September 2021 Newsletter

Welcome to the September 2021 issue of the Global Washington newsletter.

IN THIS ISSUE

- Letter from our Executive Director

- Issue Brief: Jobs Have Been Hit Hard By the Pandemic, Yet Some Orgs Are Learning How to Rebound Even Stronger

- Organization Profile: Spreeha – Organization Spotlight

- Goalmaker: New Mercy Corps CEO Takes the Helm as Covid-19 Makes the Organization’s Mission “More Urgent Than Ever”

- GlobalWA Member Events

- Career Center

- GlobalWA Events

Letter from our Executive Director

It’s hard to believe that it’s been nearly 19 months since many of us, who were fortunate enough to do so, started working from home due to Covid. Unfortunately, many people lost their source of income entirely as lockdowns shut down several service sector jobs. In low and middle income countries, those in the informal economy were hit the hardest and lacked access to government assistance. It’s estimated that in 2020, the global economic impact of Covid led to 97 million additional people in extreme poverty.

However, I am inspired by those in the Global Washington network who have adapted out of necessity and created profitable, resilient sources of income. It also reflects a process of rebuilding for equity that could be a model to replicate around the world. Below are articles focused on inclusive growth for the future. The organizations and people mentioned are great examples of this through the ways they are evolving and innovating, forging pathways to be even stronger and more adaptable.

The past 19 months will be remembered as a time of massive global disruption and upheaval. Yet, 2022 promises to be the year of rebuilding and reimagining new systems for a more equitable future. On December 8 and 9, Global Washington will convene our virtual 2021 Goalmakers Conference to chart a new course in the years to come. We have some amazing speakers lined up with many interactive sessions and breakouts. I hope you can join the conversation. More information can be found here.

Kristen Dailey

Executive Director

Issue Brief

Jobs Have Been Hit Hard By the Pandemic, Yet Some Orgs Are Learning How to Rebound Even Stronger

By Joanne Lu

A year and a half on from the World Health Organization’s official declaration of a global pandemic, the world is still learning how to adjust to our new reality. On many fronts, the pandemic has made it clear that the world we lived in before is not one we want to return to – without a robust response to health emergencies, without sufficient safety nets for marginalized communities, and without justice and equity.

Few understand the need for change more than the world’s most vulnerable and the organizations working to help them. Although the pandemic has been devastating for many organizations, there are many that have also taken the opportunity to evolve, become more resilient and build the resilience of the communities they work with.

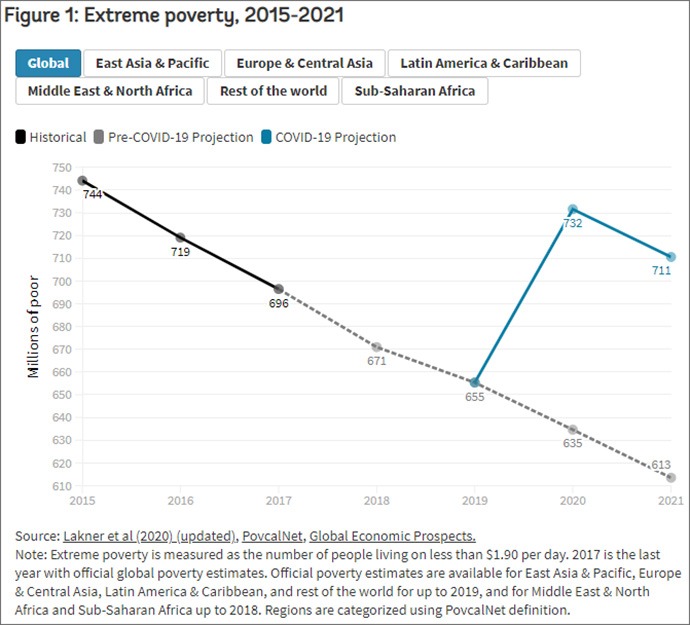

Still, it has been far from an easy task. The pandemic created in 2020 the deepest global recession since World War II, according to the International Monetary Fund. Unsurprisingly, the impact was greatest in the poorest areas of the world. By World Bank estimates, the pandemic led to 97 million more people being pushed into extreme poverty (measured as living on less than $1.90 a day) in 2020. It’s a devastating number, and it represents enormous shifts in livelihoods and pathways out of poverty for millions of families living in under-resourced areas.

