By Amber Cortes

A health care worker explains to a patient how to self-inject Sayana Press, the DMPA-SC self-injectable contraceptive, at the Dominique Health Center in Pikine, Senegal. Photo: PATH/Gabe Bienczycki

Rachel Ndirangu knows her numbers.

“Nearly 300,000 women die annually from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth, with 95% in LMICs,” says Rachel, the Africa Regional Director for Advocacy and Public Policy at PATH, an organization that works in countries around the world to advance health equity and close the gender health gap.

For Rachel, these aren’t just statistics—it’s personal.

Rachel was born in the Rift Valley, Kenya “in one of the very lush, green tea plantation areas” where she grew up in a family of four siblings.

At the age of three, she lost her biological mother to eclampsia, a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy that causes seizures, and one of the main direct causes of maternal deaths in Africa.

As Rachel got older, she became curious about the health inequities and health system challenges that contributed to her mother’s death, particularly in her region of Sub-Saharan Africa.

“It gave me a chance to start thinking critically about, you know, why did that happen? Would it have been prevented? And appreciating that it didn’t just happen to me, this happens to hundreds of families daily,” says Rachel.

“And I think this spurred in me the need to work in the global health space. And particularly advocating for equitable access to essential health services for women and girls.”

Rachel Ndirangu, Project Director, Advocacy and Public Policy at PATH

Now a mother of three, Rachel continues to grow her passion to close the health equity gap for women and girls, particularly in her region.

Her role at PATH involves identifying solutions to address policy and financing barriers and accelerate improvement in core primary health care outcomes especially related to Maternal Newborn and Child Health and advancing global health research and development.

Rachel focuses on advocacy and public policy work in Africa. It’s rewarding, she says, to collaborate with diverse partners including policymakers, global health partners, local advocates, and communities to bring health within reach of everyone.

But finding support from public officials and policy makers is not without its challenges.

“Policy influencing is not as easy as just presenting data, or making a human rights argument or an economic argument,” says Rachel.

“Advocacy must be directed to the hearts and minds of these decision makers in order to inspire action.”

For Rachel, this means building relationships through inclusive and continuous dialogue, which takes investments of time and financial resources. Rachel sees every collaboration as an opportunity to build trust, and empower constituents with a sense of ownership and political will.

Using this philosophy, in a long process of addressing policy barriers impacting access to newborn and child health services, Rachel and her team were able to engage policymakers in Kenya around the need to come up with the first ever unified policy for Maternal Newborn and Child Health. This was further reinforced by the adoption of a comprehensive Primary health Care policy framework and Primary Care Networks implementation guidelines that are strengthening the delivery of integrated person center services and products for women, children, and wider communities.

Melanie Impanga Kalenga, a “Mentor Mother,” delivers a health talk to mothers at Kenya General Reference Hospital in Lubumbashi. Mentor mothers are HIV+ women who have successfully given birth to an HIV-negative child and now mentor other HIV+ women who are pregnant. Photo: PATH/Georgina Goodwin

A key highlight of PATH’s policy advocacy in 2023 Uganda is the adoption of the country’s updated and responsive Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child, Adolescent and Aging Health and Nutrition (RMNCAAH+N) strategic Plan, along with an Advocacy Toolkit to help strengthen accountability across all stakeholders. This policy document serves as an important tool for guiding prioritization, planning and resource mobilization for provision of essential health services and technologies as well as tracking of health outcomes for women, girls, and children in Uganda.

“So, it just shows the importance of having actions grounded in strong policies that then rally all actors towards a common action agenda,” says Rachel.

Rachel and her team in PATH have also played a critical role in helping countries understand, adopt, and ratify the African Medicines Agency (AMA) Treaty which aims to improve access to safe and effective medical products in Africa.

There is a need, Rachel says, to meet the challenges of building effective and efficient regulatory process for new products and pharmaceutical innovation that will increase equitable access to populations including women and girls.

