the US. Yes, ChatGPT versus an internal medicine doctor, ChatGPT alone was better.

Wow…

Right? So if you think about just those results, you can implement real quick things that will be quick wins. Thinking about it, we have over three billion people in the world that would never see a doctor. And this is where the case for at least a digital doctor that assesses malaria patients can justify AI use. And a place like Africa has the opportunity to really accelerate that AI implementation.

And I would imagine there would be a real fiscal argument for funding AI because in the long run it’s going to save money in healthcare costs, government costs, in healthcare population costs… there are so many deeper ripple effects with improved health care.

Yes, and I hope other governments will be reading this. There is the need for more doctors – how are you going to recruit or get those physicians? You have to train them, and that’s millions and millions of dollars, and many years at least for just a doctor to graduate, then more years for residency and fellowship. There needs to be that investment. And that’s not even a guarantee that that doctor is going to remain in your country when you spend all that money – the person could end up in the United States.

How do you do a hybrid model where you’re going to invest in AI? Because AI in healthcare can easily help a lot of your population and it’s going to bring down healthcare costs, and if political capital is your incentive, that will give you a lot of political capital to win your next election. So in the end, yes, it’s the ROI – it can be calculated on pen and paper, but just thinking about it from a logical perspective, it’s very clear ROI.

Hmm, yes, it’s going to be very interesting to see how quickly AI infiltrates not only healthcare workforce augmentation, but so many other workforces in the years to come.

Do you see in Kenya, for example, people still holding AI at arm’s length because they’re still very hesitant about AI because they are not clear on the ethics and security of it?

Not so much in Kenya. Kenya is one country that is very innovative. I don’t know if you know of this technology called M-PESA? It was one of the first mobile monies in the world before PayPal. So that’s how very forward-thinking Kenya is, so they are very open to new technology.

There are other countries that are still skeptical. And then there is also the whole topic about data sovereignty. Some countries need certain data to remain in their country. And some of the major cloud providers in the world have to deal with this which can pose barriers in terms of how you can implement the cloud in general in these locations including for AI. But in general countries are receptive.

There was a study by PWC a few years ago, I think this was back in 2016 or 2017, where they asked, “would you be willing to see a digital doctor?” in India, South Africa, Nigeria, the Uk and the US. In India, South Africa, and Nigeria, over 80% of people were willing, and it makes sense right? Because at the time if I don’t have access to a doctor at the time I need it, and it’s a robot that’s going to see me? Why not?

That was then. Now I think those percentages will have changed in the US and the Uk, but in the US and the Uk, it was around 40% even though we have better access to doctors – I want to see my doctor, why would I go to a robot when I can more easily make an appointment and see my human doctor?

Now that I’m learning more about AI, and I’m using it more and more in my daily work, I see how it’s a game changer in so many ways.

Have you noted any areas of AI adoption that should be cautioned against or adopters taking special care to avoid?

Yes, three things.

First, it needs to be easily explainable and be evidence-based. In healthcare specifically, in implementing any AI solution especially when it comes to clinical decisions and navigating patient conversations and needs, all that should be easily explainable. There’s even a field called “explainable AI.” So what I mean by that is, when you have an output, it should give some explanation to why? Doctors think about evidence, and not simply accepting what you give me, so it has to be contextual.

Clinicians discussing patient diagnostics. Photo: Accuray/Unsplash

Second, it needs to be contextual. For example, if a 28 year old male comes to a Seattle clinic and says, “I have a fever, I have some night sweats,” one of the things the doctor is going to be thinking about will be Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which is a type of cancer. But in Kenya, a doctor is going to be thinking about malaria. So if you’re designing an algorithm for clinical decision, and it’s fine-tuned to this environment with the epidemiology and all that, you’re going to be misdiagnosing, or that’s not going to come up as a top differential diagnosis in a place like Kenya. So it needs to be contextual. And that’s why, looking at fine tuning with the population, their data is really important, so that you don’t introduce biases that might not really fit that population.

And third, it should be very easy to use. It can’t be another burden to the physician or healthcare worker. For example, if you add new additional steps and tasks you are adding to their already taxing work. One has to figure out how to really integrate it into workflows so that it’s not an additional burden to an already overburdened healthcare worker.

These are some great insights, thank you.

You’ve answered this next question somewhat already, but I’m going to ask it a little bit more directly: when thinking about the use of AI in international settings, especially low- to middle-income countries, what advantages and biggest gains do you see now or anticipate?

There are two things. AI will incredibly reduce the disparities in treatment outcomes and in access – the quality of care and the access to care. I believe AI will be a huge game changer in reducing these disparities. Then we can start seeing a more balanced, equitable world.

This is the first time, I think, in our lifetime that we have the opportunity to have a technology that can really move the needle, or that can shift the needle in a very significant way.

Are you seeing a lot more teladoc use? Automated telehealth, that’s AI driven?

Yes. There is definitely a lot of effort right now in low- and middle-income countries for just video conferencing. But you also have to think about the context again. Data might be prohibitively expensive, not everyone might be using a smartphone. So there’s also text-based consultations where parts of it are AI driven. These kinds of uses are definitely growing and becoming more mainstream.

But like I said, the key thing is building local contextualized solutions, because a lot of solutions might not be exportable to certain populations. It will serve a percentage of patients, but it could create another set of disparities.

Ah, another great point and caution.

Do you have any final words you’d like to share with our global development community?

Yes – a reminder that global health starts locally. One of the major problems UNAI is solving is our disparity here in the US, where we see a huge disparity between treatment outcomes in community cancer centers where 1.4 million Americans go to academic cancer centers. And then internationally, this is the most important time in global health where we can truly make a huge difference by implementing AI-based solutions.

I’m very happy to see that a lot of organizations are already keen on seeing how we can leverage many, many years of effort and shorten it using AI to see some huge and significant change in terms of access to health and closing treatment disparities.

Thank you again so much, Dr. Ndoh, for taking time today. It’s a great comfort knowing that Hurone AI is out there, and that you’re doing this hard work. And your words are so important. And they reflect almost exactly what I’ve heard from other experts around AI. I am really excited to be able to report this out for our global health communities who may be hesitant about AI adoption.

Thank you. I really appreciate you taking your time. And I’m looking forward to continuing the conversations.

Here, I think you meant my clinical practice? I wasn’t prating, I was doing more of cancer research, but the answer seems as though, I was practicing. Could you please make this clear of rephrase the question to ….how are you integrating AI in your work?

It can also serve as a collaborator in multi disciplinary tumor boards.