Screenshot of World Bank blog.

The pandemic hit informal workers, who make up about 70 percent of the global workforce – particularly hard. These include household workers, street vendors, waste pickers and other daily wage earners. Lockdown measures not only put most of them out of work, but they were also mostly excluded from relief packages, like stimulus payments and unemployment insurance.

For organizations to adapt appropriately to the needs of the communities they serve, they must listen to their constituents and monitor the situation carefully. That’s why Global Partnerships (GP), an impact-first investment fund manager, has been diligent about staying in close communication with their social enterprise partners and the clients they serve. Through mobile-based surveying, end-clients have expressed reliance on savings as a coping strategy, but also a deterioration in their financial position and heightened food insecurity. This feedback reaffirmed GP’s commitment to supporting high-impact social enterprises that provide basic goods and services that foster economic resilience and enable people to earn a living and improve their lives.

In August, GP launched its ninth fund, the Global Partnerships Impact-First Growth Fund, LLC, which is designed to support high-impact social enterprises that are well-positioned to not only survive the pandemic but also grow and scale impact. As of its first close, the fund had $45.5 million committed, and it has the ability to scale to $100 million.

The decline in nutrition has prompted many other organizations to launch new relief initiatives. Spreeha Foundation and Spreeha Bangladesh, for example, works to help people break out of the cycle of poverty through health care, education, skills training and employment opportunities (note: Spreeha is not an investee of Global Partnerships). In the early days of their operations, Spreeha also provided one meal a day through their education program, but due to a dissipating need in the community, they ended that service. However, the pandemic reignited that need in an alarming way, prompting Spreeha to provide food and nutritional supplements.

Photo credit Spreeha. Pregnancy time counselling.

Another GlobalWA member, Awamaki, which provides opportunities for artisan weavers in Peru through sustainable tourism, had to make a sudden shift to food relief as well. This was a big change for Awamaki, which has always been focused on providing opportunities and training. But their model was upended overnight. With the help of small and large donors, Awamaki has been able to provide their partner artisans with monthly food baskets during this trying time.

Like many organizations, technology has also been critical to Awamaki’s adaptation during the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, they never designed goods for online sales. They didn’t have to, as their store in Ollantaytambo, near Cuzco, made about $80,000 a year from tourists. Without that store, they had to start selling online. They received a grant to specifically design products, particularly home goods, for online sales, and they also partnered with Amazon to host virtual shopping tours. Through a beta platform called Amazon Explore, shoppers can book virtual visits to their store.

Screenshot of Amamaki’s virtual store on Amazon.

Spreeha Foundation has also noticed local resilience. For example, even though Spreeha had to pause most of their vocational training programs because of lockdown measures, several women from their sewing training groups took the opportunity to launch their own sewing businesses during the pandemic. Others, particularly young people, have used the skills they gained through Spreeha’s training programs to move away from daily wage jobs to higher-skilled work, like cell-phone repair.

For organizations like these, the pandemic has been an opportunity to lean into the challenges and changes of these unprecedented times. The pandemic exposed many of the injustices that marginalized communities face. But it has also revealed what true resilience, sustainability and equity should look like. And perhaps, it’s given us a clearer roadmap for how to build back better.

The following Global Washington members are helping with job creation and economic development in low and middle income countries.

ACT for Congo supports humanitarian work without creating dependence. We work with organizations that are locally conceived, owned, and operated to help them build their capacity so that we become unnecessary for their success. Our role as outsiders is primarily to support locally-driven initiatives led by competent and wise leaders.

Over the past eight years we partnered with a Congolese start-up that built a vocational school now recognized as a Center of Excellence (HOLD-DRC). Our partnerships include Congo Nouveau, who provided civic education in 19 cities, and POLE Institute, who conducts vital socio-economic research in DR Congo. Our newest partnership is with AGIR-DRC who supports refugees in pathways out of internally displaced camps, provides clean water for children in schools, whose partners provide training and advocacy for domestic workers, and fuel urban gardeners and reforestation in Goma and eastern Congo.