According to Rachel, the health needs of women and girls, especially in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), are frequently overlooked, under-researched, and underfunded, leading to chronic underservice by health systems and limited access to comprehensive and affordable care. Regulatory inefficiencies further delay the introduction of essential health products, denying millions of women timely access to lifesaving technologies.

High-income countries dominate the health research and development (R&D) agenda, neglecting the unique needs of women in LMICs, resulting in inadequate products and services. This is exacerbated by insufficient inclusion of women in product design.

There’s also, Rachel says, a tendency to address women’s health in silos, such as a program that focuses exclusively on family planning while another focuses exclusively on HIV prevention for adolescent girls and young women, neglecting to address women’s health needs holistically.

Essential to meeting these challenges is PATH’s concept of self-care (hint: it’s not bath bombs).

“It’s really about enabling women’s access to interventions that place them at the center of their own health decisions,” says Rachel.

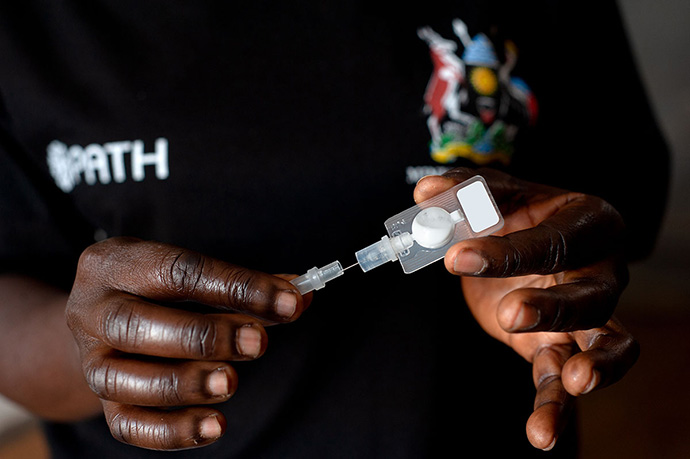

One example is the DMPA-SC injectable contraception, a an ‘all-in-one’ self-injectable contraceptive that protects against pregnancy for three months.

Such an intervention, Rachel says, has dual benefits, both to the individual by improving their health literacy, increasing their autonomy, and supporting them to participate directly in their health care, but also to the health system because it leads to more sustainable health systems by optimizing the time spent on patient interaction and reducing the burdens of health care providers.

A health worker with Mildmay Uganda leads a family planning information session for clients, demonstrating the self-injectable contraceptive, subcutaneous DMPA (DMPA-SC). Photo: PATH/Will Boase

This kind of self-care, says Rachel, really has the transformative potential to preserve women’s autonomy, their choice, and even access.

“It’s broken some of the barriers related to, like, I need permission from my husband to go to hospital, or I need to have resources to be able to even just get money or transport to the hospital,” says Rachel.

“So, putting that choice and decision-making power in the hands of women has been quite impactful. In 2023 alone, nearly 1 million DMPA-SC self-injection visits took place across 59 countries that have approved it.”

A community health worker in Uganda demonstrates the self-injectable contraception, subcutaneous DMPA (DMPA-SC). Photo: PATH/Will Boase

Another way to put the power of women’s health in their own hands is being sure women’s voices are included in the R&D process.

In 2023, with support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, an analysis was conducted by PATH on women’s inclusion in health R&D processes in Kenya and Nigeria, examining policies and assessing the implementation of laws promoting women’s health R&D.

Findings revealed a significant gap between policy and practice: only 25% of clinical trials in these countries exclusively addressed women’s health concerns. Cultural, social, and religious barriers contribute to limited participation in clinical trials and STEM education, resulting in products that inadequately address women’s needs.

The study suggested focusing on policy implementation, establishing funded programs for women’s healthcare careers, providing mentorship opportunities, and collaborating with women-led health advocacy organizations to advance inclusive R&D agendas for women.

Rachel says there’s only one way that global health organizations can focus on meeting the needs of women and girls.

“We need to harness the collective power of innovation, research, and advocacy to create a world where every woman and girl has access to the health care they deserve. But to do that, we need to put women at the center and always remember the investing in women’s health is investing in the global economy!”