Over 1400 women graduated from HOLD with state-issued certificates in vocations. More than 900 are employed or have their own business.

Awamaki teaches women’s artisan cooperatives in the rural Andes how to start and run their own businesses in sustainable tourism and fair trade crafts. Awamaki connects artisans to global markets and provides training in product development and business management. Their highly-skilled artisan partners create alpaca accessories, woven bags, and home goods, blending contemporary design with traditional techniques and motifs. Awamaki supports 180 artisans who are lifting their families towards prosperity.

Capria is a global venture capital firm with expertise investing in fintech, edtech, jobtech, logistics/mobility, agtech/food, and healthcare in the Global South. Capria invests in regional soonicorns — startups with enough revenues and growth rates to be unicorns soon — and also backs local and regional fund managers with capital and strategic support. Capria and its global network deliver profits with scaled impact aligned with United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Capria has offices in Seattle, Bangalore, Nairobi, Santiago and Washington D.C.

Chandler Foundation helps to build strong nations, vibrant and fair marketplaces, and flourishing communities. We imagine a world in which nations are well governed, principled businesses drive economic growth, and all people have the opportunity to flourish. Through patient, long-term, system-changing investments in trusted partners, we can help build thriving economies that work for everyone.

Because in a world where talent and creativity are unleashed, the impossible is possible.

More than 800 million people around the world live on less than $1.90 a day. Concern Worldwide believes that number can and should be zero. That’s why our mission is ending extreme poverty, whatever it takes. Our approach to ending extreme poverty is rooted in the understanding that the cycle of poverty is fueled by a combination of inequality, vulnerability, and risk. Our livelihoods programs address some of the underlying problems experienced by people trying to earn a living while also dealing with the challenges and setbacks of extreme poverty.

In 2020, we reached 4.4 million people through our livelihood programs. These programs aim to provide participants with the tools needed to ensure they are able to earn a sustainable living, learn new skills, improve the productivity and nutritional value of their crops and set up small businesses to generate more income. However, even with a job, 8% of the world’s workforce still live in extreme poverty, which is why we take a “targeted, time-bound, holistic, and sustainable” approach to breaking the cycle of poverty. For example, our Graduation Program uses a multi-pronged approach to giving families the education, training and funding they need to achieve financial independence. In other words, the program helps participants to “graduate” out of extreme poverty – once and for all.

Respect for the legal and customary rights of communities to land and natural resources is a principal objective of Earthworm Foundation’s work in global supply chains. We partner with companies making strong commitments to these rights, and then provide tools and practical training needed to see them realized. A central focus is helping ensure that land development for commodity production only occurs with the requisite Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) of local people.

Supporting the economy and resilience of smallholder farmers is at the heart of our work. We began our efforts to strengthen farmer resilience in 2011, and today we work with farmers in 15 countries. We promote crop and income diversification so that farmer households have more secure livelihoods. With strategies tailored to their needs, approximately 3,000 farmers have diversified activities and their average household income increased by 20%.

We also focus on promoting safe work environments and labor rights. In 2017, Earthworm launched a labor rights and workers’ welfare program, training thousands of workers in over 60 companies. Our projects promote the welfare of children in oil palm plantation regions, ethical recruitment of migrant workers, the rights of casual and temporary workforces, and improved wages for agricultural workers.

Heifer International believes ending global hunger and poverty begins with agriculture. Operating in 21 countries across Africa, Asia and the Americas, Heifer provides farmers with technical assistance and opportunities to strengthen essential skills, including finance and business management. Farmers receive expert support to improve the quality and quantity of the goods they produce, as well as connections to markets to increase sales. As Heifer works to build sustainable food systems, it engages women and youth across value chains, ensuring they have the knowledge and tools needed to increase their incomes and support their families. Recently, Heifer published “The Future of Africa’s Agriculture: An Assessment of the Role of Youth and Technology,” a report based on a survey of 11 African countries, that identified challenges preventing youth from fully engaging in farming as a source of future jobs. In response these issues, Heifer launched the AYuTe Challenge which awards up to US$1.5 million annually to the most promising young entrepreneurs who are using technology to reimagine farming and food production across Africa. For the 2021 competition, the AYuTe Challenge selected Cold Hubs and Hello Tractor as winners, supporting them as they scale their businesses to help more farmers to overcome long-standing challenges.

Mercy Corps works in over 40 countries helping communities forge new paths to prosperity in the face of disaster, poverty, and the impacts of climate change. Mercy Corps’ approach to protecting and strengthening economic opportunity ensures crisis-affected households can maintain their businesses and wage incomes in the midst of crisis, while laying the foundation for greater market participation and inclusive economic growth in the future. Throughout the pandemic, Mercy Corps has worked closely with people living in vulnerable areas to meet their most urgent needs by providing cash while also implementing long-term solutions to ensure businesses can recover and continue to provide employment opportunities.

In Jordan, Mercy Corps channeled 13,000 JD ($19K) in emergency cash to three gig platforms to help them continue to provide essential services to gig-workers and also provided 90 workers with a cash transfer of 150 JD ($210) each to meet immediate basic needs and selected three start-ups for further technical and funding support as they demonstrated high potential to recover and grow beyond COVID-19 and continue to employ hundreds of gig workers.

Microsoft – Building Skills for the digital economy

We’re living in a changed world. As economies continue to reopen, more jobs will require digital skills. This is not just about technical jobs, but an increasing number of jobs across industries that will become ‘tech-enabled.’ Now, and in the future, all people will need to learn digital skills to pursue in-demand roles, but access to the resources to learn these skills is inequitable.

Microsoft is focused on supporting those who have been excluded from opportunity because of race, gender, geography, displacement, or other barriers that prevent them from attaining the skills needed to thrive in a changing economy.

Our programs, partnerships, and resources are designed to meet people where they are on their skilling journey. From a young person learning computer science in the classroom, to a job seeker earning technical certifications, to employers focused on building skilled, inclusive workforces, we are committed to helping people gain the foundational, role-based, and technical skills to gain jobs and livelihoods.

To achieve this, we invest in supporting communities in building equity, building nonprofit capacity and scale, and mobilizing collective action, funding, and impact by working with others to advance sustainable, scalable change.

Learn what steps we’re taking and how you can help support: aka.ms/skills

At Opportunity International, we are proud and honored to be a part of achieving this first Sustainable Development Goal, along with many of the other SDGs that are focused on improving the standard of living for families in poverty. Together with organizations and initiatives around the world, we spend each day helping amazing people break that barrier of living on $1.90/day. And, in the wake of the pandemic, we are more committed to this goal more than ever.

We invest in entrepreneurs, helping them create or sustain jobs for themselves and their neighbors. Also, we have created tailored tools for farmers, addressing many of the challenges faced by the rural, agrarian majority of those living in extreme poverty. We work to connect them to markets, give them access to inputs, and help them move from subsistence to commercial agriculture – radically transforming their farms and their futures. We realize our goal is the same as that of the U.N. as we are actively working to end poverty in all its forms everywhere.

Opportunity International’s core programs continue to enhance and expand upon our continuous work on behalf of women and girls in low- and middle-income countries. We reach out to financially excluded populations, especially less literate and rural women, to deliver knowledge and skills that help them use financial services as fuel for their journey out of poverty. Financial services are key for women to create their own livelihoods, who are often excluded from formal economic opportunities. When women can create their own economic opportunities, they become powerful agents of change and some of our greatest weapons in ending extreme poverty.

Remote Energy

Remote Energy believes that access to reliable sources of sustainable energy is a fundamental requirement for the advancement of education, healthcare and quality of life. It is also a critical step in promoting sustained, inclusive, economic growth. As solar energy (PV) grows exponentially, so does the fast growing need for a trained solar workforce. Remote Energy has responded by developing and implementing regionally appropriate, customized technical capacity building programs and developing hands-on, practical learning opportunities for solar technicians and instructors in marginalized communities worldwide.

Remote Energy’s Native American Programs partner with tribal vocational and technical schools to provide scale able, accessible PV training opportunities for Native Americans in their own communities. Programs focus on the development of hands-on skills specifically designed to give aspiring instructors and technicians the marketable skills required for employment in the fast-growing PV industry and inspire communities to move towards energy independence and sustainable development.

Remote Energy is also committed to gender equality and support the belief that women’s talents and leadership are vital to maintain a diverse, sustainable, PV industry and critical in promoting economic grow. Remote Energy’s Women’s Program is designed to develop women decision-makers, end-users, technicians, and educators and offers customized, women’s-only courses and mentoring opportunities with professional female instructors. Click Here to learn more about our upcoming, online women-only PV class.

Upaya Social Ventures fights extreme poverty from the ground up by building scalable businesses, dignified jobs, and long-term prosperity in the world’s most vulnerable communities. We identify early-stage businesses in India with the greatest potential for job creation in the most vulnerable communities. Through our investments and accelerator program, we partner with early-stage entrepreneurs to grow their businesses and create jobs that lift families out of extreme poverty. Our vision is for everyone to have the opportunity to earn a dignified living and pursue their dreams. We believe in a hand-up, not a hand-out, and that access to sustainable, dignified jobs can be the bridge from poverty to prosperity.

West African Vocational Schools (WAVS)

West African Vocational Schools is a Christian skills development organization that trains and equips youth in one of the least developed regions in the world. Each year, WAVS training centers prepare more than 200 youths for work so that they can earn a livable income and provide for their families for the rest of their lives.

World Concern prioritizes economic empowerment of families and economic development in communities we serve through diversified livelihoods, village savings groups, microfinance, vocational training for youth and adults, education, rice banks, and farmer groups.

A respected leader in Savings and Loans for Transformation (SALT) programs, World Concern improves the lives of thousands of women and men who are trained in money management and entrepreneurship through SALT groups. These groups enable members to save and borrow for business or family needs, which are repaid with interest and add to the group’s account balance.

Stable income means parents can give their children the proper nutrition they need to thrive, provide medicine when they are sick, and send them to school. Entire communities thrive when families are financially secure and able to give back.

As COVID-19 continues to ravage poor communities, World Concern has seen that members of savings groups show greater economic resilience and ability to cope with hardships than those who are not members. Instead of selling their assets to survive, SALT members have been using their savings to buy food and pay for medical expenses. Others have borrowed money to start innovative income generating activities.

To learn more, please visit https://worldconcern.org/what-we-do/economic-empowerment/

Organization Profile

Spreeha – Organization Spotlight

By Joanne Lu

Photo credit Spreeha. Students receive computer training.

Spreeha. It means “zeal” in Bengali – a fitting name for an organization that was born out of a passion to break the cycle of poverty in Bangladesh and beyond. Over the last decade and more, it’s been a long journey for Spreeha, listening and adapting to needs as they arise, and culminating with the unprecedented challenges of COVID-19.

Spreeha’s founder, Tazin Shahid, grew up in Dhaka, witnessing extreme poverty first-hand in the city’s many slums. When he ended up working at Microsoft, he decided he wanted to give back to his hometown. It was in one of the slums that he used to walk by everyday where he opened his first mobile health clinic.

At first, it was just Shahid and his friends who supported the clinic, but Shahid wanted to scale up. In 2012, Spreeha Foundation was officially launched in Seattle, followed shortly by Spreeha Bangladesh to implement a global program in accordance with the Bangladesh government’s rules and regulations, and in partnership with other local organizations.

Today, Spreeha Foundation has three U.S. chapters, in Seattle, Boston, and Dallas that are responsible for raising support for the program in Bangladesh as well as helping local underserved communities. Meanwhile, in Bangladesh, what started out as a health-care program now spans the cycle of poverty, with education interventions, job and life skills training, and support for economic opportunities.

As Spreeha’s CEO Ferdouse Oneza explains it, Spreeha has identified the key points in people’s lives where intervention is most effective. When a mother is pregnant and a child is born, their immediate needs are health care. Then, that child is in need of education – which is why Spreeha offers preschool and after-school programs for children. As children get older and become adults, they’re in need of skills training. These skills include leadership training for women and girls to advocate for their rights, computer skills and other life skills for young people to advance in school and work, as well as vocational skills.

“Our vision has been to empower people to break out of the cycle of poverty,” says Oneza. “We learned while working, but we also took time to deconstruct the problem to identify the root causes of poverty.”

Spreeha still operates one health center in a geographic area with 25,000 households, but their telehealth services reach three additional remote areas. In addition, their multi-use community resource center is home to their preschool and after-school programs and many training programs. There are also 15 schools through which Spreeha runs their leadership programs. Spreeha trains the teachers, and the teachers in turn guide the students.

Photo credit Spreeha. Telehealth.

One aspect of Spreeha’s after-school program is helping kids dream about what they want to become one day. These are kids whose everyday realities are entrenched in poverty and whose parents are daily wage earners. Last year, two students from the Spreeha community graduated from university. And this year, another student was admitted into medical school. This is exactly what Spreeha means when they say they’re empowering people to break out of a cycle of poverty.

Economic opportunities are the newest component of Spreeha’s programming, added just a few years ago. Since their inception, Spreeha has created jobs for local community members by hiring them as community health workers. But they wanted to go beyond that and help place people in jobs. So, based on a list of training sectors identified by the government of Bangladesh and the U.N. Development Programme as sectors with job growth, Spreeha began to support vocational training through scholarships and apprenticeships. Some of these sectors include baking, sewing, mechanical repairs. Spreeha’s computer training center, in particular, has drawn enough people that Spreeha could start charging a small fee to make the operation of the center self-sustaining.

Then, the pandemic hit. According to Oneza, 70 percent of the members of the community where Spreeha works lost their jobs. Most of them were daily wage earners, like household workers, rickshaw pullers and construction workers. Malnutrition among children increased 18 percent. More young girls were suddenly sent into early marriages. The effect was devastating.

Photo credit Spreeha. Bring School to Home program.

But Spreeha listened, watched and adapted – as they always have. They began emergency food distribution and partnered with other organizations to deliver nutrition supplements to children in the community. They also piggy-backed off the door-to-door community health services they already had and expanded that system to create a program called Bring School to Home. Teachers delivered school supplies and materials to the homes of students to keep them engaged. Doing so decreased the chances of parents sending their kids to work and never returning them to school.

Similarly, some of the life skills training for girls and adults were continued through door-to-door services in slum communities, while in more remote areas, Spreeha partnered with local organizations to conduct training outdoors.

Photo credit Spreeha. Outdoor training.

Prior to the pandemic, Spreeha already had a telehealth network, so they have leaned into that even more. And as schools have begun to reopen, Spreeha has also resumed its leadership training programs for teachers online.

In a way, Spreeha’s reliance on technology during the pandemic to deliver some of their essential services has actually helped them scale up during a crisis that forced many organizations to shut down. Thankfully, Oneza says, they’ve also been able to sustain all of their employees, many of whom are community members.

There’s also been a shift in employment opportunities in the community. Some seasonal jobs like pulling rickshaws will never go away, says Oneza. But she’s seen young people turn toward more skilled jobs and apprenticeships, like motorcycle or bicycle repairs or even cell phone repairs. And even though Spreeha had to temporarily close their sewing training center during the pandemic, Oneza says many of the women were able to start their own sewing businesses in the meantime.

The resilience of these community members and Spreeha’s own resilience over the last year and half have inspired the organization to keep growing, even beyond Bangladesh.

“The pandemic has shown us that we don’t have to sit back,” says Oneza. “We can innovate. We have been adaptive, and we have seen what can happen.”

Photo credit Spreeha.

Goalmaker

New Mercy Corps CEO Takes the Helm as Covid-19 Makes the Organization’s Mission “More Urgent Than Ever”

By Tyler LePard

Tjada D’Oyen McKenna, Chief Executive Officer of Mercy Corps, has worked with farmers in Africa and with world leaders like President Barack Obama and Bill and Melinda Gates. She has grounded her career in the simple belief that, no matter where someone is born, no matter where they live, they should be able to lead a thriving and successful life.

Tjada D’Oyen McKenna, Chief Executive Officer of Mercy Corps, has worked with farmers in Africa and with world leaders like President Barack Obama and Bill and Melinda Gates. She has grounded her career in the simple belief that, no matter where someone is born, no matter where they live, they should be able to lead a thriving and successful life.

Tjada grew up in Washington, D.C., and Stamford, Connecticut—“very much a mid-Atlantic Northeast gal.” Her parents came of age during the civil rights movement; they surrounded Tjada with Black history and raised her as part of the Black American community. Tjada’s parents taught her that what she did reflected on her community and that Tjada should work for the betterment of her community. Tjada knew from an early age that her ancestors had come to this country as enslaved people and that many people had fought for the progress that has enabled her to be where she is today.

Tjada took those values to heart and expanded her community to encompass the global diaspora and people everywhere who are suffering.

“I think I’m where I was always meant to be, but I didn’t know the contours of how I’d get here or what I’d be doing … I always felt the draw to Africa and felt the desire to give back … I knew I liked leading people. I knew I wanted to have a career that had a positive impact in people’s lives. I knew I liked the ideas behind business and how things worked. I knew I had a deep affinity for giving other people opportunities just as so many other people had paved the way for me to have the life that I have.”

Skills for social good

Her career path is impressive—she went to Harvard for college and graduate school. Tjada earned an MBA with the intention that she could apply those skills to social good at some point in her career. The organizations where Tjada thrived have all had strong shared values and a sense of cultural identity, they gave her room to learn, and allowed her to serve the greater good.

Tjada’s early career was really about learning. As an analyst for McKinsey & Company, she learned problem-solving skills. When she went to work for one of her clients in agribusiness, she learned how to mix business with social good. After business school, Tjada worked for American Express and General Electric, learning general management and how to get things done in large organizations.

Tjada’s work in agribusiness, working in Africa with smallholder farmers, was a dream job, but she didn’t think she had a future there. So when she woke up one morning listening to NPR and heard about the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s investment in the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), it was a pivotal moment. She thought: “That’s exactly what I was doing in agribusiness, but Gates actually has the mandate and the funds to go make huge investments there.” She flew to Seattle for interviews two weeks later and was hired before she left the building.

“I took a huge leap of faith, and I loved every minute of it. And I’ve loved every minute since.”

Tjada spent more than a decade working to end world hunger in roles with the Gates Foundation and then with the U.S. Agency for International Development. She set up and ran Feed the Future, President Obama’s signature global hunger and food security initiative. That was a great complement to Tjada’s earlier work in agribusiness and she learned how to work with really diverse groups of people and how to motivate people without authority. “That was the most transformational experience in my career.”

Tjada’s work on food security ties in strongly with SDG 1 (ending poverty) and SDG 8 (sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all). Her entry to that sector was the result of her corporate work—thinking about markets and how to help other people to self-actualize. The freedom to be economically mobile is so important because economic needs underpin so much of people’s lives.

“I have always seen myself as looking for sustainable solutions and environments where people can make a living and thrive—really self-actualize, really pursue what they’re meant to do.”

“The most vulnerable first”

She was the Chief Operating Officer for Habitat for Humanity and then for CARE, and in October of 2020, Tjada became the CEO of Mercy Corps, an iconic international nonprofit organization. Mercy Corps, headquartered in Portland, Oregon, has a global team of 5,600 humanitarians working in more than 40 countries to alleviate suffering, poverty, and oppression by helping people build secure, productive and just communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic has only heightened Mercy Corps’ beliefs in sustainable economic growth, markets, and systems. It has made their work more urgent than ever. But their focus on resilience—giving people the tools to self-actualize and bounce back from terrible situations—has been helpful in an ever-changing environment. COVID-19 has been the ultimate resilience test for everybody. Mercy Corps staff had to figure out how to keep working in the community while staying safe and making sure the people they work with are safe. They had to shift to digital tools in markets where that wasn’t always easy.

The World Bank is predicting that the number of people who live in extreme poverty is going up because of COVID-19. “A lot of people have lost the gains we’ve spent the last 15-20 years developing. The vulnerable groups who are served by Mercy Corps are especially impacted.” Mercy Corps works in many fragile environments that have been deeply affected by climate change, conflict, and, now, COVID-19. “Any shock makes the competition for resources greater and leads to more people being disaffected. COVID exacerbates everything. Hunger is worse because people can’t buy supplies. The global food chain is disrupted. The global community needs to think about the whole system, not just getting shots in people’s arms.”

“What we’ve seen, in the U.S. too, is that COVID takes every inequity you have in society and makes it worse. We have to structure vaccine outreach, information, and dissemination to be applicable in an inequitable place. You have to reach out for the most vulnerable first. You have to think about the communities that are most remote and hardest to reach … People who are left behind in their communities are even more left behind in emergencies. And with COVID, you can’t afford to leave anyone behind … None of us are safe until all of us are safe.”

Tjada’s team is doubling down on helping people build resilience and come together with their communities in order to thrive. They are focused on how to improve social cohesion, which refers to the strength of relationships and sense of solidarity among members of a community. Mercy Corp is figuring out how to give people access to opportunities digitally and to help keep their communities cohesive and strong.

Mercy Corps has many projects that address digital innovation, unemployment and social cohesion:

- In Ethiopia there was a spike in unemployment for domestic workers so Mercy Corps partnered with a mobile app that matched domestic workers to jobs.

- In Northern Nigeria, Mercy Corp developed a tool to track COVID-19 rumorsand then used volunteer “truth champions” to correct misinformation.

- MicroMentor is an online platform Mercy Corps created to connect promising entrepreneurs with experienced business mentors; they created a COVID-19 Mentor Task Force and recruited mentors with experience dealing with severe economic downturn and post-disaster recovery.

- Youth Impact Labs worked with 29 partners to create more than 8,000 work opportunities for youth in Kenya and Jordan. During the pandemic, Mercy Corps pivoted to provide working capital to participants to help navigate the crisis, technical assistance to grantees, and cash transfers to people to help stimulate local economies.

- Mercy Corps has a digital program called AgriFin that helps smallholder farmers access bundled digital products like market data, financial services and information about pests and where to get quality inputs. They adapted AgriFin to help 16 million farmers adapt to the shock of COVID-19 and even developed a new citizen reporting tool to help warn farmers where the desert locusts were when the largest desert locust invasion in decades threatened farmers in East Africa.

During the pandemic, Mercy Corps has pivoted and tailored many of their existing programs to meet the moment, but there have also been great opportunities to bring new partners or new platforms together to serve people.

A global citizen “trying to do the best I can”

Now that we’ve all been living through a global pandemic that has been hard for everyone, Tjada hopes that more people will feel connected to others around the world.

“The American people have now suffered this big shock. We’ve seen food lines here and we’ve seen unemployment worse than before. If there is a bright spot to come out of COVID, my hope is that we will feel more connected to other countries who are facing the same things we are and who don’t have the resources we have.”

Tjada loves that Mercy Corps is a Global Washington member and part of the Northwest ecosystem of major actors that are having a big impact in the world. She is a humble and conscious global citizen who is proud of who she is and what she’s achieved.

“I’m proud to be the CEO of Mercy Corps. I’m especially proud to be one of the few Black women to be the CEO of an INGO, and as a mother of two young children. I want to expand people’s imagination of what a CEO can look like, where they can come from, and what stage of life they need to be at. I’m hoping to attract more people from diverse backgrounds into this space. I hope people like me in positions like this won’t be rare. I feel really privileged to be able to do the work I do … I’m just focused on helping Mercy Corps have the strongest impact we can for the most people.”

Member Events

September 24- 26: The Max Foundation: Max-A-Thon

September 25: World Concern’s Transform Gala

September 25-26: Spreeha Journey of Hope 2021

September 27: WAC- Beyond the Border: U.S.-Mexico Relations

September 30: Schools for Salone’s Change a Child’s Story Live Auction Gala

October 1- October 31: Take Heart You Are Not Alone Billboard Fundraising Campaign

October 2: Friend’s of WPC Nepal: 11th Annual Hope for Freedom Gala

October 2: 2021 Virtual Gala: The Rose International Fund for Children

October 7: WFF: 6th Annual Evening to Restore Dignity

October 8: TALK: A Conversation with Congressman Adam Smith on China

October 8: WAVS: Dine & Discover West Africa

October 9: Mission Africa’s 15 Year Fundraiser

October 14: WGHA Global Health Impact Awards

October 25: PeaceTrees’ 26th Anniversary Virtual Celebration

Career Center

Accounting Officer // Global Partnerships

Individual Giving Manager // Days for Girls

Check out the GlobalWA Job Board for the latest openings.

GlobalWA Events

October 5: Q3 Final Mile – Impact through Partnerships: Emergency Response to the 2021 Haiti Earthquake